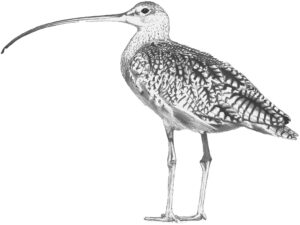

They’re known as peeps for their high-pitched voices. They’re the runts of the Scolopacidae, the shorebird family that includes sandpipers, yellowlegs, willets, turnstones, curlews, godwits, dowitchers, and phalaropes. The aptly named least sandpiper (Calidris minutilla) is sparrow-size and weighs about three-quarters of an ounce (equal to a dollar in quarters); the western sandpiper (C. mauri) is only a bit larger.

Those two species are by far our most common peeps. But it can be a challenge to tell them apart. Westerns tend to forage at the water’s edge, leasts on drier ground, but they frequently overlap and mixed flocks are not uncommon. “Leasts are more likely to be back in the tidal channels, in more vegetated areas,” says Point Blue Conservation Science biologist Dave Shuford. “They tend to occur in smaller flocks and are less prone to flush, more likely to freeze when a raptor goes over.” Both engage in dazzling synchronized flight, often provoked by a passing raptor. William L. Dawson (Birds of California) describes the flight of a western sandpiper flock: “[T]hey weave and twist about, now flashing in the sunlight, now darkening to invisibility, charge and recharge, feint and flee, all as a single bird.”

Both of these tiny birds commute from Arctic breeding grounds. Many end up in San Francisco Bay and other California estuaries for the winter; some continue on to Panama, Brazil, or Peru. Radiotelemetry research in the 1990s mapped the western’s travels. “In the spring, 90 percent of the westerns going north to breed funnel through Alaska’s Copper River Delta,” says PRBO’s Matt Reiter. Males winter farther north than females, so most wintering westerns in California are males. Prior to their migration, westerns lay on muscle and fat and even reshape their internal organs for the journey–about eight days from here to the Copper River, plus rest stops.

For years, scientists thought migrating peeps fed exclusively on small marine invertebrates. Then a Japanese researcher discovered that western sandpipers also consume biofilm, a community of microorganisms dominated by photosynthetic algae: edible primordial ooze. Biofilm, common on mudflats, had been regarded as snail chow at best. But videos showed westerns using spines on their tongues to form it into swallowable boluses. U.S. Geological Survey biologist John Takekawa says biofilm appears to be a supplemental food for northbound migrants. Least sandpipers also have the tongues for it, but no one knows for sure if they eat biofilm.

Peep feeding schedules are tide-driven. Stacy Moskal, also with USGS, says they’ll work nights: “They’re not visual foragers; they use their bills as sensory organs. They’ll forage as long as they can feel something.”

Separating least from western in the field is a challenge, but doing so in winter is a snap compared with sorting out spring and fall plumages, which, as Peter Matthiessen writes in The Wind Birds, “assert themselves in such disorder that no two birds in 10 of the same species look alike.”

For identification, I’ll defer to local birding guru Rich Stallcup, writing in 1988: “The tiny ones that have a short, sharp bill, a blurry brown wash across the breast, and a patterned brown back are Least Sandpipers. . . . The tiny ones that have a slightly drooped bill, are bright white below, and have unpatterned, light gray backs are Western Sandpipers.” Leasts have yellow legs, westerns black, but beware muddy-legged leasts.

In November 2011, observers fanned out across the Bay and coastal California in the third annual Pacific Flyway Shorebird Survey. Western sandpipers have historically been the most abundant shorebird in the survey, with 103,000 tallied in 2008. But local counts over two decades show westerns declining, while leasts have increased. Westerns are also down elsewhere in their range. Reiter says possible reasons include habitat loss (including changes in the Bay of Panama, a major wintering area) and climate change (birds arriving on the breeding grounds too late for spring’s insect bounty). Ironically, some researchers implicate the rebounding peregrine falcon. A Canadian study suggests northbound westerns are spending less time feeding at stopover sites with high predation risks.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch, even if it’s biofilm.