Leading a tour of the San Vicente Redwoods, Nadia Hamey hops up onto a four-foot-diameter redwood stump surrounded by other tall trees.

“I didn’t know you were logging trees this big,” I say.

The forest is shady, quiet, and spacious. Hamey sweeps away the fresh red sawdust with her hands and counts more than 100 rings. “This is a crop-size tree,” she says. “Cutting it releases the smaller trees so they can eventually be harvested, too.”

The two organizations that own this property are conservation leaders here in the Santa Cruz Mountains some 50 miles south of San Francisco. And—contradictory as it may seem—they are logging California’s most iconic tree, not for profit, but as part of a long-term rescue strategy for the region’s redwood forests.

According to the nonprofit Save the Redwoods League, only 120,000 acres of unlogged, or “old-growth,” redwood forests are left in the world, mostly ensconced in local, state, and national parks in northern California. That’s an area a little larger than the city of San Jose. But the state also has 1.5 million acres of forest in which almost all the redwoods have been logged at least once. (About 300,000 of those acres are in the Bay Area and Santa Cruz County.) Those forests are a new frontier for redwood conservation organizations, which up to now have mostly focused on saving the old-growth forests.

In 2011 two local conservation organizations, Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST) and Sempervirens Fund, purchased San Vicente, one of California’s “working” redwood forests and also the largest remaining block of privately owned forest in the Santa Cruz Mountains. After several years of planning, they’ve now begun carefully felling some of the medium-size redwoods on one part of the property to finance an innovative restoration and preservation plan on the rest. Eventually, POST and Sempervirens spokespeople say, more than half of San Vicente could look and function like an old-growth forest, with dead trees, natural openings, plenty of healthy, hulking redwoods, and complex layers of plant and animal life—everything from trillium to Townsend’s bats.

This is forest conservation 2.0—a plan for the rest of the redwoods.

A Major Conservation Target

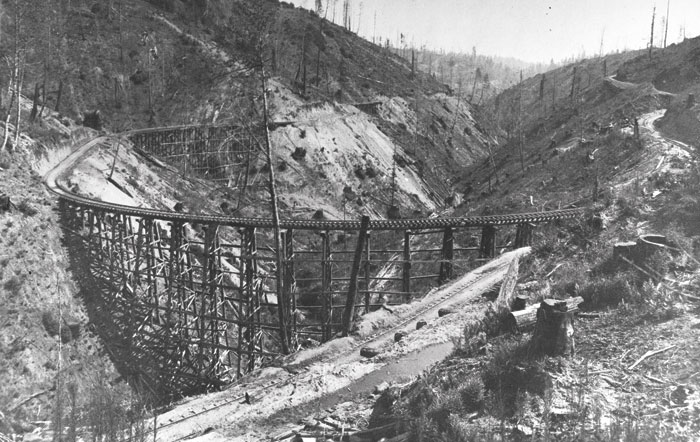

San Vicente’s 8,532 acres have been producing logs and limestone since the early 20th century. Some of the logs were used to rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. The limestone was used for making cement. By the 1920s, most of the best redwoods—some more than 250 feet tall—had been hauled away. But logging resumed in the 1950s and continued as a secondary source of income for a succession of cement company owners. Today, the property is crisscrossed by 72 miles of dirt roads. There’s a former train station deep in the forest with tunnels blown out of rock. The deep canyon created by a huge limestone quarry has never been reclaimed.

Yet despite these scars, San Vicente is still biologically rich and wild. Facing the Pacific Ocean, it’s a vast, well-watered chunk of coast that contains, in addition to recovering coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens), a field guide’s worth of wildflowers, shrubs, and other trees. Mountain lions, peregrine falcons, and coho salmon are hanging on here, along with some 90 ancient trees that were spared the axe because of remoteness or oddities in their wood.

For years, the threat of McMansions and other development had loomed dangerously close to this property. And for years, conservationists have eyed it for its natural values and as a big chunk of a grander vision: what Sempervirens Fund calls the Great Park, a 125,000-acre expanse of redwood-dominated forest that stretches from Silicon Valley west to the Pacific Ocean and from La Honda south to Santa Cruz.

Shortly after the 2008 recession, POST and Sempervirens raised $30 million to purchase the property from the multinational building materials company CEMEX. In the old days, they might have closed the deal and handed their prize over to the state parks department. But these days the state doesn’t have the capacity to take on new parks. So the two land trusts realized that they would have to hold and manage the land themselves and that they would have to do it together: It’s simply too big a lift for just one organization. If they should ever sell, a conservation easement purchased for $10 million by Save the Redwoods League—a critical part of the complex multiparty deal to acquire the property—ensures that San Vicente will remain undeveloped forever.

“Humans came in and messed things up,” says Sempervirens land conservation director Laura McLendon. “We want to come in and repair the damage.”

The Forest Steward

It’s one thing to say you’re going to sustainably manage a property. It’s another to actually get out on the ground and do it. Enter forester Nadia Hamey. An ecological thinker who cares about fish and flowers as much as trees, she knows these woods like no one else. She’s planned and executed timber cuts on this property since 2008, made hard-hatted descents into its mine shafts and limestone karst caves, led field trips for botanists, and taken researchers out to listen for marbled murrelets.

Pulling up invasive plants as we walk, Hamey describes her evolution from outdoorsy kid to conservation-minded forester. She grew up in British Columbia, where her father was a forester and her mother a habitat protection officer. Near her home on Vancouver Island, she saw ancient forest clear-cuts that extended from ridgelines to the sea. “I couldn’t agree with those practices,” she says.

So she left home to study forestry at the University of California at Berkeley with the goal of learning how to manage forests more sustainably. After school, a stint at the university’s research forest, and a couple of timber company jobs farther north, she moved to Santa Cruz County in 2006. There, working for the Forest Stewardship Council–certified Big Creek Lumber Company, she found “a different attitude about how logging should be conducted.”

Today she’s an independent forester, working on several properties in the region including as property manager at San Vicente. She shows me a thick white binder, two years in the making, that describes the plans developed by POST, Sempervirens, and Save the Redwoods. They’ve divided San Vicente’s 8,500 acres into three categories: “preservation reserves” (11 percent),“working forest” (43 percent), and “restoration reserves” (46 percent). They’ll leave the preservation reserves alone, except for maintenance work like weed control and shoring up roads and culverts. In the working forest, they’ll do extremely careful commercial logging. And in the restoration reserves, they’ll try to coax the hodgepodge of species there today into a thriving redwood forest.

I ask if the goal is to create the old-growth forests of the future. “It’s a little lofty to say that,” Hamey says. “But we can put this land on a trajectory to be better habitat sooner.”

Restoration Reserves: Nudging the Forest Back

Our first stop is in one of the restoration reserves, where some of the project’s toughest decisions are being made. We walk down a shaded road littered with chubby tanoak acorns and framed by the trunks of slim second- and third-growth coast redwoods. Generally redwoods don’t need much help from humans. They’re patient. With their tolerance for shade, their resistance to fire, and their long—sometimes over 2,000-year—life spans, they can outcompete every tree around them.

“They can have 500 years packed into one foot in diameter,” Hamey says. “And then, when conditions are right, [they] start growing rapidly. They can have 40 years’ worth of rings per inch and then three years per inch.”

With all the logging and fire suppression this property has endured, however, the redwoods here could use “a nudge,” Hamey says, back toward conditions that prevailed before European settlement. That’s the goal in the nearly 4,000 acres of the property designated as restoration reserves.

How does she know what those pre-colonization conditions were? “Stumps are a good clue,” Hamey says. She shows us an area with huge redwood and Douglas fir stumps that were likely cut in the early 1900s. Today, about 10 to 30 stumps and about 300 live trees—including tanoak, redwoods, Douglas fir, and Coulter pine—populate each acre. Those 300 trees (with trunks ranging from more than two inches to several feet thick) cover an area a little smaller than a football field. Thinning them will help the rest of the forest grow back more vigorously.

Then there’s the question of which species—and which individual trees of those species—will get the axe. Because loggers have preferred redwoods, that once-dominant species has lost its footing on this part of the property to the less commercially valuable tanoak and Coulter pine, a tree that mostly grows in Southern California. Tall, dark-barked Coulter has spiky cones that weigh up to 11 pounds—the heaviest of any pine’s.

As Hamey points out, the Coulters don’t belong here—they were grown, along with nonnative Bishop pine, in a nursery that used to be adjacent to the property. “They are naturally regenerating, which is a bummer,” Hamey says. “So part of the restoration effort has to be to liquidate the Coulter pine.”

Tanoak may take a hit in the restoration reserves as well. It’s a native species with many ecological benefits, but past logging of redwood has left thick “dog-hair” stands of tanoak just above the road. She plans to cut down some of these trees, dabbing a short-lived herbicide on each stump so it doesn’t resprout. She’ll leave some of the carnage in place, providing the forest with more downed wood and (upright) snags. Rotting wood can shelter a Noah’s ark of birds, lizards, salamanders, and other small animals, organisms that are just as much a part of a healthy redwood forest as the trees themselves.

Another way to deal with overgrown thickets is fire. “This is a fire-adapted plant community,” Hamey says. “If you don’t have fires, the redwoods become incredibly choked.”

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) has agreed to ignite prescribed burns at San Vicente when conditions allow. Hamey happily envisions small fires “skunking along the forest floor,” removing small trees and brush. To protect nearby properties, the landowners have established corridors up to 100 feet wide where large trees loom over a more-or-less naked forest floor. These are “shaded fuel breaks” where CAL FIRE could keep a prescribed burn—or a wildfire—within bounds.

Picking the Winners

Even among the redwoods themselves, the new landowners will be making some life-or-death choices. Hamey points to a six-foot-diameter redwood stump surrounded by a dozen smaller trees—clones sprouting from the root crown of the parent tree. She’ll likely reduce the number of trees in this cluster “and pick some winners.”

Winner-picking is wickedly complicated. As redwoods grow, they tend to lose their lower branches. In a crowded forest, almost all the branches with needles—and therefore all the trees’ photosynthetic capacity—are in little tufts at the top. In restoration reserves, Hamey is trying to space redwoods in ways that would make more room for lower branches with needles and speed up the redwoods’ growth.

As she cranes her neck to look upward, she also considers where a logged tree would fall—how it would affect other trees and plants, and whether the forest needs the wood standing or on the ground. She considers the angle of the sun on a tree’s south side. If sun hits the base, the redwood might sprout, worsening the crowding. She likes big trees with broken tops, which can be a good thing for wildlife.

“Redwoods have all kinds of funkiness,” Hamey says. “They have cavities in the middle of the trunk. They have random platforms and reiterated tops. We even think about launching trees into other trees to create some of that. Or blowing up the tops to get a candelabra shape.”

I raise my eyebrows at the thought of blowing up trees. “We haven’t done any of that,” Hamey says with a grin. “But we’re trying to create complexity.” Which, of course, makes her job more complicated. “I can’t do this work for eight hours a day,” Hamey says. “It hurts my neck and fries my brain, because I’m thinking of so many things.”

Restoration forestry has shown promising results in logged-over redwood forests at Del Norte Redwoods State Park in Northern California and in other kinds of forests around the world. But there’s no oops-proof recipe for bringing back a redwood forest here. So for starters they’ll experiment on a small scale—just 50 acres on their first restoration reserve—see what happens, and adjust accordingly. Where they are making indelible decisions among the trees, “we’ll try three or four different intensities and methods,” Hamey says. “We don’t want to put all our eggs in one basket.”

Earlier, I’d asked one of Hamey’s bosses, Sempervirens’ Laura McLendon, if she’s nervous about the weight on her shoulders. Do we really know enough about natural processes to try to improve a redwood forest with herbicides and chain saws? How is this effort different from those of well-intentioned foresters in earlier eras who made a mess of things by promoting wrongheaded theories like fire suppression? “We’re different because we know that we don’t know,” McLendon says. “We want to learn.”

Not everyone agrees that thinning redwoods is a good idea. “It worries me that people are making decisions for the forest,” says ecologist Will Russell of San Jose State University. Fixing roads and controlling invasive species is essential, but redwood thinning is counterproductive, he says: Given enough time, redwoods can thin themselves. “We don’t know which ones are going to become the dominant ones,” Russell adds. “There may be factors we can’t predict: the opening of a gap in the forest later, a change in the availability of resources.”

Russell acknowledges that thinning redwoods will create bigger trees faster. It’s a standard technique used in timber production. “But why is this important? Sometimes small funky trees end up being the most valuable ecologically.”

A member of Sempervirens’ science advisory committee, Russell has studied parks in the Santa Cruz Mountains where redwoods were cut around the same time as at San Vicente. The parks he surveyed reached tree densities equivalent to those in old-growth redwood forests in 80 years or so. The resulting redwoods weren’t as big as the old-growth trees, but their numbers were about the same.

Given the multiple rounds of logging here, San Vicente hasn’t had 80 years to rest. Would it be wiser to stand back and let nature take its course? It depends on what kind of forest you want, says Emily Burns, director of science at Save the Redwoods. “The species composition at San Vicente has really shifted over time, from redwoods to other species. And with the impediments the younger forests are facing today, we don’t think that they’ll recover into the large, old redwoods that we want.”

Does she think speed is important? “I think about species like marbled murrelets,” Burns says. “One of the things they lack is nesting habitat. If we can get more big trees that are suitable for nesting grounds in the next hundred years, it’s worth the investment.”

Working Forest: Logging with a Light Touch

By afternoon we’re in the working forest, the place that helps pay the bills. While the goal on the rest of the property is to move toward old-growth conditions, the goal here is to do no harm—and, of course, to make enough money to fund the project’s restoration and maintenance work.

Standing beside a medium-size redwood, Hamey whips out a wooden ruler called a Biltmore stick to measure the tree’s diameter. She’s looking for what I’ll call a $400 tree: a straight redwood about 120 feet tall and about 30 inches in diameter that would yield about 1,000 board-feet of lumber. At current prices, that tree might be worth $800 or so. Subtracting expenses for planning the harvest; cutting, transporting, and milling the tree; and mitigating damages, the landowners would net about $400 from the sale of that tree.

In the summer of 2015, POST and Sempervirens contracted with Big Creek Lumber to selectively log 10 percent of the working forest. They spared all the oldest trees (some over 200 years old), while felling some hefty 90- to 120-year-old trees with “a light touch”: retaining key wildlife trees, repairing roads and culverts, leaving ecologically useful woody debris, and expanding buffer areas around streams. While removal of up to 7,000 board-feet per acre would be allowed every 15 years under state and local logging regulations, the landowners have chosen to remove less than half that amount—the equivalent of three 30-inch trees per acre.

For a group like Sempervirens, which has been in the business of preserving redwoods for 116 years, this is a revolutionary way of thinking. Cutting the forest in order to save it? “Context is everything,” says Reed Holderman, who was Sempervirens’ executive director at the time the property was purchased in 2011. “At the bottom of the recession we were trying to protect the largest single property in the Santa Cruz Mountains and also find a way to maintain and steward it. How do you make a living, breathing sustainable redwood forest ecosystem? Our strategy is landscape connectivity—connecting critical pieces—so it can sustain itself like it did before most of it was cut down.”

In the land trust business, money for land acquisition is easier to find than money for land management. After raising $30 million to buy the property, “we knew there wasn’t going to be a lot of help from anyone to restore and steward it,” Holderman says. So Sempervirens and POST decided to think about their role in a new way.

“Huge parts of California are managed as industrial forests,” says Paul Ringgold, formerly of POST and now managing the San Vicente conservation easement at Save the Redwoods League. “If and when the companies that own these lands decide they can no longer profit from them, they’re going to put them up for sale. We think the main issue is to secure these lands as forests that will remain forever.”

To a layperson, San Vicente’s working forest doesn’t look much different from the rest of the property, with its tangle of tanoak, some lofty, furrowed Douglas firs, and the occasional stand of medium-size redwoods. As we walk up a road, I ask Hamey how long it will take to reach the site of last summer’s commercial logging. She points to an ordinary-looking copse of redwoods about 50 yards to our right. “We took one tree over there,” and to the left, “one tree over there.” The answer to my question is clear. I may not be able to see the cut, but I’m in it.

Redwoods for the 21st Century

Our tour never made it to the preservation reserves, the most inaccessible and ecologically intact of all San Vicente’s lands. In these watersheds, I’m told, a few big old trees still stand tall, the understory is a little richer in native plants, and if you get up early enough, you might be able to hear the wingbeats of marbled murrelets. The preservation reserves will serve as a benchmark for measuring the success of activities on other parts of the property. They’ll not be subject to any experimentation.

In setting the boundaries of the preservation reserves, “we wanted to figure out where the best growing conditions for redwoods are,” says Emily Burns. “We looked at things like slope, aspect, and moisture. We gave those areas a higher priority for protection.”

Burns hopes the project’s preservation reserves and, in time, the restoration reserves as well will safeguard a version of Sequoia sempervirens that is well adapted to the Santa Cruz Mountains, which are at the drier, southern end of the redwood range. Since the northern end of the redwood range may be drier in the future, thanks to climate change, these redwoods could also prove vital to the survival of redwoods as a species.

Without a doubt, a healthier redwood forest here would be good news. Wildlife would benefit—and humans too. A healthier redwood forest with larger trees would collect more water from fog and boost the region’s water supply. It would suck up more climate-altering CO2 (a task at which redwoods excel due to their enormous volume of wood and long life spans). And it would mean that a key ecosystem in the Bay Area’s suite of habitats would be around for years to come. “And there’s just the human experience of enjoying the larger forests, the old-growth condition,” Burns says. “People love walking under the tall trees.”

Public access and recreation have been part of the plan from the beginning, and an access plan—still in the works—will lay out ground rules and a trail system. The challenge is to find a balance between visitor enjoyment and the project’s logging, stewardship, and research goals.

And indeed, amid all the logging and restoring, POST and Sempervirens are using the property as a scientific laboratory to better understand how a redwood forest works. Well-concealed camera traps are part of a collaboration with the Puma Project at the University of California at Santa Cruz to track mountain lions and study their behavior. In another study, scientists are using acoustic monitors to document the presence of marbled murrelets. And the Western Cave Conservancy has brought in researchers to study life in some of the property’s karst caves.

Thinning skeptic Will Russell will be working on the land as well. With a grant from Save the Redwoods League, he’ll gather data about the prevalence of western white trillium (Trillium ovatum), a flower that tends to show up (along with sword fern, vanilla leaf, violets, and redwood sorrel) in redwood forests that are recovering from logging.

“I’ve seen some trillium on the property in areas of mature second growth,” Russell says, “which is exciting.” Monitoring the species over time, he says, will suggest if any of POST and Semperviren’s interventions are harmful—and which treatments are doing the most good.

Rumbling homeward in her pickup at the end of the day, I ask Hamey, who is 38, if she’s sad she won’t be around to see the long-term effects of her work. “I do see some results,” she says. “But all forest management decisions last way beyond a human lifetime. I love that. I feel a lot of pride to be making these lasting decisions.”