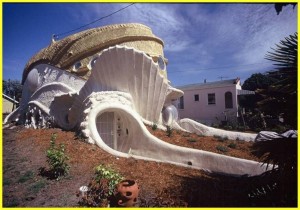

Juxtaposed to the neat rows of traditional, boxy homes, the prehistoric looking “Fish House,” as Berkeley locals call it, is clearly not just any other house. With its spiny fin-like ridges and circular windows, the house’s architect, Eugene Tsui, is not just any other architect.

“We are on a sinking ship,” Tsui told Bay Nature.

Human encroachment on the natural world, global climate change, our vulnerability to natural disaster as a highly complex civilization — these concerns work their way into Tsui’s blueprints as he’s designed a number of unique structures all over the Bay Area and the rest of the world.

The 57-year-old Minneapolis native, who currently takes pen to paper at Mt. Shasta while a permanent office in San Pablo is under construction, takes a different perspective than most architects. For the past 23 years, he has pioneered sustainable architecture, long before it became trendy in the design professions and trademarked under the LEED-certified label.

Tsui, who also designs clothing and furniture, says he turns to nature for inspiration on solving human’s toughest design questions. It turns out, the critters of the world know a thing or two about conserving resources and withstanding disaster.

“The first question I ask myself when I start any project is ‘How would nature design this?’” Tsui said.

Nature’s fortress

When it came to the design of the “Fish House,” or the “Eye of the Sun” as Tsui formally named it, safety was his primary concern. His parents, the future residents of the house, wanted something that would be sturdy enough to hold up in earthquake territory, as well as a “fortress away from the hustle and bustle of life,” Tsui said. Logically, Tsui looked to nature’s arguably most durable creature — the tardigrade.

Tardigrades, or “waterbears,” are 1-millimeter long arthropods that are most often found in moist places like moss and lichen. With four pairs of legs and chubby, ovular bodies, the little animals are virtually indestructible. Tardigrades can withstand temperatures ranging from nearly absolute zero to above the boiling point of water, and can hold up against massive doses of radiation, over a century without food or water, and even the vacuum of space. You could argue that they’ll be the last organism on Earth if all goes to hell in hand basket.

Tsui extensively studied tardigrades (even consulting with Harvard biologists about the organism) and noticed several features that make it particularly hardy. It has no hard edges or angles, allowing it to diffuse external stress easily throughout the body and lessen impact from damage.

Similarly, the house, built in 1996, is shaped in the same ovular design to allow for the greatest tolerance for external stress or energy. It features gently sloping walls angled at 4 to 5-degree angles, like the sides of the “waterbear,” to create a very low center of gravity that allows for stability in the event of an earthquake, while also minimizing resistance to wind or water. Tsui described the house in a natural disaster as “a low, stable boat riding out a shock wave.”

To be fair, the Fish House has never been tested out in a major earthquake. But Tsui says it’s performing admirably in energy conservation. The house maintains a temperature of 65 to 70-degrees year round with large domed windows that maximize heat and light absorption into the house, a natural air conditioner system utilizing the bay winds that are funneled into the front of the west-facing house, and natural insulation as most of the house is embedded in the ground.

Tsui said that the residents of his designs — including his parents — have all been pleased with the way that his buildings perform. And they like the aesthetics as well.

Wallet-friendly designs

One might assume that all of these ecological benefits come at a high price. However, Tsui’s environmentally-friendly designs are wallet-friendly as well. The 2,000 square-foot Fish House, for example, cost a total of $250,000 to build. “Architecture is for everyone,” Tsui argued. “We want to defy the socio-economic aristocracy of architecture.”

Healthy living is part of the design goals as well. Residents must physically generate power in many of the eight residential homes he has designed via stationary bicycles, and most of the homes are centered around vegetable gardens.

“We want people to physically participate in the designs,” Tsui explained.

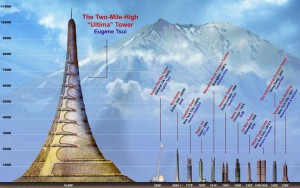

But Tsui’s “masterpieces” are certainly not for everyone. Typically, the neighbors protest vehemently (as they did with the Fish House) and have been known on several occasions to successfully block projects. Getting permits is a hassle, he said. Tsui dreams up buildings that few take seriously in this day and age. Say, a 2-mile tower shaped like a termite mound, which would be able to house San Francisco’s entire population. Apparently, San Franciscans haven’t taken to the idea of living like termites.

Nevertheless, Tsui has managed to see 16 projects in the Bay Area to fruition (three of which have been demolished) with seven more residential buildings in progress in the United States, as well as one home in Portugal.

Spreading the message

Tsui evangelizes his vision through his nonprofit Telos Foundation, which provides lectures and other educational programs. Over the past 23 years, Tsui’s firm has brought in more than 500 interns from all over the world as part of his mission to educate the next generation of architects.

Yeyo Nolasco, a senior undergraduate majoring in environmental analysis and art at Pitzer College, in Claremont, Calif., is one of Tsui’s newest interns. Nolasco is one of a handful of interns living with Tsui at Mount Shasta (where he has temporarily relocated his office while a new one is built in San Pablo). They are working on a zero-electricity building. Nolasco spent a night in the partially-completed building and reported back that “it’s a lot different” from a traditional house.

For one, there is no roof on the building (the roof will be made of petal-like sheets, which can be manually opened and closed), which allowed Nolasco to sleep with a full view of the night sky. Nolasco found the experience tranquil and deeply restful.

“How I wish everybody could experience this every night, because then, I am sure, people would realize that the way we live makes no sense at all,” she said.

With nothing but solar and water produced energy, the house serves as a reminder of what is really important in a world inundated with electricity-dependent technology. “We don’t necessarily need electricity as much as we think we do,” Nolasco said.

Among Tsui’s other projects in Northern California is his new office in San Pablo overlooking the San Francisco Bay, which will include an environmental education center that’s open to the public. The building will be located at 1675 Hillcrest Road and is expected to be completed sometime early next year.

Another concept piece Tsui is working on is an iconic building to frame the city of San Leandro with vertical gardens to grow food, a solar updraft tower to generate electricity, gymnasiums, government offices and more. The plans for this building have not yet been completed, or even proposed to the city, nor has a site been selected.

And Tsui is also working on the publication of his latest book on ecology with the University of Beijing, which is centered on looking to the natural world for answers to modern architectural and societal problems.

Jaquelyn Davis is a Bay Nature editorial intern.