In August of 1962, Pierre Saint-Amand, a geophysicist at the China Lake U.S. Naval Ordinance Test Station, left Los Angeles and drove homeward across the Mojave Desert to that vast military base, all sagebrush and alkali in the middle of nowhere. For mile after mile the pale desert slipped away to either side. The geophysicist turned up the radio. KPFK was broadcasting a program produced by its sister station, KPFA, up in Berkeley. The reporter, Joan McIntyre, was describing a PG&E proposal to build a nuclear power plant at Bodega Bay on the San Andreas Fault.

The fight to kill this project would prove epochal in the history of environmentalism, as that new movement was not yet named. The protagonists, many still alive today, lived this history intimately yet have trouble picking the point at which fate stepped in. The tide of battle turned, but when? They offer this Mojave moment as one possibility: in the middle of the desert, a road-weary geophysicist is jarred wide awake by what he hears on the radio.

The electric utility up in Northern California! They planned to site a giant 325-megawatt reactor, the biggest nuclear generator in history, atop the San Andreas, the slip-strike fault that had destroyed San Francisco in 1906!

Two years prior to his desert drive, Saint-Amand, on loan from the Navy to the State Department, had been in Chile, helping the University of Santiago set up a graduate school in geology, when he witnessed the biggest earthquake ever recorded. On Sunday, May 22, 1960, at 3:11 in the afternoon, the Valdivia Earthquake, a 9.5, struck Chile’s south-central coast. It shook the ground for approximately ten minutes with violence unprecedented since the invention of the seismograph. Long stretches of coastline subsided, sinking under the sea. Mountains fell apart. Huge landslides and debris flows roared down Andean slopes to alter the courses of some rivers and to dam others, creating new lakes. In Chile, Saint-Amand illustrated his fact-finding with his camera: photos of slumping buildings, twisted railroad tracks, coastal towns shattered and then flooded by the one-two punch of earthquake and tsunami. His pictures make a stark record of catastrophe. He had no trouble imagining the consequences on the San Andreas if the Big One—or even a little Big One, like the 1906 quake—seized the containment vessel of a nuclear reactor and shook it like a rat. On reaching home at China Lake, Saint-Amand called David Pesonen, the young man leading the opposition to the nuclear plant. He volunteered to do whatever he could to help.

Bodega Head is a windswept, nearly treeless promontory that shelters, in its lee, Bodega Harbor, the village of Bodega Bay, and the mouth of Bodega Bay. The headlands of the promontory see dense fogs in summer, heavy surf in winter, and a profusion of wildflowers in spring. Offshore, the blows of gray whales peak in January as the whales head south to their warm Mexican lagoons to give birth, and then again in March, on their migration north to their feeding grounds off Alaska. Overhead, migrating raptors and great flocks of ducks and shorebirds follow similar routes by air.

The headland is made of granite. The rock facing it to the east, on the far shore of Bodega Harbor—which is to say the opposite side of the San Andreas Fault—is softer, more chaotic, and of entirely different origin. The formation over there, on the mainland, is the Franciscan Complex: sandstones, limestones, shales, greenstones, cherts, serpentine, blueschists. Bodega Head bears no resemblance. Like its sister formation, the Point Reyes Peninsula immediately south, the headland is a wandering terrane, part of the granitic Salinian Block, a sliver of the North American Plate sheared off and captured by the Pacific Plate. Both the peninsula and the promontory have been sliding north up the western side of the San Andreas for many millions of years. In April 1906, Bodega Head took a particularly sharp lurch toward wherever it is going.

In the 1950s a thriving commercial fleet fished out of Bodega Harbor: crab, rockfish, salmon, steelhead, halibut. The little town of Bodega Bay had nothing of the boutique fishing village to it, no spas or B&Bs or destination restaurants. It was a gritty blue-collar place. Its dairymen worked the rangeland to the east, and its fishermen worked the California Current to the west.

The biggest landowner on Bodega Head, and among the first residents to learn of PG&E’s plans for the promontory, was one of these grounded people, a big, craggy widow named Rose Gaffney. Rose had arrived from Poland by way of Canada around 1911. At 16 she had gone to work for the Gaffney brothers, who owned much of the middle of the promontory. Pregnant and engaged to marry one Gaffney, she lost him on the day before the wedding to gunfire in a brawl at a Bodega bar. Improvising, she married the other, Bill Gaffney, the brother of her murdered fiancé. It was a happy marriage. Then in 1941 Bill died, too. Rose had run out of brothers and she never married again.

The Widow Gaffney loved the land she had inherited. She knew every rise and indentation of Bodega Head. It was an intimacy reflected best, perhaps, in the enormous lode of Native American artifacts she gathered there. A surface hunter—Gaffney never dug—she spent 50 years combing Bodega Head and the shores of Bodega Harbor: cobble choppers, elk-antler tools, spear points, arrowheads. The Coast Miwok were masterful knappers of obsidian, and the black, crescentic, two-foot-long blades they left at Bodega are surely among the most beautiful objects ever made, as exquisite as Gaffney herself was rough-hewn.

Underneath Gaffney, imperceptible even to her, Bodega Head was migrating northwest about two inches a year—the rate at which a fingernail grows. The science of plate tectonics had not yet been fully born, and early arguments for the theory had not reached the textbooks, much less the Gaffney spread. Gaffney, fiercely protective of her creeping acres, was given to patrolling her borders with a baseball bat. When two PG&E men in suits arrived with offers to buy, she minced no words and sent them on down the road. The warfare that followed was asymmetric, of course. What a powerful electric utility has, and a rural widow lacks, is a big legal department and the power to condemn property by right of eminent domain.

Dr. Joel Hedgpeth, director of the Pacific Marine Laboratory at Dillon Beach, at the southern end of Bodega Bay, was another local to get wind of PG&E intentions early. Hedgpeth’s specialty was the Pycnogonida, the sea spider, but his interests ranged far more widely than that. He had become one of the fathers of western intertidal ecology. And one of Hedgpeth’s perennial tasks was the revision of successive editions of Ed Ricketts’s classic on that topic, Between Pacific Tides. It was this narrow but rich province—the zone between high tide and low at Bodega Bay—that most concerned Hedgpeth. The University of California had identified Bodega Head as the best site in northern California for a marine research station. The same characteristic that made Bodega Head ideal for a marine lab—peninsularity, with a rocky surf-zone habitat on the ocean side and a shallow estuarine habitat on the bay side—made it ideal for a nuclear plant. A reactor core, if it is not to go critical and melt, requires great volumes of water to moderate the internal heat of fission. A conventional steam plant, coal-fired, would be a bad enough neighbor for a marine lab. A nuclear plant, discharging hot effluent into a cold-water marine ecosystem, would be the neighbor from hell.

The university’s main contender for the headland was the California State Parks Commission, which had long seen Bodega’s cliffs and beaches as potential parks. Abruptly now, with the entry of PG&E, both the university and the parks people abandoned their plans. Joel Hedgpeth had no hard evidence as to why. But it was not hard to guess. The university, since the Manhattan Project, had enjoyed an intimate and profitable relationship with the atom, both wartime and peaceful. In the 1950s a huge chunk of UC’s sustenance came from managing two national weapons labs. A former UC chancellor, Glenn Seaborg, was now chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. PG&E was politically powerful. The dots were there to connect.

In 1958, when PG&E first announced its plans for a power plant at Bodega, it claimed not to have decided between coal and uranium. Hedgpeth doubted that the company had ever wrestled with any such uncertainty. Shortly after the PG&E announcement, he went public with his opposition to the plant. For a time he had little company; then in late 1961 the company finally announced that the plant would be nuclear and things started heating up.

In February of 1962, Harold Gilliam, the environmental reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, wrote a column, “Atom vs. Nature at Bodega Bay,” that lamented the loss of prime coastal parkland to atomic power. Karl Kortum, founder of the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, wrote a widely read letter of protest to the editor of the Chronicle. These two newspaper items caught the attention of a regional public beyond Sonoma County. Shortly thereafter, Hedgpeth, Gilliam, and Kortum founded the Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor (ncapbhh). They set about the daunting task of stopping the juggernaut of PG&E.

Earlier that same year, two years after his graduation from the School of Forestry at the University of California, David Pesonen was hired by the Sierra Club. His title was Conservation Editor, but he was never quite sure what his actual job was. His degree was in forestry, so he became the Sierra Club spokesman at Forestry Board meetings.

Then one day the Sierra Club’s first executive director, David Brower, my father, called Pesonen into his office. He handed the young man two clippings: Hal Gilliam’s column on Bodega and Karl Kortum’s letter of protest. “In his column, Gilliam treated it as just a lost cause,” Pesonen recalls. “But Dave said, ‘Well, go look into this. See what you think.’ Again, it was the jack-of-all trades kind of thing. I was hired for forestry stuff, and now Brower had me doing nuclear energy.”

Pesonen knew nothing about nuclear energy, or Bodega Bay, or the plant that PG&E wanted to build there. He decided to go to the source. Departing the Sierra Club office on Bush Street, he walked a couple of blocks down to PG&E headquarters at 245 Market Street. “Naively,” he says. “This was on my own initiative. I went up to the engineering department, on the tenth floor. It was noontime. There was just a secretary there. I said, ‘I’m interested in the Bodega case; do you have a file on it?’ And she handed me this file.” Combatants in the Bodega Bay fight offer this moment—the gift of the file—as another possible tipping point in the campaign against the nuclear plant.

“Can you imagine something like that happening today?” Pesonen asks. “She didn’t think there was anything wrong with it, just handing me the file. So I started going through it. I saw a whole lot of correspondence back and forth between the public affairs department of PG&E and the board of supervisors of Sonoma County and other public officials. There were all these indications that PG&E had local government in their pocket. My antennae started to go up. So I copied a lot of this, in handwritten notes. They didn’t have copying machines in those days.”

There was little organized opposition, as yet, to the nuclear plant. The NCAPBHH had grown a bit, with the addition of Karl Kortum’s wife, Jean, and his brother Bill, a Sonoma veterinarian with connections among the county’s dairymen. Berkeley professors Joe Neilands and Thornton Sargent threw in, along with several locals. “One was Rose Gaffney, the owner of the property that PG&E was condemning,” says Pesonen. “She was a colorful old character. Sort of looked like Bodega Head. We were just a motley group.”

The Hal Gilliam and Karl Kortum Chronicle pieces had created a stir, and the state Public Utilities Commission responded by reopening the licensing procedure and holding hearings in March 1962. “Their purpose obviously was to just let the public vent,” says Pesonen. “And then have PG&E get on with the business that they were determined to do anyway. So they held these hearings and they were the most chaotic hearings I’ve ever seen. Completely wild. Anybody in the audience could stand up, and call to be recognized, and then cross-examine the witness.”

To the hearings Pesonen brought a black briefcase with metal snaps on top. Inside were the notes he had cribbed from the PG&E file. On the basis of these longhand excerpts, he and his faction had leveled charges of corruption against the utility but he had not yet disclosed his source, and at the hearings he waited for a dramatic moment to do so. The PG&E lawyers, in cross-examining him, seemed to sense intuitively that they should avoid this subject. But Pesonen had intuition, too. “I anticipated that they might not ask me, so I planted a question in the audience with a member of our crew, Tony Sargent.” If PG&E failed to do so, then Sargent was to stand and ask, “How do you know all this?”

The moment came. Sargent stood. “What authority, what basis, do you have for these accusations?” he demanded.

Pesonen pushed his briefcase close to his microphone on the dais. He popped the snaps. The twin clicks, amplified, echoed across the hall like rifle shots. Leaning into the microphone, he described how he had come into possession of the file. “You should have seen the flurry of activity at the counsel table for PG&E,” he says. “Somebody ran out and got on the phone. Total dismay and chaos on their side of the room. I knew we’d hit a nerve.”

Then, on November 10, 1962, the NCAPBHH held a public meeting in Santa Rosa to gather recruits. If the group was going to stop PG&E, they would have to grow the grassroots resistance well beyond the few blades of themselves.

There was a big turnout, fortunately. About 200 people filed into the hall. It was a crowd very different from any gathering you would see in Santa Rosa today; Sonoma County was much less populous and more rural then. “It had a very interesting mix of people from the whole political spectrum,” recalls Doris Sloan, then a Sebastopol housewife, in attendance that day. But the session did not go well initially, Pesonen concedes. “I was the emcee. I could see people starting to get restless. Some started to drift out. We were losing our audience.”

Doris Sloan saw it the same way. “The room was pretty packed,” she remembers. “There were a lot of speeches. Joe Neilands, the biochemist, got up and talked, spouting numbers. And David Pesonen spouted information. There were a lot of speakers all telling us why we shouldn’t have a power plant there. It was getting very tedious and not very exciting.”

The meeting was thrown open to public discussion. Dr. Allen Butler of the California Department of Public Health asked whether PG&E, in addition to a reactor at Bodega, intended to build a fuel processing plant—a considerably more hazardous operation. Pesonen answered that PG&E had not been forthcoming with details. Nobody on the panel knew the answer. But earlier he had spotted Colonel Alexander Grendon at the back of the room. Grendon, whose specialty had been chemical and radiological warfare, was retired from the Army and now serving as Governor Pat Brown’s “Coordinator of Atomic Energy Development and Radiation Protection.” He tossed Dr. Butler’s question to Grendon.

No, the colonel answered, PG&E did not intend to build anything but a reactor. The panelists began asking him questions. First the tone of his answers, and then the content, brought the audience back to life. Listeners who had been slipping out filtered back in and took their seats again.

In response to a question from Pesonen, Grendon explained AEC procedure. “The hearing examiner will listen to nobody who is not qualified to speak,” he said. “The general public will not be permitted to testify because they will not be able to demonstrate the expert competence that will be required.”

Was it true, Pesonen asked, that an AEC witness, besides having to prove technical competence before the AEC examiner, in some situations had to be represented by counsel? Grendon denied it. “No,” he said. “Let me set the record straight on that. You don’t need to be represented by counsel, and any statement you make will be received. The question is, what will follow from its being received.”

“You mean, will it be listened to?”

“You will be heard. I simply cannot predict how much effect it will have on the ultimate result. I think in most cases it will have relatively little.”

The crowd grew increasingly restive. It is curious how democracy can doze off and then suddenly thrash wildly awake again. Colonel Grendon, for his part, seems to have grasped that insurgents were outflanking him, but he was incapable of adjusting his tactics.

“People got up and started shouting, they were so angry,” recalls Pesonen. “It became just a hell of a meeting.”

Some combatants in the Bodega fight pick this as the decisive moment. The tide of battle, they suggest, turned less from any clever ambush by their own side; rather, the colonel fell victim to his own friendly fire. Flipping the lever of his M14 to full automatic, Grendon riddled his own boots.

“It was like a matador waving a red cape,” says Doris Sloan. “You don’t tell the citizens in the early sixties in Sonoma County not to be concerned about their environment and their safety and the health of their kids. You don’t tell them to let the government and scientists make decisions for them. That was the catalyzing moment. Not just for me, but for many others in Sonoma County. We decided we’re not going to let Grendon and PG&E tell us how to live our lives. I was so outraged. I get angry just thinking about him standing up and telling me to keep my mouth shut. And the next morning at dawn, literally, I was on my way to a Quaker meeting in Berkeley and I knocked on Dave Pesonen’s door. Woke him up, as I remember. I said, ‘Here I am, what can I do?’”

Mrs. Sloan became Sonoma County coordinator for the ncapbhh. Her job was to rally the troops and keep them informed. She arranged meetings, scheduled interviews and speaking engagements, wrote newsletters, put out information packets developed by the association. She worked out of her house. Three of her four kids (“we all had four kids in those days”) were in school, which freed up a few hours each day. She spent much of her time on the phone.

The NCAPBHH campaign gained momentum. The association launched a recall campaign against Sonoma County supervisor E. J. Guidotti, accusing him of colluding with PG&E. Picnics had become the main organizing and recruiting tool. The association published a pamphlet describing how radioactive fallout is concentrated by grazing cows and ends up in milk. They knocked on doors and passed out leaflets. Sonoma State College students staged a sympathy march. Musicians, for some reason, were drawn to the campaign in disproportionate numbers. The folksinger Malvina Reynolds wrote and sang antinuclear songs for the opposition. Lu Watters, a trumpeter who had played New Orleans jazz in San Francisco, became a staunch ally.

“It was Lu’s wife, Pat, I think, who came up with the idea for the balloons,” says Doris Sloan. “In the Bay Area on most afternoons the winds pick up off the ocean, blow east, and cool us off. Well, Pat had the idea for a party up on Bodega Head, on the bluff above the reactor pit at Campbell Cove. Wouldn’t it be fun to take some helium-filled balloons and release them, to show ordinary people which way the wind blows from the plant?”

On Memorial Day of 1963, around 300 people and a flotilla of helium balloons converged on Bodega Head. Lu Watters lured an old friend and colleague, the jazz trumpeter Turk Murphy, from his normal venue in San Francisco, Earthquake McGoon’s. The folksinger Barbara Dane sang a song written for the occasion, “Blues Over Bodega.” As Bodega Head rocked, the protesters released 1,500 helium balloons. Attached to each one was a tag: “WARNING! This balloon could represent a radioactive molecule of Strontium-90 or Iodine-131. It was released from Bodega Head on Memorial Day 1963. PG&E hopes to build a nuclear reactor plant at this spot, close to the world’s biggest active earthquake fault. Tell your local newspaper where you found this balloon.”

The balloons blew all over the dairy country of West Marin and Sonoma County. Ranchers stooped in their pastures to turn the tags over—“Strontium-90, Iodine-131”—in rough brown hands. Balloons blew into downtown San Rafael and one landed in the Civic Center fountain. Regional newspapers featured the stunt, and radio stations downwind of Bodega were besieged with calls.

In April 1963, Pierre Saint-Amand, the Navy geophysicist, arrived to investigate the geology of Bodega Head. It fell to Doris Sloan to show him out to the site. It was a rainy day. The two drove around the harbor on Tidelands Road, which pg&e had constructed out to the project. The site was fenced and guarded, and on the drive out, Sloan and Saint-Amand discussed the problem of getting in. If necessary, Saint-Armand said, he would show his credentials as a government scientist. He pulled out his wallet for Sloan’s inspection. The various ID cards looked impressive enough to her.

But when they reached the gate, it stood open. The security kiosk was empty. All work had ceased in the rain. Sloan and Saint-Amand exchanged glances. Her eyebrows asked, “Shall we?” His said, “Let’s go.” It was the episode of the helpful PG&E secretary and the gift of the file all over again: No one was guarding the fort.

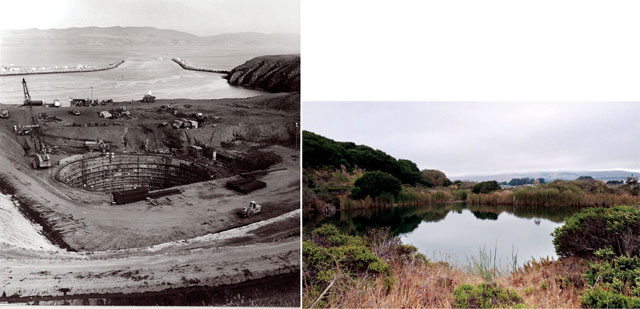

PG&E had been granted a permit for site preparation but not for construction. They dug a pit for the reactor 100 feet deep and rimmed the interior with wooden forms for the concrete—preparation—but they had yet to pour the concrete, as that would have been construction. Campbell Cove was steep-sided, so the company had bermed the reactor hole. The homemaker and the geophysicist set out along that northern berm. “We had walked halfway when Pierre stopped,” Sloan says. “He pulled out his pocketknife. He said, ‘Doris, come and look at this.’ He plunged his pocketknife into a two-meter-wide zone of what’s called a ‘fault gouge.’ That’s ground-up rocks formed when faults move. The movements mush up the rocks. Pierre said this looked like an active fault, a small strand of the San Andreas. You turned around and it went straight smack through the center of the pit.”

This, some argue, was the decisive moment. Saint-Amand’s pocketknife stabbing into fault gouge, according to this theory, was the dagger through the heart of the project.

Afterward Saint-Amand made a formal request, as a government scientist, for aerial photographs of the site. If he proved brilliant at identifying small, distant features of fault ruptures in those aerial photos, then perhaps it was because he had ground-truthed them in advance. He returned to the site officially several times with colleagues for further inspection, and wrote a report, “Geologic and Seismologic Study of Bodega Head.” The AEC staff, given Saint-Amand’s eminence, was compelled to call in the United States Geological Survey. USGS investigators verified his findings, as did other geologists who followed. Meanwhile, the lobbying campaign against the plant gained steam. Governor Pat Brown and Senator Thomas Kuchel came out against the plant. Representative Phillip Burton and Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall stepped in. PG&E saw the writing on the wall, surrendered, and withdrew its application.

“The Hole in the Head Gang,” the press dubbed the motley crew at ncapbhh for the empty reactor pit that is their monument. The gang had won.

Today Bodega Bay is protected as part of the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. The beaches and dunes along the south side of Bodega Head are now Sonoma Coast State Beach. The inshore waters off the promontory are Bodega Head State Marine Reserve and Bodega Head State Marine Conservation Area. At Horseshoe Cove, which 50 years ago Joel Hedgpeth called the “crown jewel” of Bodega and “an ideal marine laboratory site,” there now stands, indeed, the Bodega Marine Laboratory. The lab is run by the University of California at Davis as a part of UC’s Bodega Marine Reserve.

For Doris Sloan, her trespass with Pierre Saint-Amand at the reactor site was pivotal, “an absolutely incredible day, not only for the fight for Bodega, but it changed my life, too.” Watching Saint-Armand sink his pocketknife into the fault gouge was one of the inspirations for her eventual return to school to study geology. In 1975, she received her master’s in geology from UC Berkeley and became a lecturer in environmental sciences there. She often brought her classes out to Bodega Head, and she takes groups there still. At the reactor pit she can no longer point out the fault gouge that Saint-Amand probed, for the berm and its surrounding terrain have become completely overgrown. But the gross features of the San Andreas fault zone are still manifest to the east. The pit makes a podium from which Dr. Sloan can tell the story in situ, a lesson in political geology taught at its very epicenter.

he Hole in the Head has filled with rainwater and is now most often called “the Duck Pond.” PG&E pulled out with little remediation of the site, except to bulldoze surface rebar and rubble into the pit. The ruins of the stillborn reactor lie quite deep. No trace shows at the surface. Migratory waterfowl see the pond as just another of the thousands of bright, reflective way stations along the Pacific Flyway. Widgeon, teal, buffleheads, scaup, ruddy ducks, and other migrants drop down for pit stops. They dive or dabble for a while. Then the Arctic calls them again, or Argentina speaks from the other direction. They make their web-footed runs across the surface, each bird trailing a line of white splashes on the dark water. They lift off and resume their journey north or south.