ane Hart stakes her vigil almost daily at Lookout Point near the Cliff House. She sets and tunes her Swarovski spotting scope to maximum viewing capability, and scans the shoreline and out onto Seal Rocks for one of California’s most familiar seabirds. A former teacher turned fervent birder and Golden Gate Audubon volunteer, Hart has been watching a breeding pair of black oystercatchers on the rocks for the last 4 months. Despite a number of studies conducted in the northern part of their range, from the Aleutian Islands to Oregon, there hasn’t been much research done on black oystercatchers in California and Baja. So the Audubon Society set out to learn more, and when the group asked Hart to participate in a study of the species’ nesting and breeding habits, she jumped at the chance. Now, most mornings you’ll find her on the high rocks above the crashing waves, watching the birds fish and nest, listening for the piercing whee-wee-wee-wee the birds use to defend their territory and attract mates, taking notes on their movements and activities.

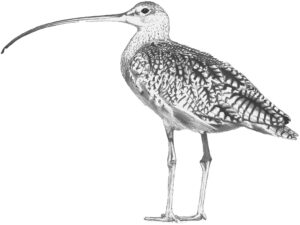

With a stark black nape leading down to a dark brown body, a bright orange bill, and that piercing alarm call, the black oystercatcher is a popular sight in the Bay Area. They can be spotted scanning their rocky intertidal ecosystems from above, diving into the surf to pry their favorite prey-mussels, chitons, and limpets-from the adhesive havens of the rocks below. Although migratory in other parts of its range, the black oystercatcher is unique for being the only seabird in the Bay Area that does not migrate. They instead stay year-round in bowl-shaped cavity nests on rocky coastal cliffs and intertidal zones.

Climate change isn’t kind to range-limited animals that live near oceans. Audubon’s 2014 climate report predicts the black oystercatcher’s winter and summer range could shrink considerably – and quickly, with changes evident perhaps by as soon as 2020. By mid-century, the range might shift northward up the Pacific Coast, into Oregon and Washington, which could mean an even higher risk of extinction for the Bay Area population.

ut the birds seem comfortable enough for now: for the last four years 80-100 Northern California oystercatcher nests have been tracked annually, with Mendocino, Madrone, Morro Bay, Monterey, and Redwood Regional chapters of Audubon California harboring successful breeding populations. The first Audubon population assessment of black oystercatchers in California, published in 2011, showed nesting sites ranging from coastal San Luis Obispo north to coastal Humboldt County.

Audubon’s climate report listing of the black oystercatcher is mainly for three reasons: there aren’t that many of them left on the Pacific Coast, they don’t have high breeding success, and most of all, they’re shorebirds, completely dependent throughout their lives on the rocky intertidal habitat for food and shelter — and the shoreline is moving with sea level rise. Researchers at Point Blue conducted a vulnerability analysis of birds in the Bay Area in 2008, with the black oystercatcher coming out near the top of the list as the most vulnerable.

But big-picture models can’t necessarily capture the nuance of an individual species, and in the case of the oystercatcher, there’s quite a bit of nuance. Audubon California Marine Program Director Anna Weinstein, who with more than 150 shorebird biologists in 2011 conducted the first survey of the black oystercatcher’s distribution and abundance in California, said that there’s still basic information to find. “There’s a lot of work to be done, more than you would think for such a charismatic bird,” she says. “We’ve only collected baseline information — distribution, abundance, breeding success.”

In an article in Marine Ornithology in 2014, Weinstein and her colleagues suggested, in fact, that Northern California had more black oystercatchers than previously thought, and also might be a valuable climate refuge for the birds. Black oystercatchers’ northern nesting sites tend to be closer to the water, and so face a high risk of inundation, while California and Southern Oregon have a marine terrace that provides nesting sites higher above sea level – offering protection, somewhat, against sea level rise.

The 2011 survey also estimated the number of black oystercatchers in the state at around 4,000-6,000, considerably higher than previous estimates. Audubon’s annual Christmas Bird Count has shown a stable global population, and an increase in black oystercatchers in both the Bay Area and California.

“Yet,” the paper concludes, “even if this is the case, the species is highly vulnerable to decline given the gravity of the threats faced by this species and all shorebirds.”

Changes in intertidal habitat, as well as warming and acidifying oceans, could affect the food the birds rely on. Human disturbance is also a threat, which is why Audubon is trying to run an outreach campaign to keep visitors away from the birds. “People have been very responsive,” Weinstein says. “They’ll say, ‘Oh, I didn’t know that I was driving the bird away from its nest by trying to get closer to it.’ They actually listen, and then begin to realize their impact, which is crucial.”

People want to save what they are familiar with and what they love, and the black oystercatcher is a familiar and beloved flagship species in the Bay Area.

“They have a chance,” Weinstein says. “These birds are tough, they’re survivors that chase away predators such as ravens and red-tailed hawks, and I have a sense that they will prevail and adapt to climate change. They are a bird for today’s world.”