What are some green things to see in nature in the Bay Area?

If the prospect of yet another American St. Patrick’s day replete with dye-tainted beer, more-Irish-than-thou co-workers, and weird Irish stereotypes has got you down, here are several green creatures to populate your thoughts. We guarantee they have little to nothing to do with saints, Guinness, kissing, ophiophobia, or other disappointments.

Pacific Green Sphinx Moth (Proserpinus lucidus)

When you think of moths you might envision anonymous monochrome flappers at summer porch lights. With its verdant vestiture, yellow and mauve trim, and a preference for flying in January, the Pacific Green Sphinx will make you think again. Look for this moth at lights in January and February in areas where its host plant, elegant clarkia, grows in abundance, or seek out its hulking and, sadly, less-green caterpillar a few months later when clarkias are budding.

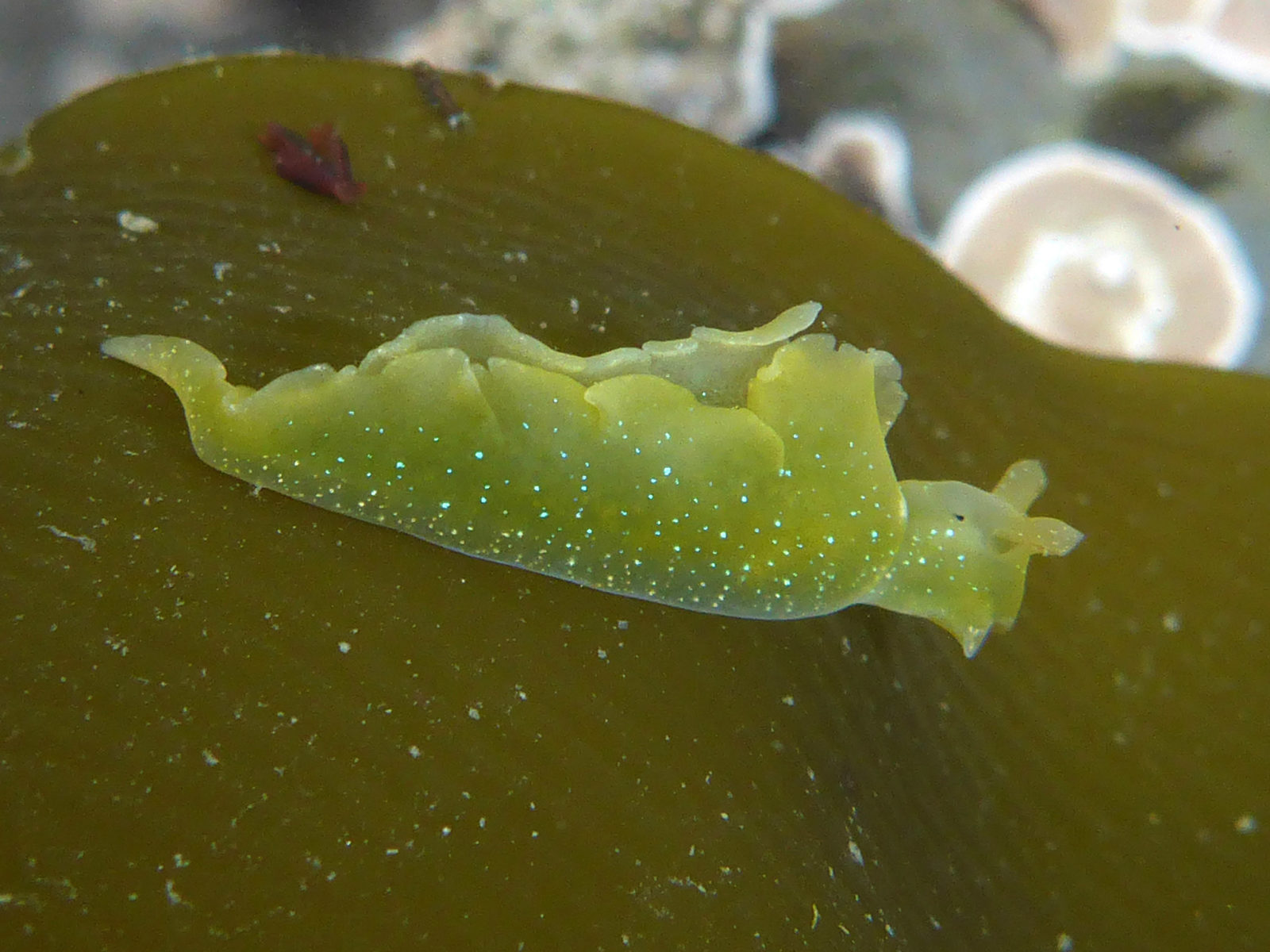

Hedgpeth’s Sapsucker (Elysia hedgpethi)

No, not the beaked marauder that sups on the sap of trees. This is a slug, a glorious, emerald sea slug bedazzled with blue dots that prefers the “sap” of marine algae in San Francisco Bay. It’s hard to imagine a creature more different from a woodpecker than a sea slug, but it gets weirder: Hedgpeth’s Sapsucker can maintain the chloroplasts of its chosen repast in an active and photosynthesizing state for days, creating a meal that keeps on feeding. Even wilder, relatives of this slug have integrated algal genes into their own genome, making them part animal, part plant! We don’t know if the same is true of Hedgpeth’s Sapsucker, but it seems likely. And if that wasn’t enough, this slug is named after Joel Hedgpeth, the pioneering Bay Area naturalist and conservationist perhaps best known for successfully fighting plans to install a nuclear power plant at Bodega Head. Look at this slug and soak in the history, both human and non-human.

Michael’s Rein Orchid (Piperia michaeli)

Described by UC Berkeley’s first botany professor, Edward Lee Greene, way back in 1885, the green spires of this California endemic have been stunning California’s flower aficionados ever since. Look for this rare orchid in late spring and early summer among coastal dunes and in mixed oak woodland and chaparral, and take note of its signature fat lower lip, which distinguishes it from similar green rein orchids like the denseflower rein orchid (Piperia elongata).

Lungwort Lichen (Lobaria pulmonaria)

While many lichens achieve a sort of jaundiced verdigris at best, when lungwort gets wet it’s about as green as green can be. Like all lichens, lungwort is a fungus that practices agriculture: it cultivates and sustains photosynthetic organisms to produce sugars it needs to survive, and one of those crops is a green alga, which lends this lichen its lush hue. Lungwort actually sustains another “crop” of cyanobacteria in discrete structures called cephalodia, and these bacteria fix atmospheric nitrogen so the fungus doesn’t have to derive it from its substrate. Despite this self-sufficiency, lungwort is very sensitive to air pollution, so if you happen to spot it on the bark of a tree, you know you’re breathing clean air.

Anna’s Hummingbird (Calypte anna)

These constant garden companions often draw the eye with a shock of brilliant amethyst when the sun catches the feathers on the head of a male, but they are no less remarkable for the scintillating tourmaline hue of the wing and back feathers of both sexes. What is less obvious about these most obvious of birds is that their color is not due to pigment but to the minuscule, refractive structure of their feathers, which do not absorb ungreen wavelengths of light but cancel them out through destructive wave interference. Green wavelengths are not merely reflected but amplified, creating a green that borders on the uncanny.

Parrot Mushroom (Gliophorus psittacina)

The parrot mushroom, it must be admitted, adopts many colors over the course of its brief appearance above ground, but its fresh green hue is what sets it apart from its fellow waxy caps, which vary from brilliant reds and yellows to subtle pinks. Colors in mushrooms are, at best, mysterious. Bright colors may have evolved to ward off would-be diners, or they might have evolved to perform the opposite task and attract said diners so they might spread the fungi’s spores far and wide. Where does this leave our slimy, green little neighbor? As with so much about mushrooms, there remains much to discover.

California Stick Insects (Timema sp.)

You could live your whole life in California and not realize we have our very own and very weird group of stick insects, one so bizarre that it is on a different evolutionary branch than all other stick insects. But, one has to ask, would such a life be worth living? Aside from being more Californian than any of us, these stick insects are worth knowing for their strange evolutionary history. Many of our species occur in closely-related pairs, where one species reproduces via sex and the other is 100% ladies who lay eggs without bothering with the diminutive, clingy, sperm-filled accessories their cousins seem to tolerate (males are, in fact, smaller, sometimes much smaller). Each species in these pairs usually uses the same host plant, but occupies a different geographic range. Our Bay Area species, however, are all the color of leaves, and since they tend to reside on leaves, they are mighty tough to spot. They are so cryptic that entomologists often collect these creatures via the extremely precise and scientific practice of beating a shrub with a stick, in the hope that insects will just fall out. It is surprisingly effective, both for collecting insects and convincing your fellow humans to avoid you entirely, the dual goals of many a naturalist. Keep an eye out for Timema in the spring and early summer in areas where native plants are plentiful.

California Sister (Adelpha californica)

Yes yes, these black-and-orange beauties show not a hint of green as adults, but as caterpillars they are a perfect leafy green. Never seen one? You’re not alone, despite the fact that these butterflies are ubiquitous wherever their oaken hosts have taken root. Given that only a fraction of caterpillars survive into adulthood, there must be a veritable army of these verdant beasts munching away in the canopies we happily hike beneath, yet few of us ever see them, even those of us who spend a great deal of our time gazing intently at leaves. Why is that?

Ask the Naturalist is a reader-funded bimonthly column with the California Center for Natural History that answers your questions about the natural world of the San Francisco Bay Area. Have a question for the naturalist? Fill out our question form or email us at atn at baynature.org!