Clear Lake, the subject of our forthcoming April issue cover story, is a place of plenty: It’s the largest and oldest lake in California. Grebes nest here by the tens of thousands. Birders and anglers flock here for good reason — it’s got some of the best birding and fishing in the state.

But several species of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) have a field day of their own here, and they produce foul-smelling toxins that can make those other superlatives a bit less compelling.

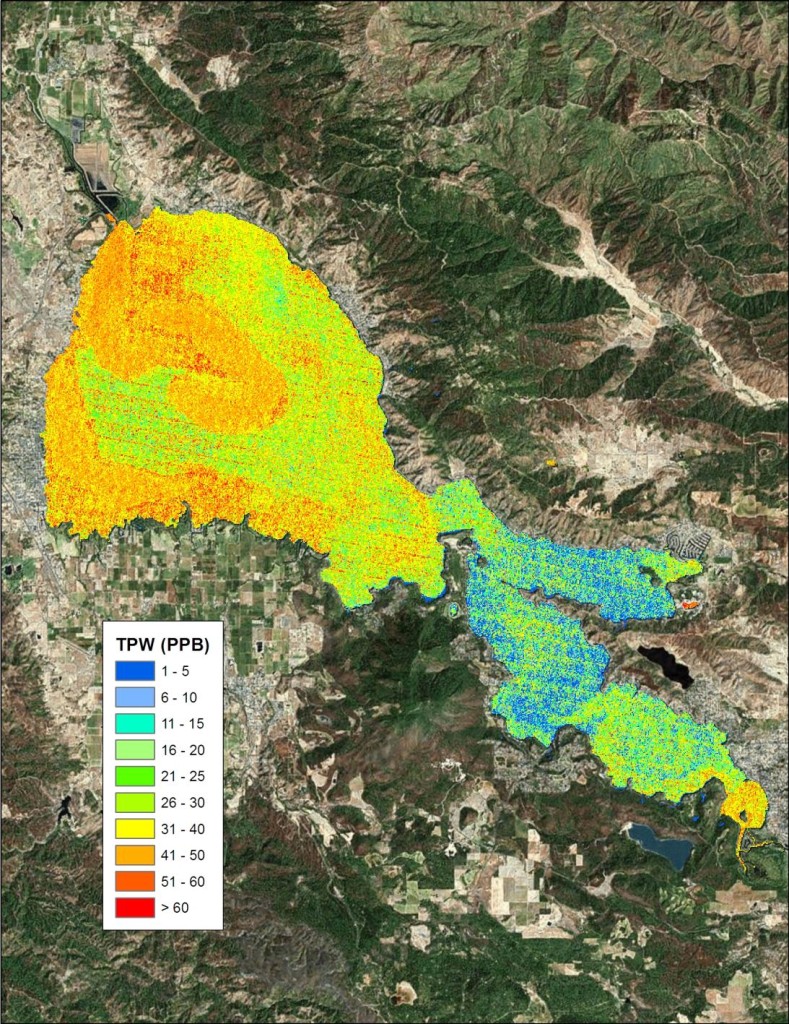

This year, Lake County officials are embarking on a new high-tech method of solving their algae problems: Combining U.S. government satellite imagery with proprietary algorithms developed by an Ohio-based company, Blue Water Satellite, to pinpoint areas high in phosphorus, which is a key driver of increasingly common Clear Lake algae blooms.

“This is the oldest natural lake in California, maybe the oldest lake in the Western Hemisphere. It’s ancient,” says Charles Lamb, who cofounded Konocti Regional Trails. “We want to protect this for future generations, so that in 20 or 25 years, you don’t have these kinds of cyanobacteria blooms anymore.”

Lamb was one of the chief proponents of using Blue Water’s satellite imagery analysis to try to isolate specific sources of phosphorus pollution in the lake. Potential culprits range from illegal marijuana farms to erosion-inducing off-road vehicle use to large-scale agriculture to runoff from roads and parking lots.

Thanks to satellites and algorithms, the county can zero in on hotspots spread over 40,000 acres of surface water and 300,000 acres of surrounding watershed, an area that could never be sampled using traditional methods.

“You can really target remediation rather than trying to remediate all over the place,” says Reid McEwan of Blue Water Satellite. “Clear Lake is huge, but when you look at the imagery, there are only a few spots that are the biggest sources.”

So far, the county has gotten just the first three of the 24 scans it has ordered for the next two years. “The overall goal of this project is to bring the phosphorus levels down to pre-modern-man amounts,” says Lamb, “We’re excited from the results we’re seeing so far, but it’s going to take some time.”

Lamb explains that even if all phosphorus inflow stopped tomorrow, it might be as long as 15 years before there would be major changes in the lake, where enough phosphorus is stored in sediments to fuel algae growth for many years to come.

And rising temperatures due to climate change won’t help matters: A report prepared for the Central Valley Water Quality Control Board in 2011 states that warmer temperatures give cyanobacteria “a direct competitive advantage” compared to other microorganisms.

“You’ve got to start sometime, says Lamb. “Unless this county does something about it, it is never going to get better.”

One further bit of complexity in this story is the question of just how much better it ever was. On the one hand, the 2011 water quality report by researchers from UC Santa Cruz and Davis lays out a rather depressing record of degradation here over the past century: “Clear Lake has been severely impacted by human activities. Since 1914, water levels have been regulated by Cache Creek dam and development in the watershed, especially since 1930, has led to the eutrophication [nutrient overload] of the lake.” The researchers go on to recount further indignities at the hands of mines and quarries that have left the lake with mercury levels that are “some of the highest of any lentic [lake] system reported to date.”

Sounds grim. Yet the county’s own overview of algae in the lake says, “Clear Lake has been a shallow, productive system, essentially similar to the modern lake since the end of the Pleistocene Period.” That’s about 10,000 years ago. And the UC researchers found records of algae blooms as far back as 1873, well before the surrounding watersheds were seriously altered.

So is the algae a new ecological problem or an annoyance?

Biologist Jim Steele, a retired division chief for the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, helped clear that up for us, with a version of, well, it’s complicated. As is so often the case with natural systems.

Here’s Steele: “”It’s got to be one of the most complex systems in the world, and I have studied lakes all over trying to look for a lake with similar conditions. Clear Lake has treasures you wouldn’t believe — a lot of different ecosystems overlap each other in ways that don’t happen anywhere else in California or maybe in North America.”

But humans have made serious impacts since the arrival of Europeans, he says, not least is that about 8,000 of the 9,000 acres of filtering wetlands surrounding the lake were destroyed. “You also have a lot of land disturbance from ATVs, and you have maybe a hundred square miles of impervious surface with roads and parking lots. And then on top of all that, one end of the lake has shallowed up because of the sediment coming in, so the sunlight can penetrate the whole lake.” And all that sunlight helps unlock even more phosphorus in the sediment, which fuels more algae blooms.

He sums it up: “If humans weren’t here, this would just be the most gorgeous spot.”

But that, of course, is not the stated goal of the satellite imaging project.

“I’m hopeful that six months to a year from now, we’re making changes,” says Scott de Leon, Lake County’s director of water resources. “Or at least we’ll have some ideas for changes that we could be making to help reduce the amount of nutrients.”