On the afternoon of August 20, we voluntarily evacuated our home in San Jose. For three nights, I watched the SCU Lightning Complex to our east and the CZU Lightning Complex to our west grow bigger, first on Twitter and later from my kitchen window. The sky looked eerie, waiting to collapse on us. We tried to lighten things up for our seven-year-old daughter. “This is an eerie-ly Halloween!” There was, of course, nothing funny about that week. California was on fire.

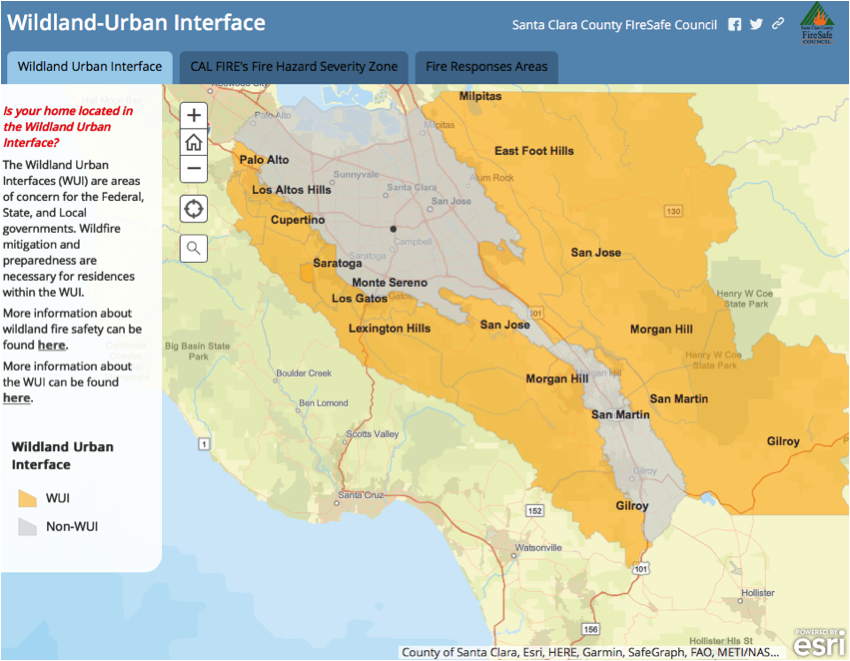

We live in downtown San Jose, so we have never been particularly concerned with preparing for wildfires. Earthquakes, absolutely. Flooding, perhaps. Wildfires, not really. See the little black dot in the center of the map? That’s my home. We’re surrounded by the “WUI” – the “Wildland-Urban Interface” but we’re not in it. Perhaps it is time to rethink the “WUI”.

Although there are different ways of classifying the WUI, designations can be based on a consideration of three factors: housing density; types of vegetation; and buffer distance between housing and dense vegetation. WUI zoning is supposed to help land use planners, emergency personnel and homeowners reduce the risk of potential wildfire impacts. Communities living in the WUI intermix and the interface across California often work collaboratively through Fire Safe Councils and Firewise communities to create defensible space and ‘”harden” homes to reduce the severity of wildfire impacts, particularly from wind-driven embers.

Seemingly, we had nothing to worry about because we’re not in the WUI. So, on August 18, as we followed news of the rapidly expanding fires on our Twitter feeds, we thought, ”it simply cannot happen.” There was no way the CZU or SCU fires were going to send embers flying into downtown San Jose. As the day turned to night, the acres grew, fast and wide, to our east and west. The smoke plumes thickened and hovered over us. Over the next hours, we followed anxious debates on Twitter and the neighborhood app Nextdoor, about whether folks living in east and west San Jose should be packing to go. Could the fires reach us?

It seemed unrealistic, so we mapped it. The fire perimeter for the SCU complex was about 14 miles to our east. The perimeter for the CZU complex was over 12 miles to the west. That’s when we started to consider, what if? This particular year, nothing seems outside of the realm of dreadful possibilities.

Wildfires have overrun urban areas in California’s recent history. The Tunnel fire in Oakland Hills destroyed 3,500 structures in 1991, the Cedar fire in San Diego destroyed 2,820 structures in 2003, the more recent Tubbs fire in Calistoga destroyed over 5,200 structures in 2017, the deadly Camp Fire destroyed almost 19,000 structures in the town of Paradise in 2018. There are simulations of what the future could hold, such as 100,000 structures destroyed across Southern California, by a truly big one.

We also know that wildfires can create their own weather front when they get to a certain size. Even if we were not going to be scorched by flames coming through downtown San Jose, we would still experience the effects – including smoke in our bedrooms and toxic ash raining all over our ”victory” gardens.

As the fires grew on both sides of us that night, we checked in with friends across the Bay Area – in Saratoga, Los Gatos, Cupertino and Mountain View to our west, Evergreen to our east and Dublin to our North. Most of our friends had not realized the fires were growing, and in some cases, advancing toward them. None of them knew if they were in the ”WUI” or what that meant. We packed all night. As we prepared to leave the next afternoon, my daughter fought back tears. She asked if we would ever come back? I held her close. I knew we would come back this time. But I had no guarantees for what the future holds.

There are things we have all learned this year. About wildfires, ourselves and the future. The question so many of us are grappling with right now is this: how do we learn to live with fire? I do not have all the answers, but I can tell you how my family is beginning to prepare. We have a two-pronged strategy: taking responsibility for our personal preparedness and holding institutions accountable for good risk governance. These are of course, related. California’s diverse population cannot take personal responsibility for wildfire preparedness in the absence of enabling governance frameworks, incentives and safety nets.

California has the most densely packed WUI in the United States. Currently, we have just over 11.2 million people living in about 4.46 million homes across 6.7 million acres. As I mused one early morning on Twitter recently, why do we still rely on WUI zoning? Hasn’t it become meaningless? Even if my home is not in a designated WUI zone, surely, I still need to be doing home hardening, weatherizing, and evacuation planning? Being just outside a WUI zone does not magically make me immune to potential fire impacts. Fires can also ignite in urban neighborhoods from utility poles hanging over all our backyards. With an era of extreme heat upon us, it will be important to retrofit our homes and backyards, plan for fire-wise gardens, regularly trim trees, clear brush and mulch from around structures.

We also know that wildfire smoke travels, regionally, nationally, globally, way beyond the WUI. Smoke can hover and linger for days, weeks, months and years, in our homes and lungs, often with chronic mental and emotional health outcomes. However, current home hardening guidance for WUI communities does not include the need to weatherize homes. Homes in the WUI are required to be ignition-resistant, but not smoke-resistant. All of us, even outside currently designated WUI zones, should be hardening (and weatherizing) our homes, and creating defensible space.

Further, designating a WUI zone does not help us address the range of social, economic and health vulnerabilities we’re facing right now. With its focus on homeowners and structural mitigation, WUI-focused preparedness can render invisible so many other kinds of living arrangements and overlook people’s economic and health needs. How do we assess wildfire risk for people who don’t own homes in the WUI but live and work in or near the WUI and are affected by wildfire impacts each year? Renters, migrant workers, seniors and people with disabilities who live in care facilities, people living in mobile homes, on the streets in encampments, evacuees who remain displaced from previous fires. How do we assess their exposure to potential wildfire impacts – on life, health, livelihood? Currently, we do not.

Looking into the future, California would do well to go beyond the arbitrary designation of WUI communities and begin to hold governance institutions accountable to a more comprehensive ‘Policy, People and Places’ approach. An important part of this approach will be to look beyond structural mitigation in the WUI to also protect and restore ecosystem services, especially for rural resource-dependent communities. There are signs of progress as we move from a colonial understanding of the ”wilderness” to embracing indigenous practices of stewardship. Perhaps, if we can ground policy in our diverse experiences, needs and capacities, we will be able to manifest more caring and just pathways to living with fire in the 21st Century.