Wilderness. It’s a word with a kind of electrical charge; merely to mouth it produces a vague thrill and an image of some place enchantingly alien to our daily lives: a perfect mountain meadow, a swamp that no path penetrates, a desert mesa under a trumpet-blast of stars. We’re a little short of such shiversome scenery in the Bay Area, yet wilderness is something we do have.

Meaning what, exactly? In a world thoroughly worked over by humankind, wilderness is our term for those places that seem the least altered, the least managed. It identifies the rawer end of a spectrum, with downtown San Francisco on one end and, say, the Wrangell Mountains on the other. But the word is elastic. It is often used in a place name, as in several East Bay regional parks with “wilderness” in their titles, or as a synonym for protected open space, as when Bay Nature titled a story about land acquisitions around Mount Diablo “Planned Wilderness.”

This loose usage complicates life for the people who are gearing up to celebrate a federal law signed 50 years ago on September 3, the Wilderness Act of 1964. For it was the purpose of that law to turn the wilderness concept from a squishy abstraction into something very specific, a land classification with legal meaning and “teeth.” A “wilderness area,” says the law, is “an area of federal land that appears primarily to have been influenced by the forces of nature” and that has been designated for preservation, within precisely surveyed boundaries, by an Act of Congress. Inside these limits, roads, mechanized access, and most forms of resource extraction are forbidden.

There were wilderness areas before the Wilderness Act, tracts set aside by the U.S. Forest Service, which could make or unmake them on administrative whim. With the passage of the act, the creation of wilderness areas became solely the prerogative of Congress—and fair game for citizen pressure and political horse trading. For wilderness advocates, this arrangement has worked out pretty well. Since 1964, in all political weathers, they have continued to get wilderness areas designated—on a much larger scale, in fact, than the authors of the act ever dreamed (though not as large as current advocates desire).

The National Wilderness Preservation System is now up to some 110 million acres; California has 15 million acres — about 15 percent of the state, second only to Alaska. Wilderness areas confer another layer of protection on lands inside national parks, national forests, national wildlife refuges, or areas controlled by the Bureau of Land Management. State parks in many states, including California, also contain wild areas classified under parallel state laws. Some Indian tribes have designated wilderness areas on reservation land as well.

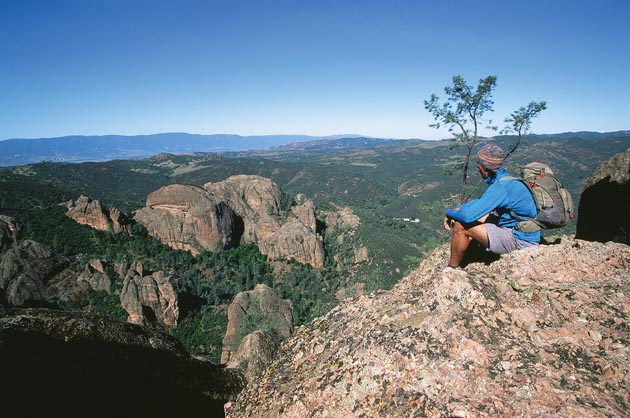

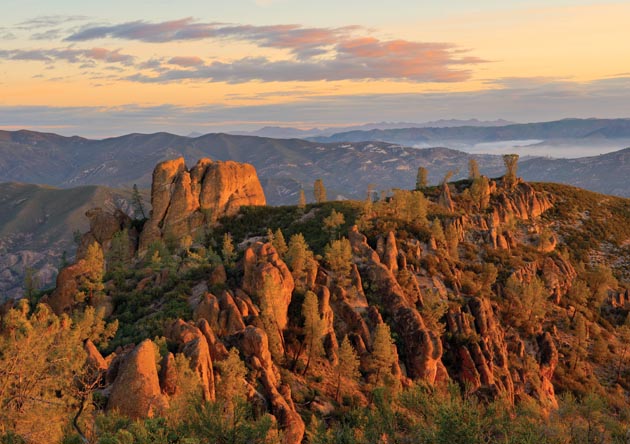

Even the San Francisco Bay Area, settled early and intensively, has a roster of officially designated wilderness areas. Parts of Point Reyes National Seashore are in the zone; so are all but one of the Farallon Islands. Henry Coe State Park has the large and remote Orestimba Wilderness, and Big Basin State Park contains the smaller, more frequented West Waddell Creek Wilderness. A bit south lies the backcountry of Pinnacles National Park; a bit north are the Cedar Roughs Wilderness near Lake Berryessa and the Cache Creek Wilderness, along the outlet stream of Clear Lake. Farther afield lie the great roadless areas of Mendocino National Forest, Los Padres National Forest, and the Sierra Nevada.

The local array shows that “wilderness” does not have to mean “remote” or “difficult to access,” and it illustrates several other aspects of wilderness areas in general: the reasons for their designation, the debates they engender, and the management issues they involve.

After the act passed, several federal land agencies were required to survey their holdings to determine which roadless areas might be wilderness candidates. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service looked at its Farallon Islands National Wildlife Refuge, 22 miles west of the Golden Gate, and found it good. Except for the largest island in the group, Southeast Farallon, these scattered seabird islets were indubitably wild, and nobody had plans to change that. It was an easy thing for the agency to recommend, and for Congress to create in 1974, a Farallon Wilderness consisting of all of 141 acres. (The act foresees most wilderness areas containing at least 5,000 acres but allows smaller ones if these are “manageable units.”) To put the wilderness rubric on the Farallones is what veteran wilderness advocate Phil Farrell of Palo Alto calls “labeling our jewels.”

Things got more contentious with the next two areas up for consideration: Pinnacles National Monument south of Hollister and Point Reyes National Seashore in West Marin, both managed by the National Park Service. In each case, wilderness designation became a way for advocates to head off some cherished development plans of the agency itself.

The chaparral hills and rust-colored cliffs and towers of the monument (since upgraded to a park) seemed obviously qualified for wilderness status, but there was disagreement about boundaries. Most significantly, the park service wanted to leave room for a new road connecting the two dead-end highways, one from the Salinas Valley and one from the San Benito Valley, that access the park today. On this and other points, wilderness advocates prevailed. There will never be such a road.

Emotions ran higher at Point Reyes. In 1971 the park service had just backed away from an astounding development plan for the new park: seven major recreational complexes, a clifftop parkway north from Bolinas, Limantour Estero reshaped into a pond for swimming and boating. Though the service promised a new vision, the old one was still fresh enough to suggest the value of an insurance policy in the form of maximum wilderness. At one hearing, a citizen challenged official reassurances: “Although you say you are dead set against [overdevelopment], who comes after you?” Advocates also sought to block one road that was still proposed: the Muddy Hollow connection between the Limantour area and Sir Francis Drake Boulevard.

The park service offered little resistance, and in 1976, Congress enacted most of the citizens’ plan. Nearly half of the park became wilderness, divided in four pieces. Most of the acreage of the Phillip Burton Wilderness (named after the powerful San Francisco Congressman who was a strong proponent of preservation) is in the southern portion of the national seashore, in two blocks separated by a road open to service vehicles. A third area includes Limantour Estero and Spit, with a section of hills up behind. A fourth is centered on the northern tip of the peninsula, Tomales Point, with a rather awkward tail draped the length of Point Reyes Beach (to preclude any thought of waterfront concessions or dune buggy access).

Point Reyes, a close-in area created by the purchase of private lands, is something of a limit case for the wilderness concept. It shows just how crowded, just how marked by human activity, and just how in need of management an area can be and still be wilderness by law.

You hear people scoff at applying the a “W” word to trails as busy as the route north from Palomarin to Bass Lake or the walk out to Tomales Point in wildflower season. In the early years under the Wilderness Act, government planners, and some conservationists too, felt that busy peripheral areas should be left out of wilderness or called by another name. The act, however, carefully describes wilderness as providing “an opportunity for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation.” Crossing that boundary does not have to mean being alone.

Point Reyes is also an extreme example of what has been called “creative” or “restorative” wilderness. The lands purchased for the park had been rather thoroughly occupied and altered, first by the Miwok Indians and then by early ranchers. This is especially true of the Limantour unit and of the Tomales Point area, once the prosperous Pierce Ranch. This kind of wilderness classification — offensive, if you like, rather than defensive — can involve eliminating historical traces. The first pioneer dairy on the point is an unmarked site in the Limantour wilderness.

Yet “creative” wilderness is implicit in the Wilderness Act. The Wilderness Society’s Howard Zahniser, architect of the law, vetoed the use of words like “pristine” or “undisturbed” to describe the lands at stake. To renaturalize formerly occupied lands is a legitimate choice. Whether it is the right choice in every case is another matter. Some think it was overdone at Point Reyes; some hope to see it applied there yet more widely.

Point Reyes also tests the hopeful idea that wilderness can be a zone free of human management: the faith that we can really simply draw a line, refrain from meddling, and watch an ecosystem prosper. Indeed, in the era of climate change, mass extinction, and the global free-for-all of shifting species, it may be malpractice not to meddle. Parts of the Point Reyes wilderness, for instance, are afflicted by invasive Scotch broom and giant South American grasses. The Wilderness Act has been interpreted to allow intervention in such cases if the “minimum tool, equipment, or structure” is used. Near Wildcat Beach, ropes and herbicides were backpacked in to deal with jubata grass proliferating on cliffs. At Abbotts Lagoon, an effort to remove European dune grass for the benefit of native plants and birds required more horsepower: In this case, the “minimum tool” was judged to be a bulldozer.

And how does the Drakes Bay Oyster Company fracas fit in? In the 1970s, environmentalists sought wilderness status for Drakes Estero (linked to the neighboring Limantour unit), but would have let the oyster farm continue as a “nonconforming use.” The park service objected that this sort of exception was stretching the Wilderness Act too far, and Congress instead placed these waters in a novel holding category, “potential wilderness.” Today the service and major environmental allies want the oysters gone and the wilderness classification fulfilled, while other greens and agricultural supporters push back with talk of sustainable food production. Sometimes painted as a deep ideological battle, this one seems to me more like a border dispute arisen, almost by accident, between essentially compatible players.

In 1974, the Legislature passed the California Wilderness Act for state-owned lands, giving the California State Park and Recreation Commission the designation authority. In 1982, the commission established the West Waddell Creek Wilderness within Big Basin Redwoods State Park. Amounting to almost a third of the park, the tract contains mature second-growth forest and popular Berry Creek Falls. This classification may seem to be a case of “labeling the jewels,” but it has consequences. Deadfalls are cleared with handsaws, not chain saws; permanent bridges have given way to flimsier “wash-away” ones; and the portion of the Skyline-to-the-Sea Trail within the wilderness is destined to remain forever single-track and closed to mountain bicycles.

Across the Santa Clara Valley, in the heights of the Diablo Range southeast of San Jose, lie Henry W. Coe State Park and the wilderness called the Orestimba. If your sense of the wild does depend on solitude, the Orestimba, whose boundary lies 12 miles from the closest public road, is a good place to find it. This rolling blue oak savanna is the first area on our list that is large enough to accommodate that typical wilderness activity: dispersed backpack camping.

Yet the Orestimba is in a sense the one that got away. The state’s first wilderness plan, in 1978, would have included almost the whole of what was then a 13,000-acre park. When a vast land acquisition expanded Coe Park sixfold, advocates inside and outside of government sought to expand the wilderness proposal to match. Instead, the state parks commission limited its final wilderness designation in 1985 to a far reach of the newly acquired land, some 22,000 acres in two units separated by a fire road. Additional acreage was to be studied, but the study apparently never came to pass. “The state parks department missed a chance to think big,” Phil Farrell says. “They could have created a really magnificent Coast Range wilderness.”

The latest additions to our wilderness list lie on the region’s northeastern rim and are administered by the Bureau of Land Management. This federal agency, which manages vast tracts of mostly arid land, came late and reluctantly to the wilderness study game. In 2006 Congress overrode the BLM’s wishes and designated two areas. The Cedar Roughs Wilderness Area, on the skyline west of Lake Berryessa, is a remote serpentine barrens that supports the rare Sargent cypress and Napa County’s only known resident population of black bears. A little north, the Cache Creek Wilderness surrounds the rugged middle reach of the little river, patrolled by bald eagles and popular with rafters, that drains Clear Lake. In both cases, wilderness status meant closing a number of minor roads; at Cache Creek, some potential mining and energy development, not very promising, was foreclosed. Wilderness here does not head off some blockbuster invasion but simply halts what Vicky Hoover of the Sierra Club’s California Wilderness Committee calls “the normal trend of development” that can, over time, transform the face of the land.

The golden anniversary of the Wilderness Act is a time of thought as well as celebration. A movement whose leaders are mostly white and largely of pre-digital vintage knows it must find more recruits among the young, the brown, and the wired. Meanwhile, the wilderness concept itself, and the attitudes of its supporters, have faced attack from unexpected quarters.

Wilderness, some critics complain, is a sentimental idea, a romantic indulgence. There is no such thing as a “primeval” place. The Native Americans were there first, followed in many cases by farmers and loggers; and the broader human influence is inescapable. To idealize wilderness is to devalue all that land — the great majority — that can never be considered for this specialized zone. Eminent historian William Cronon decries “wilderness dualism,” which, he says, “tends to cast any use as abuse, and thereby denies us a middle ground in which responsible use and nonuse might attain some kind of balanced, sustainable relationship.”

From what seems the opposite direction comes another argument: that the wilderness movement is too timid. Drawing lines around a few scattered areas, largely high, cold, or dry, or otherwise infertile, is a “strategy of weakness,” some say, doing little to help the biosphere adapt to climate change and other human-caused disruptions; what is needed is a vast continental system of protected corridors along which species can migrate and shift. In the 1990s, a group of scientists and activists, joined under the banner of the Wildlands Project, called for a network of wilderness areas and gently used buffer zones covering about half the area of the United States.

The two lines of criticism converge on a single point: that wilderness as we know it is a limited tool. This seems fair enough. It does not follow that it is a bad tool. There is much to be gained by setting aside certain less-developed lands explicitly as roadless and outside the usual range of human activity. This is, as academic critics point out, a highly artificial, culturally determined act. The Sierra Club’s Hoover puts it a little differently: “Wilderness is an achievement of American culture,” she says.

As if in response to the critics, two local efforts aim to integrate wilderness into a broader and subtler program of land protection and management. At Pinnacles, the park is working with the Amah Mutsun people, descendants of a group who once ranged the park and harvested resources within it, to relearn the precolonial management practices that helped shape the landscape Europeans first encountered. In 2012, a controlled burn took place, partly inside the wilderness boundary, with the objective of encouraging the growth of two native plant species used in basketry. “This is the first time in well over 100 years we’ve been able to deliberately start a cultural burn anywhere on our territory,” says Chuck Striplen, a tribal member who is also a scientist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute. The burn site yielded an abundant wildflower show, though two subsequent dry years have made it hard to judge how the two target species—deer grass and root sedge—will respond. The experiment and the relationship continue.

Up north, a group of citizens who began by lobbying for the Cache Creek Wilderness are now seeking to assemble a vast sweep of protected lands to be known as the Berryessa–Snow Mountain National Conservation Area. The spine of the plan is the innermost ripple of the Coast Range, known in Solano County as Vaca Mountain and farther north as Blue Ridge. The concept is to wrap core wilderness areas in a matrix of less strictly managed recreation lands, with working agricultural landscapes alongside as well.

Indeed, it might be said that the entire Bay Area, with its ever-expanding greenbelts like the one centered on Mount Diablo, is evolving in the direction so boldly (and controversially) sketched by the Wildlands Project. When wilderness areas are seen in this context, much of the tension surrounding the concept disappears. Stewardship? Of course. Wilderness? Absolutely.

I recall how moved I was, many years ago, when I first stepped across the boundary of a wilderness area (it was the Hoover Wilderness near Yosemite). Behind the modest boundary notice, the scenery was not different; the flowers no more vivid, the waters no more clear. What changed was in my mind. I knew that I was entering a zone where society had decided to arrest, even reverse, the sometimes slow but seemingly relentless process by which land becomes more civilized, more imprinted by human needs, more doodled on by random human markers. Almost anywhere else, even in parkland, I may wonder, What are “they” planning to do here next? Within these boundaries the answer is known: nothing, or as little as “they” can.

I’ve learned a lot since then about the complexities involved in carrying out such a decision, but the feeling has not died. It is a kind of relaxation, a dropping of mental guard. Looking out from the roadless clifftops of Point Reyes toward the black-on-silver outlines of the Farallones; enclosed by the fir woods of Inverness Ridge or the redwoods of West Waddell; tramping a brushy ridge near Cache Creek or descending among irises and oaks toward Orestimba creek, I can forget the marginal puzzles and disputes and simply be glad for places like this—and for the laws and stubborn human efforts that provide their enduring shield.