Skyline Gardens doesn’t look like a garden, nor does it look like several gardens. At first pass it looks like a trail you might not be allowed on, a cut though the chaparral behind a fence bedecked with forbidding signs. A few steps further and it becomes a beautiful but typical piece of East Bay ridgeline open space, affording sweeping views of Mount Diablo towering over the inland exurbs. Stay a little longer and it reveals a lost world of California nativity, a refuge where stilt bugs lurk on tarweeds, fairy moths lilt above oceanspray, and whip snakes thread between fringepods.

But it only looks like this because people made it so, and that’s what makes it a garden.

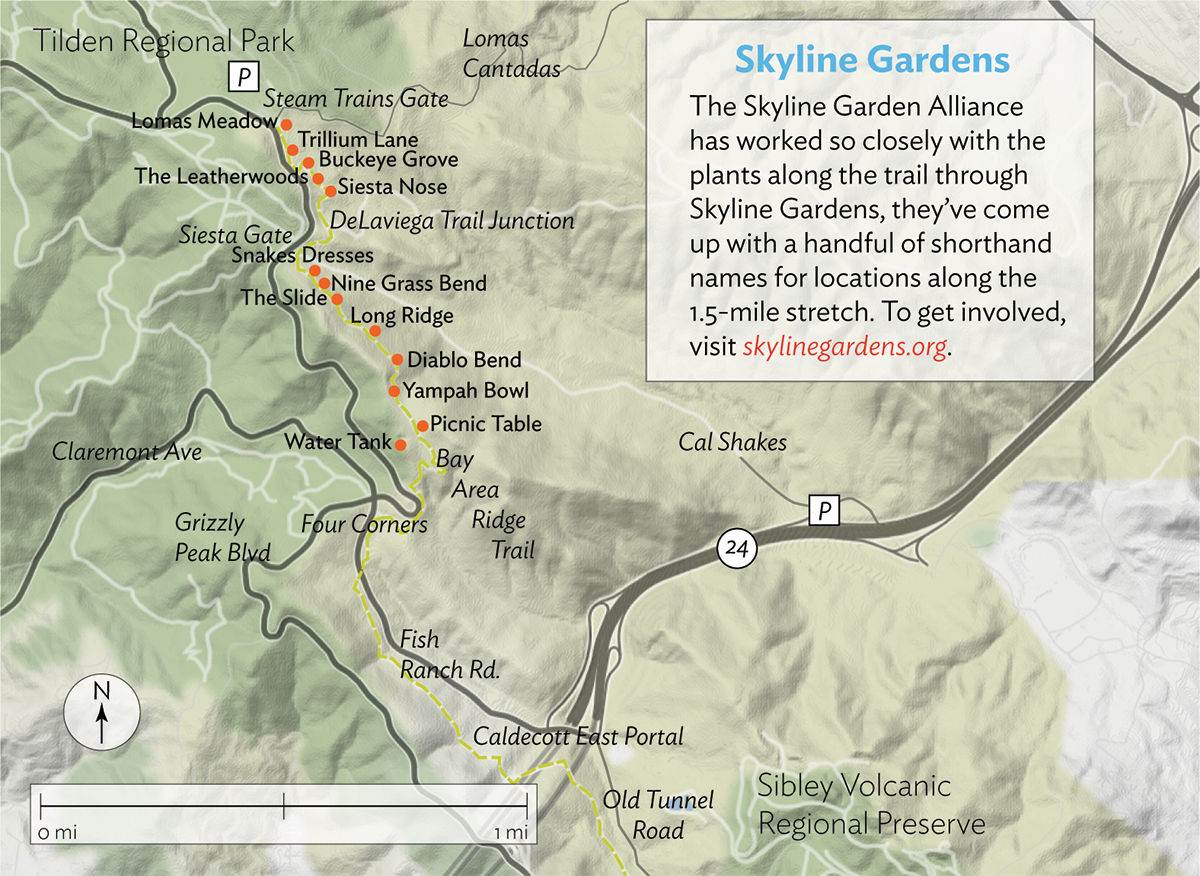

Skyline Gardens is one-and-a-half miles of trail running south from the steam trains at Tilden Regional Park down through Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve to Highway 24. The East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD) manages this watershed land, which drains into San Pablo Reservoir to the northeast. The trail is both part of the East Bay Skyline National Recreation Trail and the Bay Area Ridge Trail. On maps it can look like connective tissue between two more familiar parks. It doesn’t seem like a destination, but as with so many in-between places, there’s actually a great deal to see.

The trail through this area boasts more species of native plants than almost any other public trail of equivalent length in the East Bay (more than 280 and counting), on par with hot spots like the Fire Interpretive Trail at the summit of Mount Diablo. However, it also hosts a great abundance of introduced species, mostly European plants that arrived with European people and have since crowded many Californian species to the point of vanishing.

The fact they haven’t vanished is due in part to the Skyline Gardens Alliance, a volunteer project of the East Bay chapter of the California Native Plant Society that has worked with EBMUD since 2016 to restore the native vegetation in the area and foster the kind of biodiversity it now boasts. Most of those volunteers would credit their progress to Glen Schneider, a naturalist, enthusiast, and unsuccessfully retired gardener. With his worn work pants and aw-shucks demeanor, leaning on his trenching shovel as he launches into one of his endless supply of historical tidbits before stopping midsentence to point out a tiny, germinating lupine, Glen is a gardener through and through, having worked in the nursery and landscaping trade for most of his professional life.

I met Glen on a walk at Skyline a few years ago, and I quickly appreciated what he saw in it and the reason the Alliance has been trying to understand and sustain as much of the natural history and biodiversity of the area as it can. While carefully navigating a gauntlet of poison oak on a subsequent visit, I paused to look beneath the reaching stems of my old frenemy and beheld a carpet of zinfandel-red giant trillium, a finer bloom than I’d seen before or since. Later in the season an even rarer plant had replaced the trilliums: California skullcap, a rare, delicate, ankle-high creature with white flowers resembling snapdragons.

Skyline told me this story of botanical surprise again and again: cobwebby thistles on hot rocky ridges, subtle shade phacelias in umbrous alcoves, a corner where shining white popcorn flowers and orange poppies seem to spill off the trail, guiding the eye east toward Mount Diablo. So many of these “discoveries” were all the more unusual for their Diablan affinities; plants like the cobwebby thistle, fringepods, and chia are common in the well-drained soils and arid conditions of the interior Coast Ranges but infrequently encountered in the oak-and-bay forests and coastal chaparral of the East Bay Hills. What were they doing here?

Unlike Mount Diablo, the rocks undergirding Skyline’s part of the East Bay Hills are largely volcanic, former lava flows over alluvial gravels that were bent upward by tectonic action to form hard, steep ridges that, despite the rich volcanic soils, were too steep for European farming and were probably never plowed (though they were and still are grazed). Rocky outcrops with southern exposure get baked in the summer heat, but the area also receives abundant winter rain and summer fog, creating an environment of extremes not unlike the summit of Mount Diablo.

That helps explain the diversity of the site as a whole, but often not why you see a specific plant in a specific spot. For that, you may have to turn to the site’s recent human history. Glen started visiting the area in 1992, when he and his 11-year-old daughter decided they would walk from their home in Berkeley to his parents’ place in Lafayette. During the 20-plus-mile adventure they were impressed by the number of wildflowers, and thus the walk “became a family tradition,” he says. They would keep lists of the kinds of flowers they saw (“we got 75 species one day!”), but they also noticed the encroachment of introduced plants: “The trail on both sides was Italian thistle up to my knees.” On a subsequent visit in 1995, he decided he would just try to pull a few that were crowding out a patch of shooting stars along the trail. A year later, he says, “I came back and I noticed, ‘Well God, there was only about 10 percent regrowth,’ and I started plucking those out, and the next year they were all gone! So I just picked away at it for over 20 years, and occasionally I’d bring friends up and we just picked the thistles. And I thought, ‘Wow, this is really great.’” Liberal use of “wows” and the assumption that pulling spiny four-foot weeds might inspire your friends to do anything but edge slowly toward the nearest exit are both, well, typical Glen.

Around spring of 2016, Glen and his friends and family were seeing the results of their guerrilla weeding: introduced species were receding and native wildflowers were blossoming. One day they encountered an EBMUD ranger who seemed more curious than concerned, so Glen asked if EBMUD might officially sanction their efforts. EBMUD not only granted permission but agreed to furnish them with supplies, and Glen and his band of merry gardeners have been snipping thistles and plucking spurge ever since as the Skyline Gardens Alliance (they refer to themselves as “Skyliners”).

Which brings us back to the often-complicated reasons certain plants occur where they do along the trail. The Skyliners follow what is known as the Bradley method, a form of ecological restoration that calls for removal or suppression of exotic species (let’s call it weeding) in areas where high concentrations of native species persist, with minimal planting from local seed stock. In principle, places where native plants remain are where they stand the best chance of recovery, and native plants on site are the species best adapted to local conditions and need only a leg up against the aggressive weedy competition to spread outward. At Skyline, weeding includes lopping off Italian and bull thistles with pole-mounted hand-sickles before those plants go to seed, hand-pulling smaller species like spurge, and, for broad areas, spraying a thin layer of vinegar, an effective, otherwise harmless topical herbicide to use on annual plants. This weeding drives much of the native plant abundance at Skyline: when introduced species were cut back, native species often grew in their place. They had been there all along.

However, in select areas, the volunteers have also collected seeds of rare and unusual plants growing off-trail at Skyline Gardens, germinated and reared them under nursery conditions, and replanted them close to where the seeds were collected to help secure their populations, or in other parts of the site that seem like appropriate habitat. As Glen says, “The vote of confidence is if it seeds and you get a next generation,” and a next, and a next.

That’s a long way of saying that if you see some chia along the trail, it might be there because its ancestors have grown there for millennia…or it might be there because volunteers established it there in the last few years. And I have to admit, this troubles me. I like to think of myself as a naturalist: I observe nature in an effort to understand it. To me, “nature” is the part of the universe beyond human dominion. If that chia was there because it evolved there, or 10,000 years ago a well-heeled woodrat happened to carry a seed there and its descendants have been holding on ever since, that seems beyond human dominion to me. But if Glen planted it there two years ago, that is a human act, a very recent human act, and it tells me more about the kinds of people who prefer to hang out on this trail than about the kinds of plants with the same preference. I do not walk in the woods to see humanity’s work. That’s what gardens are for.

And apparently, I am not alone in that feeling. At least one person complained to EBMUD about Skyline volunteers planting baby blue eyes on the site, claiming that the species didn’t occur in the area and thus was not appropriate in a restoration project. Despite the fact that baby blue eyes occur in numerous locations in the East Bay Hills, including the Skyline Gardens area, a part of me is on that guy’s side when it comes to these intentional plantings. I think I’m looking at the result of a natural process, and then I feel cheated when I realize it was human will instead. The Skyliners have done such a good job with their planting that I often can’t tell what they planted and what they didn’t … which is part of my problem.

This tension between natural processes and human intent underlies a fundamental question about how we view the world: what is “nature,” anyway? Aren’t people a part of nature? If they are, what’s the difference between a garden and a wilderness? You can trace this line of thought back to Thoreau’s bean patch if not to the Old Testament, but my mind often turns to an inflammatory essay from 2012 by scientists Michelle Marvier, Peter Kareiva, and science writer Robert Lalasz titled “Conservation in the Anthropocene: Beyond Solitude and Fragility.” They argued for the necessity of abandoning our obsession with pristine nature where a person is “a visitor who does not remain” and embracing the need for human activity on the landscape, activity that might modify but not destroy it. They stressed that people who seek to use the land must be addressed, not ignored, if they are to become partners in its conservation. They wrote that “conservationists will have to jettison their idealized notions of nature, parks, and wilderness—ideas that have never been supported by good conservation science—and forge a more optimistic, human-friendly vision.”

And boy, did “traditional” conservationists let them have it. Eminent biologists like Michael Soule and E.O. Wilson lambasted the authors for being corporate shills and bad scientists. Soule dismissed them as “gardeners,” presumably happy to let their children play on a manicured lawn when they should be running through the woods. It was all very heated. Marvier and company said many things I don’t agree with, but the crux, that there’s a lot of land between the parking lot and the sacred grove that we have to make decisions about and that doing so requires us to see human intervention as an integral part of ecosystems, rings in my head whenever I walk the trail at Skyline Gardens. Because it is a garden. The signs of human influence are everywhere, in obviously weeded areas, in cuts for a firebreak, in the very existence of park infrastructure like benches, signs, and the trail itself. It’s also not pristine: Eurasian annuals are still very much a part of the landscape, as are the Tasmanian blue gums that tower over most of the area (and the traffic helicopters that hover over them). And yet at Skyline, people have intervened not just to make something beautiful, or even something peaceful, but to ensure that the other species who preceded us and survived our arrival are approached, assisted, and collaborated with as we encounter the future together. Is it so wrong to be this kind of gardener?

We should also consider not just what preceded us at this place, but who, and how they acted upon the land. While there are no known archaeological sites at Skyline, Ohlone people almost certainly walked the area before their decimation by European settlers, and, as M. Kat Anderson wrote in her book Tending the Wild, we know they “encouraged desired characteristics of individual plants, increased populations of useful plants, and altered the structures and compositions of plant communities.” That is to say, they were gardeners (and still are today). Did Ohlone elders plant the native bulbs that flowered when the Skyliners cut back the European thistles? Is the Skyline Gardens Alliance trying to restore the local ecosystem to what was, in essence, a gardened state? If the chia I see was planted not by Glen two years ago but by Ohlone gardeners 300 or 1,000 years ago, is it still a wild flower, and if not, when will it be?

Journalist Emma Marris has written eloquently on the topic of intervening in wilderness, and in an essay in Orion, she wrote, “If we truly are the humble beings we strive to be, if we truly feel we are not more valuable than other species, then we must be willing to sacrifice our human-made category of ‘wild’ for the betterment of those beings.” I read this to Glen as we sat on a bench in a spot the Skyliners call “Siesta Nose,” an exposed bit of ridge looking down on vibrant oaken hills, festooned with newly sprouting blue dicks and hill suncups benefiting from the weeding. As he considered Marris’s words, I asked Glen, an avowed lover of wilderness and admirer of Muir, who indeed chose the name Skyline Gardens after Muir’s affection for the latter word in describing sublime high Sierran meadows, how he would feel if he encountered a new species on the trail only to discover some other gardener had put it there, to realize what he thought was wild was not. He looked at me for a moment, and exclaimed with a smile, “Great! As long as it’s local seed, time will sort it all out.”

One of the great advantages of this wilderness that is a garden (or is it a garden that is a wilderness?) is that if my mind overfills with conflicting thoughts about what is and isn’t natural, I can empty it by joining the Skyliners and weeding. As Glen puts it, “When I’m out weeding, I’m just weeding. I’m not thinking about anything else.” And indeed, few acts are as self-effacing as sticking your face in the dirt to watch how much happens on a hand’s breadth of earth. Gardening days with the Skyline Alliance often start with some simple natural history: a walk around the work area to see what’s germinating, what’s blooming, what’s that plant? Oh, it’s this? Did you ever notice this weird leaf shape here? What’s that about? On a recent Sunday morning, we began the day by counting how many different plants we could spot in our small area, a communal act that revealed what plants we were interested in, which we knew, and which we didn’t. Even while we pulled introduced annual grasses, there was always time for curiosity (I became particularly enamored of a tiny millipede), to say nothing of chitchat (what friends were up to, maybe a corny joke or three). I’ve volunteered at Skyline several times, but most days follow a similar pattern of camaraderie and mutual learning, a deep and abiding love of snacks and sharing said snacks, seeing the world more intimately but also seeing yourself and your fellows in it, very physically engaged in working toward a particular hope for the future.

And my hope for the future may be what Glen and his compatriots have changed my mind about the most. When I first started visiting, I have to admit I viewed their efforts as futile, trying to re-create an imagined precolonial past that could not survive a single season without maintenance, let alone indefinitely. How sad would it be if people were still pulling weeds here in a hundred years? But now I think I had it wrong: if people and plants are still working together to carry a piece of California’s heritage into the future in a hundred years, that would mean the gardeners at Skyline planted seeds of their own, seeds of the culture they are fostering, a culture of snacks and jokes, but also a culture of getting out and doing something every week, of meeting our peer species at ground level and learning how to grow old together. It would, I now believe, be a triumph.