t an impressive 24 inches, the finger feather of a California condor spans Richard Neidhardt’s forearm and then some. There’s an old story, probably folklore, Neidhardt says, that claims the Forty-Niners used to cut the feathers to use as vials for the gold dust they found. As he holds the feather up for a crowded audience at the Mountain View REI, it’s easy to imagine it as a container. What’s harder to imagine is a world in which condor feathers were sufficiently easy to obtain for such a commonplace purpose.

The Central California flock of condors today consists of just 69 birds, says condor tracker Neidhardt: 33 in Pinnacles National Park and 36 in Big Sur. Another few hundred birds are scattered around the southwest, bringing the global population to 437. The numbers are a simultaneous illustration of decline and growth: the once-common California condor was declared extinct in the wild in 1987, and it took 16 years before a condor was released into Pinnacles in 2003, yet from that successful captive breeding program has sprung two Central California flocks that despite being 50 miles apart have started to interbreed. The dramatic decline and tenuous recovery are what have launched Neidhardt, a condor tracker and active volunteer in Pinnacles National Park, on a media blitz of sorts, and put him in front of an enthusiastic audience in Mountain View. The condors need more volunteers and more attention, Neidhardt says, and to try to find both he’ll be speaking at Bay Area REI stores for the next few months, as well as leading guided nature walks through Pinnacles in the fall.

Through their numbers are on the right track, the condor population isn’t self-sustaining. Condors in the wild still face significant threats from lead poisoning and micro trash, and require constant monitoring — most of it by volunteers. The birds are subject to frequent blood tests to determine lead levels, which Neidhardt said became easier for Pinnacles volunteers when the Oakland Zoo started a condor rehabilitation program. Before, volunteers would have to drive to the Los Angeles Zoo with the birds along for the ride, maintaining absolute silence to keep the birds from becoming stressed. Neidhardt once had a bird vomit in his car to start the five-hour drive from L.A. “It took days to get the smell out of the car,” he says.

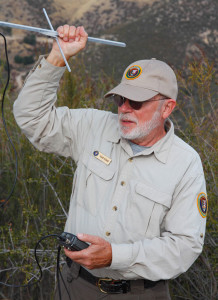

Condors in the Pinnacles are tracked via GPS or radio transmitters, although volunteers generally prefer GPS, since the radio transmitters require standing on tall peaks and trying to maintain line of sight. Both are expensive to implement and maintain, and rely heavily on cooperation between volunteers who work with six full time staff on the condor crew. Neidhardt, who retired from a 40-year career in construction in 2009, has been a volunteer since 2010.

Many of the people listening to Neidhardt in Mountain View had already seen a wild condor. Experience hadn’t dampened their enthusiasm, though, and after his lecture Neidhardt leads a lively question-and-answer session. Relative to other charismatic conservation cases, he says, little about condors is known. One audience member asks how long condors live, and Neidhardt says we don’t know yet; the oldest known bird is 45 and still breeding happily in the Los Angeles Zoo. There are also lots of questions about condor intelligence and personality, and lots of stories of birds as seen from roadside overlooks and Pinnacles trails.

Neidhardt says he made a pilgrimage to Pinnacles after reading about the first condor nest in the park. On an early morning trip, he spotted someone rappelling down a cliff to the nest to replace a condor egg that wasn’t fertile with a captive-bred egg that was ready to hatch. A handful of biologists had their scopes trained on the cliff, and Neidhardt asked them what would happen next. They replied that volunteers would be needed to watch the nest, and Neidhardt says he knew instantly that he wanted to help. Now Neidhardt goes once a month, spending an entire week at the park. “It’s the most gratifying thing I’ve ever done,” he says.

He knows many of the birds by the number assigned to them at birth by biologists, though none is closer to him than the chick whose egg he saw placed in the nest on that first trip, bird 550.

Neidhardt watched 550 fledge, watched her learn to fly in starts and stops, crashing more often than not. Now she’s near sexual maturity, which is around six years old in condors, and has been on the lookout for a mate. “She’s been spending a lot of time on the coast,” he says.

Neidhardt still has something to remember her by, though. He passes around the baby tags that were once on her wings, a gift on the second anniversary of his volunteering. The large numbers form part of the iconic image of the California condor today- soaring on thermals, numbered tags stark on their wings. “The condor is an icon of America,” he says.

Richard Neidhardt will lecture about condors at Bay Area REIs on September 15, 17, 22, 23, 26, 29, and 30, and October 6. Find out more at http://www.pinnaclespartnership.org/

-300x226.jpg)