Words by Bay Nature staff; illustrations by Jane Kim.

California tiger salamander. (Illustration by Jane Kim)

Sexy salamander season

As the rains kick in, yellow-and-black California tiger salamanders (Ambystoma californiense) begin their rubbery-legged, perilous march to vernal pools and other water bodies to breed, mainly in the Bay Area and Central Valley. These salamanders likely find their destinations by sniffing them out, possibly by eyeing the stars and moon. Of three distinct populations, two are federally endangered and one is threatened.

After a few years, the salamanders are of an age to mate. A male and female find each other at the vernal pool, and the male leaves a capsule of sperm, which the female then pulls into her body. She’ll lay the fertilized eggs—on average 814 of them—a few at a time, on the stalks of aquatic plants. They grow there like translucent pearls, each bearing a tiny salamander larva. Gills, a tail, and tiger spots can be seen wiggling just before larvae hatch at two to four weeks. By then, the adults have long since gone.

Fireball. (Illustration by Jane Kim)

Great balls of fire

During the long, dark nights of winter, look up! Colorful fireballs will be hurtling across the sky the last week of December until mid-January. Fireballs are particularly bright meteors created when unusually large meteoroids burn up on entering Earth’s atmosphere. Their red, blue, or green colors correspond to the elements in the meteoroid and its velocity. Fireballs are a signature of the annual Quadrantid meteor showers, and astronomers forecast 111 meteors an hour for the time around the shower’s peak in the Bay Area on January 3. The meteors are born from the debris of a two-mile-wide asteroid discovered in 2003.

Witch’s butter. (Illustration by Jane Kim)

We can’t believe it’s not butter

During a wet ramble, a curious and bright yellow fungus might catch your eye and cause you to declare, “If witches eat butter, this is definitely what it looks like.” We’re pretty sure that’s the reason for “witch’s butter,” the best of Naematelia aurantia’s common names. The gelatinous yellow folds are its fruiting bodies, and while edible, they are not spreadable, and, sadly, taste neither like butter nor anything else. Include them in salads for color? The species parasitizes another fungus, the false turkey tail (Stereum hirsutum), which lives on oaks and other hardwoods.

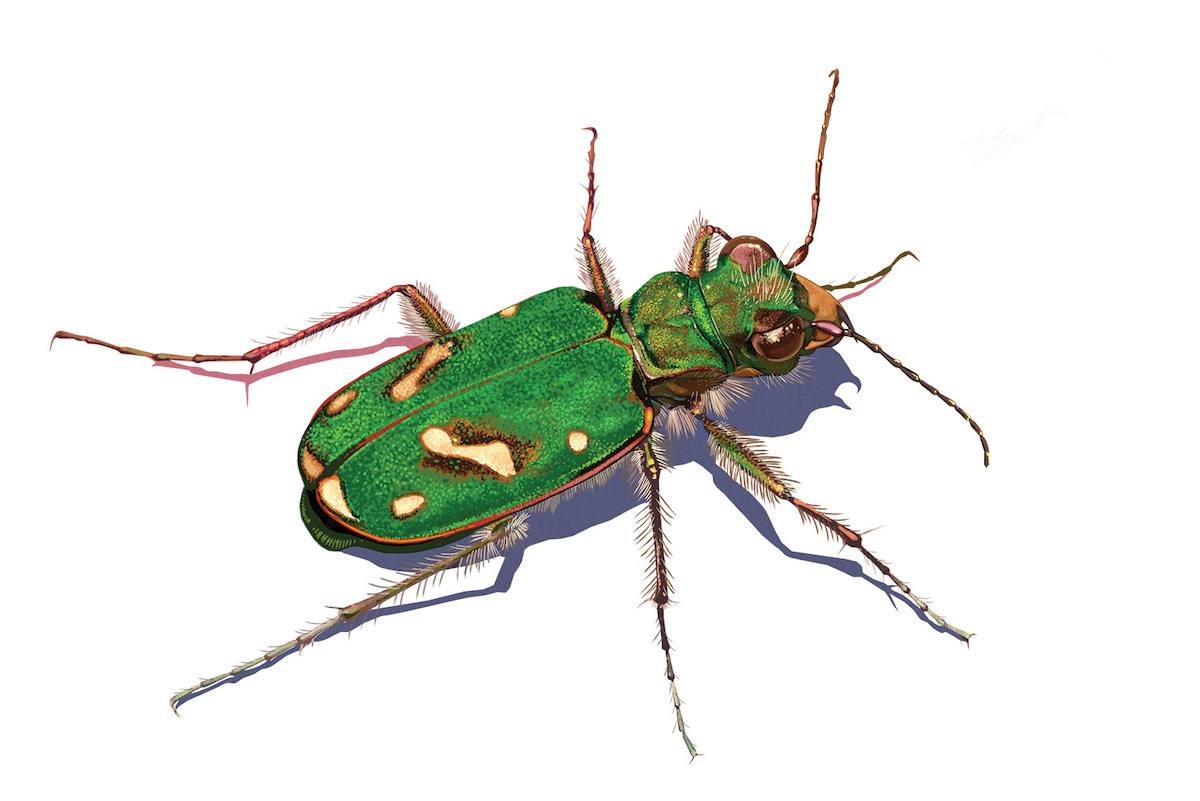

Ohlone tiger beetle. (Illustration by Jane Kim)

Splendor in the grass

Amid tufts of purple needlegrass and California oatgrass in Santa Cruz County scurry the fabulous iridescent-green, and federally endangered, Ohlone tiger

beetles (Cicindela ohlone). The adults emerge from their burrows during the winter, unusual among tiger beetles. Living up to their predatory name, they chase down arthropods for a meal, while larvae ambush them from the shadows.

Allen’s hummingbird. (Illustration by Jane Kim)

Sassy hummers

There’s nothing like an iridescent bronze-bedecked neck to brighten the winter gloom. When Allen’s hummingbirds (Selasphorus sasin) arrive from Central Mexico in the coastal Bay Area, as early as January, the bronze, white, and green males begin a flashy courtship flight. Puffing out his gorget feathers, the male zips side to side in front of the female, or he climbs 100 feet in the air and divebombs, only to pull up short before her: “I’m here!”

Pacific hound’s-tongue. (Illustration by Jane Kim)

Pacific hound’s-tongue

Blue is a rare-ish color in nature, when you put aside the sky and ocean. By one measure, less than 10 percent of flowers are blue. How lucky are we that the often sapphire-hued Pacific hound’s-tongue (Adelinia grandis, formerly Cynoglossum grande) blooms in the Bay Area during winter. The plant grows in the shade of oak woodlands and chaparral and is the preferred host for the caterpillar of a pretty black and pale-spotted moth (Gnophaela latipennis). The hound’s-tongue’s large leaves, which the caterpillar likes to eat, earned the plant its common name.