Twenty years ago this month, I wrote in a journal: “Everything changed the other day. A small town doctor came back into the room and stared at me. ‘I have to do something that I’ve never had to tell a patient. Your test came back positive. You are H.I.V.+.’”

I’m so co-dependent I remember immediately comforting him for having to have done that. I drove to my parents’ house and will always remember the terror in my mother’s eyes after I told her. “We’ll get through this, Liam,” she said.

I drove back to my apartment in Benicia and remember picking up … the National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Butterflies as a way to handle the tsunami mudflow I was now traveling in. I can’t really explain why I picked it up. Butterflies hadn’t really taken ahold of my life yet. I think something about the order, the taxonomy, their beauty … it seemed even larger and more important than the news I’d just been handed. I also wrote: “I’m not quite sure where all of this is going. As the virus progresses, I hope it…can’t get to…my spirit. I …hope.”

Amazingly enough, I acquired the condition right when it was changing from a death sentence to a chronic illness. I start with this story because, please, do not feel sorry for me. I’ve been doing fine since I started the cocktail of daily pills soon after the diagnosis. A friend of mine at the time said, “First of all, welcome to the Club and secondly, the disease is set up for the indigent and the wealthy and, unless you are planning to go out and win the lottery tomorrow, I advise you to go … make yourself poor.”

A great deal has changed in the management of HIV since he said that. It’s still a rather complicated bureaucracy to negotiate but what I’m about to say might be difficult for many to understand: the virus gave me … butterflies. And I don’t regret a second of hosting it.

I used to be a professional stage actor. I studied, acquired skills and entered the union at 22 years old. My secret weapon: a double-gauge shotgun singing voice. When I was at an audition, I assuredly asked directors: “Where do you want me to point this thing?” (Confidence is different than arrogance.) I had luck. Lots of luck and a career than many young actors would have dreamed of. I landed a Broadway gig eight days after hitting that island – a dream many never fulfill. Something, however, was missing: drive. Theatre was something I just did. Almost no fulfillment. Performing in beautiful, cavernous regional theatres to folks packed to the rafters then home alone on a bus.

And then in 1999, a Western Tiger Swallowtail (P. rutulus) flew into the yard.

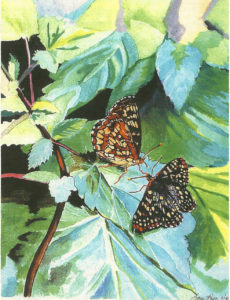

I was living off the Duboce Triangle in San Francisco and I went down the back staircase and got incredibly close to it while it fed from a fuchsia cosmos flower. I ran back upstairs and got some paper and started sketching — something I hadn’t done in many years. I had no idea my life had just taken a 180-degree turn. I went down a rabbit hole that day in the yard and I’m still … down there? I joined the Lepidopterists’ Society soon thereafter. Started to keep an intense journal. I found myself painting places where the butterflies were, THEN inserting the butterflies — sort of a Field Guide in reverse.

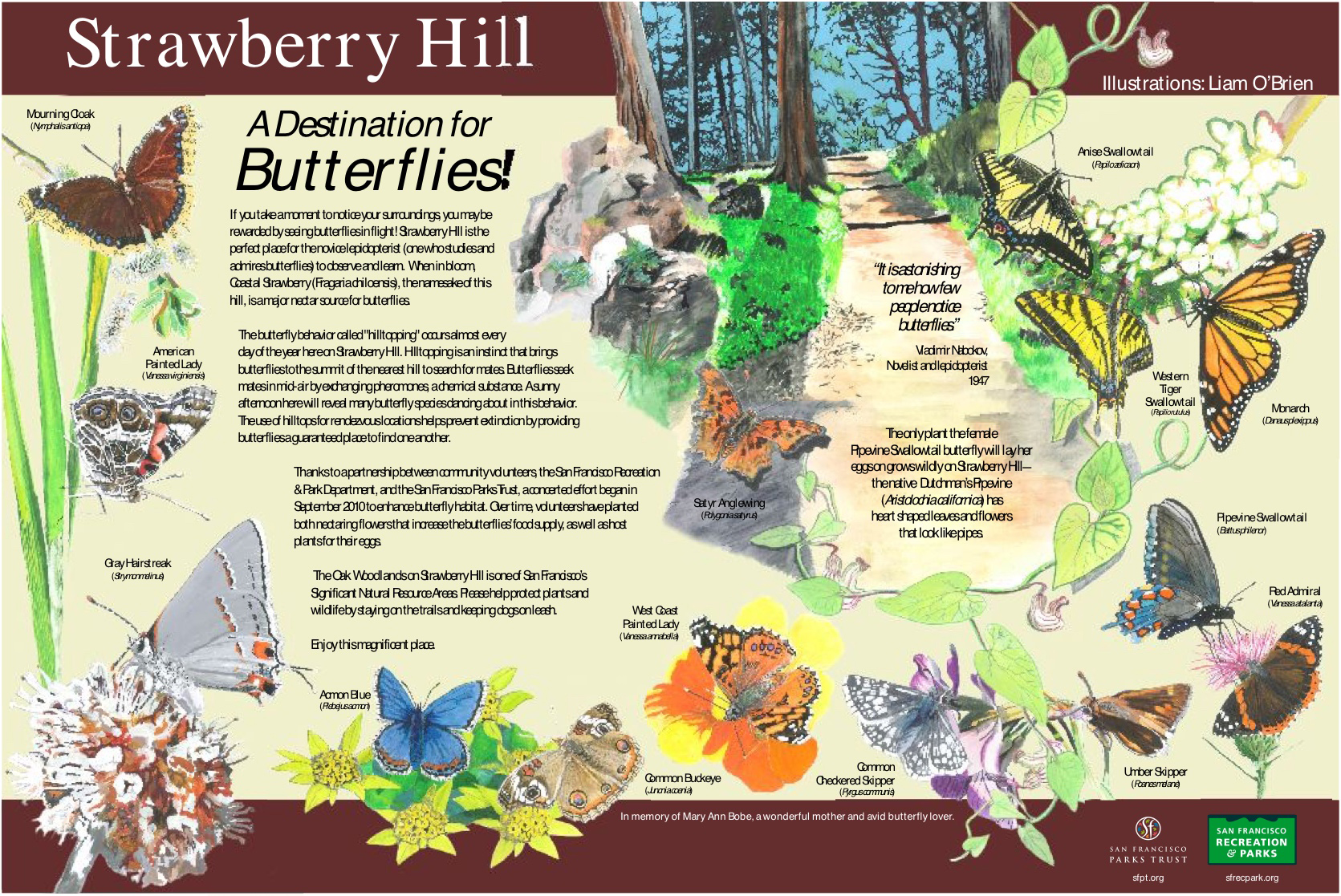

I’d heard Jerry Powell say once at a lecture, “Learn Where you Live.” And I remember thinking, “God – San Francisco. What a crap hole for butterflies.” But no one had inventoried the city in decades so … I decided to do that. That was 2004.

Then I started to consider an idea for something that we might be able to do to help a small, emerald green butterfly still hanging on in the Upper Sunset district. The Green Hairstreak Project, a streetscape wildlife corridor of host and nectar plants, was born with the guidance of Peter Brastow and Amber Hasselbring of Nature in the City. Other ideas for urban conservation continued. I somehow became the go-to person for this group of creatures. My old theater training of dispassionate objectivity as an actor began to synthesize with my new world: not only do I find butterflies enthralling (who doesn’t, right?) but I’m equally interested in our relationship to these insects.

I’ll be writing about butterflies, and what we think of them, once a month here. I want to use this space to crowbar back a lot of the emotion our species has projected onto them. It’s hard to really discuss butterflies sometimes with other humans. It kinda seems like folks don’t want to go any further than a Hallmark card. Butterflies are so bogged down in myth and misinformation, I’m sometimes surprised they can fly at all.

I want to take all of us further with butterflies here. We have a great deal of paint build-up to strip away with the subject and that’s gonna take some corrosive solvents — my words. My main aim is to return them to a place they’ve been strangely removed from: wildlife. These are living, wild insects, not pretty objects. (Or, as Jeffrey Glassberg, president of the North American Butterfly Association calls them, “party favors for the human circus.”)

And now for the hypocrite part: I love the beauty of butterflies. I love the actual detail of real butterflies, not so much the fantastical representation of them. But that’s just me.

The number one things folks with HIV are supposed to stay away from is stress. It eats the immune system’s T-cells like Pac-Man eats those dots. What could be less stressful than watching a butterfly? How ironic is that?

The virus has connected me to nature in a profound and surreal way: I host a deadly parasitic-like thing within me just like almost all butterfly larvae do (butterflies co-evolved with parasitic wasps and flies — that’s not a bad thing, folks. That just … is.) I take medication to keep it from busting out of me like that alien out of John Hurt’s chest.

The World of Butterflies. And HIV has been a…good tenant through the years: low-key, doesn’t party ( anymore…) and pays its rent on time.

And no, I don’t think it’s touched my spirit.