Point Blue Conservation Science marine ecologist Jaime Jahncke has been surveying the California coast every year for the last 12 years with staff from Cordell Bank and Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuaries. He has never seen anything like what he saw in 2015. In one of the strangest ocean years ever recorded, neither has anyone else.

“I can’t truly give an explanation of what is going on right now,” Jahncke said.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

El Niño: Beyond the Hype

Bay Nature goes beyond the headlines to explore what the strongest El Niño in recorded history might mean — or not — for Northern California. We’ll post new articles here throughout the fall and winter.

This series has been funded by donations from Bay Nature readers. Please help us by sharing our work, or donate today to support our mission to explore the natural world of the Bay Area.

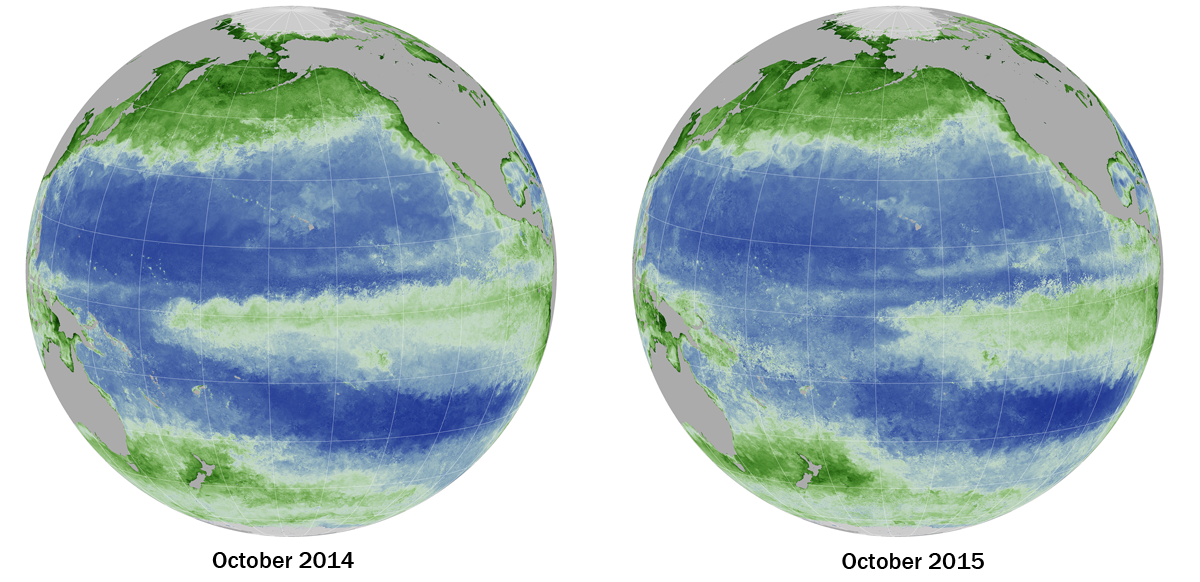

El Niño events in the past changed California’s marine ecosystem, but 2015 was different – in part because the Pacific Ocean was extraordinarily warm for months before the warm tropical water driven across the Equator and up the coast by this winter’s record-strength El Niño had even arrived. “There are two phenomena, the warm ‘Blob’ and El Niño, which are different,” said John Largier, a coastal ecologist at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab. “They have similar symptoms, but the causes are different. How they interact we don’t know.”

Point Blue’s seabird monitoring station in the Farallon National Wildlife Refuge recorded its warmest seasonal sea surface temperatures this nesting season since 1992, with 2015 joining 2014 as two of the four years ever recorded with a seasonal average ocean temperature above 55 degrees. The northeastern Pacific has been abnormally warm for two years – this fall was the hottest the ocean basin has ever been recorded — and because the slug of warm El Niño water will arrive soon, it’s likely to stay above average for a while.

For marine life, the changes start at the bottom of the food web. In the summer and fall, Jahncke said, scientists on the Applied California Current Ecosystem Studies (ACCESS) cruise typically use a small 3 feet hoop net to pull copepods and plankton out of the water. This summer free-swimming gelatinous zooplankton were so thick in the water they clogged the nets, and researchers couldn’t get the nets over the side of the boat until they’d drained. Many of those plankton were doliolids, free-swimming tunicates associated with tropical waters, said Catherine Davis, a UC Davis graduate student who has spent the last four years monitoring California plankton. And just as they’d arrived, they disappeared: for a brief window in September when the cruise went out again, Jahncke said, sea surface temperatures had dropped back to normal, and the doliolids had disappeared.

Davis focuses in particular on foraminifera, sand-grain-size zooplankton that also had an unusual year. Foraminifera are well-studied around the world, so researchers have a pretty good idea of what species to expect in what places. In the last three years Davis has generally seen a range of species that seems to range southward from Oregon to California. But this year currents brought in tropical species seeking homes in the warming Northern California waters. The new plankton are as much as three times larger than the regular California residents, Davis said. “This is a disruption of what we would have expected based on findings in previous years,” Davis said in an email. “We are still trying to understand the food web implications of these changes.”

NOAA fisheries ecologist John Field has conducted a separate research trawl off of Monterey every summer since 1983, and reported a similarly unusual summer. Pelagic tunicates like the doliolids that clogged the ACCESS nets were at “extreme to record high levels,” according to a paper written by Field and his NOAA colleague Keith Sakuma. Field reported tropical species, “El Niño harbingers,” flooding into the warm waters of Northern California – with record high counts for pelagic red crabs, California spiny lobster, a pelagic larvae called phyllosoma, and a subtropical krill species called Nyctiphanes simplex. He also reported catching a number of species for the first time ever, including a pelagic octopus called a greater argonaut, slender snipefish, and a subtropical krill called Euphausia eximia. “The 2015 survey was highly unusual,” Field and Sakuma wrote, “in that species characteristic of all three of what might very generally be considered nominal states were encountered in high abundance throughout this region.”

In September, the ACCESS cruise caught a pelagic red crab at Cordell Bank, the first they’d picked up since 1985. A month later, thousands of red crabs washed ashore in Monterey Bay, the first mass stranding there since the strong El Niño in 1983. “We have a lot of things, going forward, to piece together,” Jahncke said.

Field’s NOAA survey also highlighted a changing abundance of fish species, with higher numbers of young rockfish and market squid, and lower numbers of sardines and anchovies. Those trends started in 2013, the report suggests, meaning El Niño’s not to blame. “Such shifts,” the report continues, “have important implications for higher trophic level species such as seabirds, marine mammals, salmon, and adult groundfish.”

And that’s where the changes many of us have seen come in. Starving marine mammals, poisoned crabs, dead birds washing onto central coast beaches by the thousands – it’s been a weird year at the top of the food chain, too. Jahncke says researchers on the ACCESS cruises also spotted Guadalupe fur seals and common dolphins, both more frequently seen off the coast of Baja and in tropical waters.

While warm water and a changed plankton distribution typically mean a straightforward bad year for seabirds, Point Blue observations at the Farallon Islands suggest that 2015 was more complicated. Overall, 2014 and 2015 were surprisingly good years for birds on the Farallones. Perhaps, Jahncke says, that’s because of a strange dichotomy in the ocean behavior: for the first half of the bird breeding season, the upwelling was strong and the food web more normal. But by mid-summer – when the research cruises were out — it had weakened, leading to less food in the water.

Cassin’s auklets and common murres , for example, have suffered back-to-back years with unprecedented mass die-offs. Jahncke said he went camping in Santa Cruz this fall when more than 50 washed-up dead common murres covered more than a mile of beach. The auklet’s second nesting failed completely in 2014 and birds didn’t attempt a second brood in 2015, and the productivity was the lowest it had been in six years. Yet the birds had a successful nesting at the Farallones, and high success rate for those broods, resulting in an “overall productive season,” according to a seabird report prepared by Point Blue.

According to the Point Blue paper, seabird reproductive success at the Farallones was “much greater” than in previous El Niño years, but the warm conditions undoubtedly had an effect on the size of the breeding populations. Point Blue reported the lowest breeding population of Western Gulls in the past 45 years of observation – but the gulls also were the only species to have higher reproductive success than in 2014.

The warmer waters also brought unusual species to the islands. Normally tropical brown boobies were seen in record numbers, while researchers saw two species – wedge-rumped storm-petrel and kelp gull — for the first time ever at the islands.

Jahncke wasn’t in California for the last strong El Niño, in 1997-1998. But, he said, “I’ve seen the numbers, and the data, and the impact it had.” In 1998 Jahncke was working for a Marine Fisheries Research Institute in Peru, which also has an upwelling-driven ecosystem that’s thrown into chaos by El Niño. One of the things he learned in that event, he says, is that even in a warm year there are some refuge areas that stay relatively cold, where the food web can continue more normally. There’s been a parallel this year, he suggested, with the “Blob” of hot water off the Pacific Northwest and the El Niño-driven hot water at the Equator leaving pockets of cool water in a few places in Northern California, where a huge number of larger marine mammals have sought refuge — perhaps explaining the unusual number of whale sightings close to shore in Monterey Bay and just outside the Golden Gate.

Those refuges, said coastal ecologist Largier, might be more seasonal than spatial. The upwelling that drives so much of California’s marine food web productivity remained fairly normal at its peak in the late spring and early summer – but as soon as it weakened, it weakened rapidly and dramatically. “It seems like in this area the upwelling can hold its own against the warm water, at least in the peak of the upwelling season,” Largier said. But, “it’s like blowing against water to keep it away from you and then you stop.”