(Photo by Carlos Porrata)

Dave Press slides on a pair of aviator glasses and begins hiking up a hill, only to cast them aside at the top for binoculars, shielded by a National Park Service baseball cap. He scans an adjacent hillside for the tule elk that are browsing beyond a stand of eucalyptus trees, the tallest foliage on a landscape dominated by low-lying coastal scrub. Off to his right gleams Tomales Bay, and before him lies Tomales Point, the northernmost tip of the Point Reyes National Seashore.

“We’ve got a group up there in a kind of tricky spot,” says Press, the wildlife ecologist for the park, who grew up in western Marin County and knows the territory like the back of his hand. “We can’t see them all from here.”

“Some are bugling down there,” says Caitlyn Bishop, a PRNS summer intern.

“Yeah, I thought I heard that,” Press replies. He pauses and plots his next move, realizing though that the elk are going to smell us coming. “Unfortunately, the direction I want to approach them from is also the direction of the wind; such is life.”

On this day in late July, I’m accompanying Press and his team of four as they fan out across the windswept hills to find and count every elk within the 2,600-acre Tule Elk Reserve, where the elk are separated from the rest of the park—and its historic cattle ranches—by an eight-foot-high fence. Press and his crew typically tally the population once a year in December, but since 2012, the elk population has plummeted by nearly half—from 540 animals to 286 in December 2014—so the park service has been hit with questions and concerns from the public about the steep decline.

Listen: Wildlife Ecologist Dave Press Discusses Tomales Point Elk

Some wildlife advocates have termed the situation a “die-off” and accuse the park service of allowing the elk to perish behind the fence that prevents them from finding enough food and water. Park service officials have a different view of what caused the population drop, and are hoping that new data will help address these concerns, especially as visitor interest peaks during the fall rutting season. “We have a docent program on weekends during the rut,” says Press, “so we’d really like to share updated population data with the public because this has gotten a lot of media attention and we get a lot of questions.”

Counting elk, by the way, isn’t easy. Elk don’t let you get too close and the herd has a habit of partially disappearing over the undulating hillsides like a mirage. Sometimes the native ungulates are so still and blend so well into the landscape with their tan-colored hides it’s hard to know whether you’re looking at an elk or a boulder. “Oh these guys. I’m not happy with where they’re hanging out right now. This is why I want a drone,” Press deadpans.

We trudge around to the far side of the hill, following his game plan to nudge the herd into a valley for better visibility, but the elk are getting nervous. Two cows raise their heads and look directly at us for a minute, then suddenly run back up the hill. Press strikes off to flush the herd back downhill where he wants them. He disappears into the distance, a lone figure trying to make the wild do his bidding.

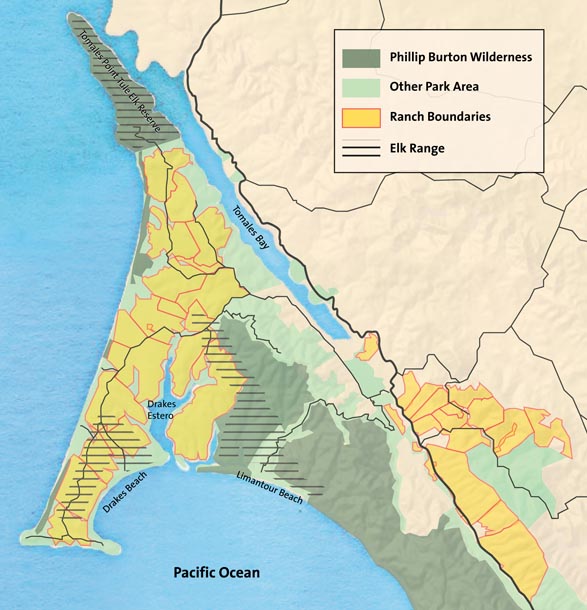

Managing the wild at the Point Reyes National Seashore is more complicated than simply protecting the park‘s many natural assets. This is the only national park to combine wilderness areas with ranching, and the debate over the elk is the latest example of the difficulties that can arise from incorporating a legacy of working landscapes into a national park. Recently, a decade-long political and legal battle over an oyster farm’s use of Drakes Estero in the central section of the park ended with the park service removing Drakes Bay Oyster Company from the area designated to become a marine wilderness. Ranchers at the seashore have an arguably more secure position than the oyster company, though one that also raises issues when it comes to managing wildlife. Currently, the most salient issue is the conflict between the ranchers and a more recently established free-roaming elk herd that is grazing on pastures in the central portion of the park.

Since its creation more than 50 years ago, PRNS has straddled its dual—and sometimes incompatible—mission of protecting wildlife while ensuring the survival of historic ranches in recognition of their cultural significance. The arrangement stems from the park‘s enabling legislation that allowed the park service to acquire the dairies and ranches within the park boundaries while issuing permits to nearly a dozen longstanding ranch families to continue operating in designated pastoral zones that comprise about a third of the park’s total acreage. This arrangement saved a national treasure from development but created the potential for ongoing tension between those trying to make a living on the land and those who view the park as a place primarily for wildlife protection and public recreation.

In an effort to better thread the needle between these sometimes conflicting aspects of its mission, the park service will release a long-awaited ranch management plan in 2016 intended to guide both future ranch operations and management of the free-roaming elk in the pastoral zone.

Tule elk, the smallest of the four surviving elk subspecies in North America (compared to Roosevelt elk, Rocky Mountain elk, and Manitoba elk), are endemic to California. A dominant grazer wherever they set foot, tule elk once numbered 500,000 across the coastal regions and inland basins of California, with a thousand alone on the Point Reyes Peninsula. They are majestic animals, particularly in the rutting season, when the normally reclusive bachelors, sporting impressive racks, make high-pitched whistling sounds, called “bugling,” as they duke it out for harems of females. Following the mating season the males drop their antlers, then break away into small, tight groups as they go into velvet.

Listen: Tule Elk Bugling

Hunting and agriculture had eliminated all but a handful of tule elk by 1874 when, as the story goes, cattle baron Henry Miller discovered a pair on his huge Kern County ranch and set up the state’s first tule elk reserve. For the next century, the species faced extinction until the U.S. Congress passed a law in 1976 directing federal agencies to make lands available for reintroduction of tule elk into their historic range. Point Reyes was identified as a potential site and in 1978 ten elk from the San Joaquin Valley were relocated to Tomales Point, which was fenced off to separate the elk from the ranch operations in the park.

However, by 1990 the “new” herd at the Tomales Point Tule Elk Reserve had grown large enough to spark concerns about its potential impact on other protected species and habitats. With no natural predators on the point, except for the occasional mountain lion, all that appeared to keep elk numbers in check was the availability of forage. Following the release of a 1998 elk management plan, the park service ultimately moved 28 animals from the reserve to a wilderness area further south in the park, inland from Limantour Beach, founding the first free-roaming herd at the seashore. Much to everyone’s surprise, soon after the relocation, two radio-collared females turned up on the pastures above Drakes Beach, on the other side of Drakes Estero. They returned briefly to the Limantour herd for the rut but then went back to the new Drakes Beach territory to calve. In 2001, a young male joined the pioneers and a small third herd was established.

Timeline: Tule Elk at Point Reyes

Great for the elk, but not for the ranchers, because these elk were no longer in a wilderness area but in the designated pastoral zone leased by the ranchers to graze their livestock. At last count in 2014, the herd there had grown to 92, to the consternation of the ranchers: An adult male can eat up to 15 pounds of forage a day. “If it hadn’t been for those two females that unpredictably bolted from the release site, we might not have ended up in this situation,” says Press, but then concedes, “it could have been just a matter of time.”

The rebound of tule elk from near-extinction is one of the state’s great species recovery stories—some 4,300 inhabit public reserves and private land throughout California—but those at Point Reyes present a particular conundrum. “It’s very different at Point Reyes because you don’t have the population management tools you would use on any other elk herd,” says Joe Hobbs, the elk and antelope coordinator for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Elsewhere, when elk populations get too large or troublesome, hunting tags are issued (California has 24 elk hunting zones), or the elk are relocated to faraway spots. But hunting (particularly in a national park) is not going to fly in Marin County. And relocating animals to another area of the state has been nixed because the Point Reyes elk have a history of harboring Johne’s disease and CDFW doesn’t want to risk spreading this potentially fatal pathogen to disease-free herds.

That’s left the park service to try arguably less effective techniques: contraception (too labor intensive); hazing the animals away from pastures (they return); and relocation to wilderness areas in the park (again, they return). Elk are lovely yet stubborn creatures.

“They’re just being elk,” says Hobbs. He explains that once they establish a home range it can be extremely difficult to break them of their patterns, so no rancher wants elk to home in on his or her pasture. “I think they get into trouble because of their size. They can break a fence, and they do eat a lot.”

Some believe the debate has been framed entirely wrong. According to Jeff Miller, a Bay Area spokesperson for the Center for Biological Diversity, the park’s priority should be to conserve wildlife, not provide space for agriculture.

In April, the Arizona-based nonprofit sent out a press release alerting the public to PRNS survey data that showed a 47 percent decline in the Tomales Point herd from 2012 to 2014. CBD posited that the elk had died “likely due to lack of access to year-round water” after some of their watering holes dried up and they couldn’t roam to ponds outside the fenced reserve. Conversely, CBD pointed out, the free-roaming herds were booming.

“The only real management difference there is the fence [at Tomales Point],” says Miller. “In a drought, elk are going to move around to find the water and forage they need—if they’re allowed to move.” CBD wants the park service to let the elk herds roam where they will. “It’s time to start having a conversation about taking down that fence,” says Miller.

Others picked up the cause. WildCare, a San Rafael-based animal rescue center, contends that the Tomales Point elk are essentially living in park service confinement and with that comes the responsibility for the service to keep them alive by ensuring they have enough water. “It’s not okay to provide insufficient care for confined animals,” says Kelle Kacmarcik, WildCare’s advocacy director. “If animals were to die in a zoo setting because of lack of food or water it would be criminal.”

But taking down the fence would disturb the uneasy peace with the nearby ranchers and supplementing water to the Tomales Point herd could unleash a new set of problems. The park service’s practice is to let nature take its course, and notwithstanding the presence of the fence, that means not creating artificial conditions that could influence the herd’s size or behavior. “It’s a delicate balance,” says Melanie Gunn, a PRNS spokesperson. “We want the elk to self-regulate, but if it gets as dry this year as it has the last couple of years, we will bring in water.”

Listen: PRNS Spokesperson Melanie Gunn Discusses the Park’s Plan

In the meantime, park service officials are trying to understand, and communicate to the public, how the Tomales Point herd could have declined by nearly half in just two years. And based on their research and observations, they don’t believe that dehydration, or even adult mortality, is the full story. “People have this impression that animals were pushing at the fence and piles of bones were lying about. But neither of those things were happening,” says Gunn who sports a Smokey the Bear hat. “It’s a fenced-in herd, but it’s not like they’re in a corral.”

There were no signs of elk trying to escape the reserve, Gunn says, and in fact one group has remained up at the northern tip of the reserve, far from the fence, with seemingly little interest in leaving.

On a morning in late June, Press, Gunn, and I stood out on the elk reserve watching a group of females, one nursing a calf. Calf numbers had dropped from 101 in 2012 to 23 in 2014, an indication that the females weren’t giving birth. Press has a theory that the animals could be suffering from a mineral deficiency, a possible drought-related lack of copper in the forage that could make them more susceptible to disease and parasites, or cause reproductive disorders. Recently, a necropsy on an elk that had died in a road strike revealed a copper deficiency, a phenomenon that had also been noted in the Point Reyes herd following its introduction in 1978.

But while the drop in the birth rate would lead to a lower population over time, it doesn’t account for the steep decline in the number of adult elk in such a short period. “I think the best way to say it is, it’s drought related,” says Press. “People are saying they died of dehydration or starvation, but the exact cause of death we don’t know.”

Park service officials maintain that, whatever the cause, the herd‘s eventual decline was to be expected, although not necessarily its rapidity. With 540 animals on Tomales Point in 2012—that’s more than 100 elk per square mile—the herd could well have exceeded the reserve’s carrying capacity. Three decades of elk survey data show that every time the herd has risen above 500 animals—in 1998, 2008, and 2012—it has dropped back down (although the 1998 decline coincided with contraceptive trials and the relocation of animals to Limantour).

“A die-off might be perfectly natural and wild. That’s often what happens when you don’t have enough resources,” says Laura Watt, a Sonoma State University professor in cultural resource management who has written a forthcoming book about the “paradox of preservation” at PRNS. But it can be a difficult scenario for the public to swallow, she says. “People seem to want elk to be both wild and managed simultaneously.”

One thing’s for sure: A carrying capacity hasn’t been reached for the free-roaming herds. Ten miles to the south of Tomales Point, the Drakes Beach herd is booming on pastureland, even in the midst of the drought.

The grazed pastures of the coastal hills that rise up behind Drakes Beach are where elk and cattle mix it up the most. On any given day, they bed down feet from each other, seemingly at peace beside their fellow ruminants. But less so with the ranchers, who complain that the elk break through cattle fences, eat too much from the pastures, and jeopardize the ranches’ organic status, which requires that one-third of a cow‘s diet be foraged material (limiting how much supplemental feed the ranchers can provide).

“There is a large herd of [elk] cows, calves with two large bulls, and other groups of bachelor bulls that are present daily,” writes Nichola Spaletta of C Ranch, perhaps the most impacted ranch, in an email. “Our ranch does not have the resources to support these increasing numbers of elk that feed and water themselves in our rented cattle pastures, especially during this horrible drought.”

Spaletta declined to be interviewed directly for this article, as did other ranchers, citing bad experiences with the media. Besides, they are waiting for the park service to release the long-awaited Ranch Comprehensive Management Plan in 2016, which will spell out a strategy for managing the free-roaming elk as well as provide for continued ranching. Among the topics: allowing ranchers to “diversify” to chickens and row crops, even B&Bs. Ranchers will almost certainly be granted new 20-year leases, a concession made to assuage fears that the fiercely contested closing of the Drakes Bay Oyster Farm was the first step in ousting agriculture from the park altogether.

As for the Drakes Beach herd, the park service is looking for workable solutions. But a new elk fence along the Inverness Ridge—as ranchers have proposed—-probably doesn‘t qualify. “It would be too easy for the elk to get around,” says Press.

Instead, the park service has been trying to steer elk to where it wants them by sprucing up a section of retired pasture and keeping a pond that had been going dry filled with water. Meanwhile, park staff are also hazing the elk off pastures. There are some promising signs in radio collar data that this approach is working, and the elk are spending less time in the pastures, says Press.

But there’s still the issue of population growth. So in the new plan, the park service is considering a cap on the number of elk in the free-roaming Drakes Beach herd, among other alternatives, according to Gunn and Press. How that might be maintained—professional culling, or convincing CDFW to translocate animals off the seashore, or some other option—is still very much up in the air. No doubt, the conversation with the public won’t be easy, says Press: “I think there are some tough days ahead.”

While this is a national conversation, involving many of the people who regularly visit the popular park, the resolution of the issue may well arise from the West Marin community itself. Amy Trainer, the executive director of West Marin Environmental Action Committee, is one of the rare birds who has straddled the fence lines on this issue. She initiated an ad hoc working group composed of local environmentalists and ranchers (at a recent meeting people from all six dairies showed up) to find some middle ground on the elk and keep the conversation civil. “We’re very solutions focused and it’s been good in so many ways,” Trainer says. “It’s helped heal the community after the oyster battle… We have a great opportunity at Point Reyes to show how protecting national park values and the tule elk population is a success story that can absolutely coexist with small-scale sustainable farms and dairies.”

It’s a hopeful tone, one that places great faith in the West Marin community and its diverse set of voices to sort themselves out—if only they take into account that the elk, wild as they are, will always be elk.