This is the first in an occasional series on mentors, mentorship, and natural history teaching in Northern California. Find other entries in the series as they appear here: baynature.org/mentors.

The pathway to Agate Beach, at the west end of Bolinas, is one of those trails where you hear the ocean before you really see it. A few hundred feet down there’s a bend, and then through a notch in the hill you get a sudden view of the deep blue over the rocks, and the bluffs of the marine terrace that stretches north along the coast up to Point Reyes.

Right there at the curve, beneath a gnarled and wind-shifted cypress tree, there’s a bench to sit and gaze at the ocean and at its feet a plaque, affixed to a rock. The text on the plaque reads, “In memory of Dr. Gordon L. Chan, 1930-1996 who, to preserve the tidepool resources of this area, was instrumental in the creation of the Duxbury Marine Reserve.”

It is a lovely memorial, and yet, once you learn a little about the remarkable life and enduring legacy of Gordon Chan, a curious one. This small stone with an ocean view is one of only two physical markers in the Bay Area that honors Chan, who died 25 years ago this spring. The other marker is in a 13-tree redwood grove in a median between parking lots at the College of Marin in Kentfield. That plaque is more personal, and reads, “These redwoods planted in memory of a great scientist, teacher and friend.”

The two plaques, as well as Chan’s academic curriculum vitae, tell one story about him: the story of an accomplished scientist and conservationist who played a significant role in protecting several iconic Marin parks. The oral history people still share today, though, tells something more: the story of an unconventional, larger-than-life mentor and friend who taught a generation of people how to see the world.

“Take advantage of the best tides and don’t let it go by the wayside.”

A few years ago, a scientist at the California Academy of Sciences named Terry Gosliner discovered his one-thousandth nudibranch. Gosliner, the Academy estimated, has discovered roughly one-third of all known nudibranch species, and so for the occasion I went to interview him. I asked how he got into nudibranchs, and he said he’d been introduced to them at Duxbury Reef by his high school biology teacher, Gordon Chan.

When the story came out, a reader named Chris McDowell, who had once taken a class with Chan at the College of Marin, suggested I follow up by writing about Chan. Even after 25 years Gordon Chan’s legacy continues to influence science, conservation, and the lives of people up and down the West Coast, McDowell argued. It’s a legacy that extends far beyond being instrumental in the creation of Duxbury Marine Reserve, and one at the same time insufficiently recognized — including a near-total lack of biographical information on the internet.

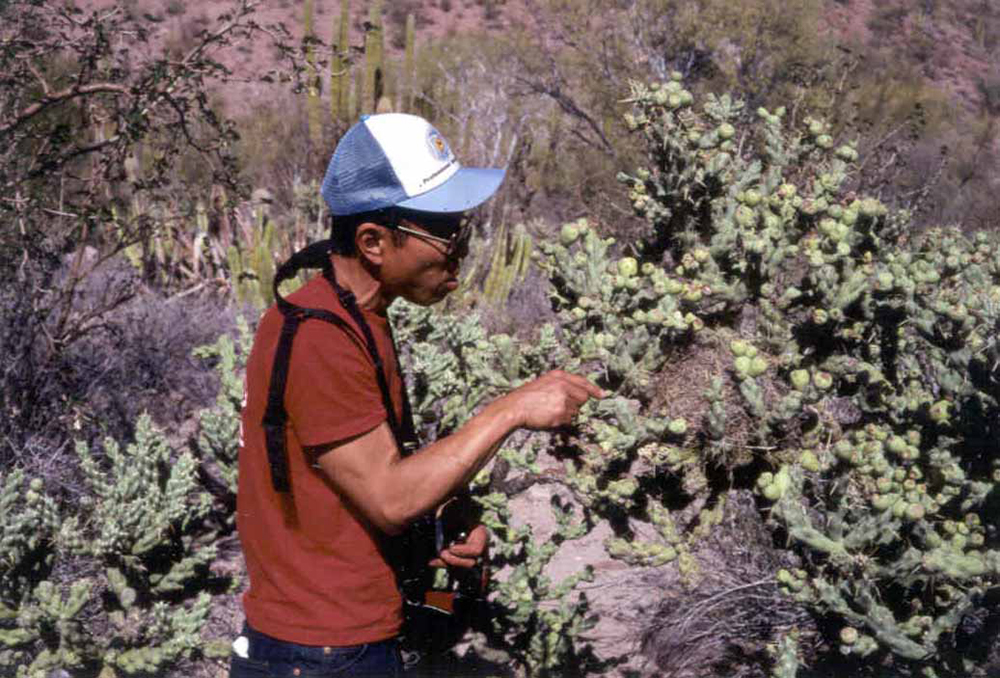

Chan was, formally, the author of more than 24 scientific studies. He received recognitions for his work from the California State Senate and the Marin County Board of Supervisors. He was a research associate at the California Academy of Sciences and part of the state of California’s special committee to study the disposal of radioactive waste off the Farallon Islands. He was a certified scuba instructor and master diver, and took thousands of underwater pictures at dive sites across the Pacific. In the early 1970s, when only four state marine reserves existed in the country, Chan led successful campaigns to create state marine reserves at Duxbury Reef, Limantour Beach, and Point Reyes. His detailed surveys of marine life at Duxbury, conducted between 1958-1971, have given scientists today a valuable baseline against which to measure change.

Gosliner and Gary Williams, also a senior scientist at the Academy of Sciences, met in Chan’s high school biology class in Marin in the 1960s. When they were seniors, Gosliner and Williams skipped a graduation practice to go tidepooling at a spot Chan had introduced them to at Duxbury Reef, and discovered a new species of nudibranch. A few years later they named it after him: Hallaxa chani. Williams said that in heading to the coast instead of school, they were following one of Chan’s maxims: “Take advantage of the best tides and don’t let it go by the wayside. You might not see it again.”

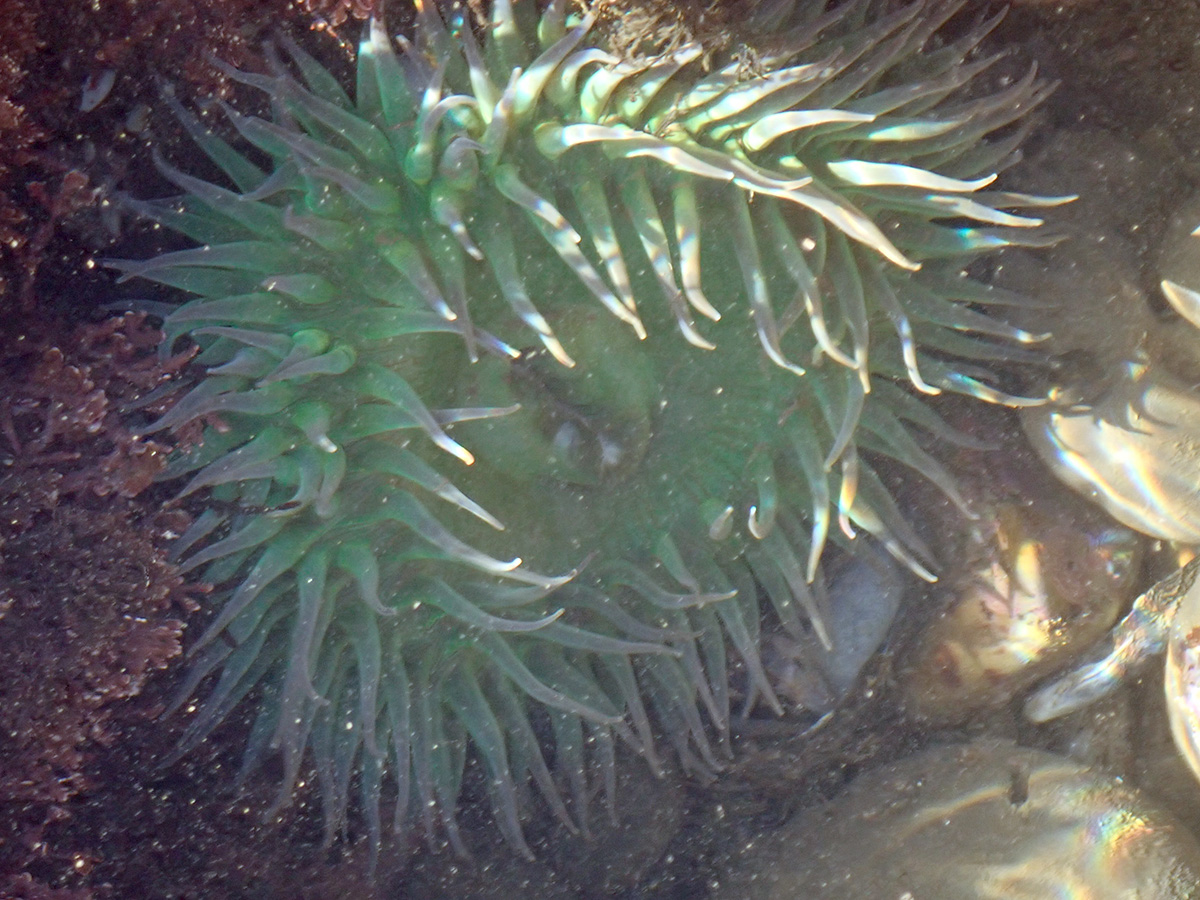

In a recent column in Bay Nature, longtime Marin naturalist Michael Ellis recalled Chan introducing him to a giant green anemone, which Chan had named “Mr. Tony,” at Duxbury Reef in 1984. (Mr. Tony was an affectionate shorthand for the name students had given it, “Anthony Chan.”)

Giant green anemones live long lives, and Chan came to recognize and name a great many of them in his time. Still Mr. Tony was a clear favorite. It was a “beautiful and long-lasting friendship,” Chan once wrote. Tony grew relatively unmolested in one of the remote sections of the reef, and Chan would crush a mussel to feed it every time he visited. Students started to speculate that it had grown to world record size.

After a decade feeding Tony and measuring its growth, Chan recorded that the anemone had put on a good “two inches of muscle.” “This data may be the only vital statistics ever recorded on one sea anemone over a period of time,” Chan concluded in one paper in 1969. “What does all this mean? Well. One could postulate that the more one (anemone) eats, the bigger one gets.”

“Tony,” College of Marin biology professor Joe Mueller told me, “is an obese anemone.”

Even 25 years after his death, many of the things Chan did, and the way he did them, seem hard to believe. His daughters told a story about Chan leading a group of students on a tidepool trip into a private protected area of the Hearst Ranch in San Simeon. William Randolph Hearst Jr. came out to inform them, not kindly, that they were trespassing. Chan not only talked his way out of trouble — the class ended the day swimming in the Hearst’s pool.

“You look at all these things he did, wow he had all the adventures,” said Chan’s daughter Marjorie, a distinguished professor of geology at the University of Utah. “He was the Jacques Cousteau of the Bay Area. He was a leader, he was people’s friend. He had adventures, but he was an activist. Anything he did he tried to see if he could make it better, and engage other people to enjoy the same kinds of things he was revelling in.”

“He was kind of a hellion growing up”

Gordon Chan was born in Seattle, the fourth of five children in the Chan family. The family moved to San Francisco shortly thereafter. His father, a Chinese Baptist minister, died of leukemia when Gordon was five, and the family had a difficult time in the city. To try to keep her boys out of fights, Gordon’s mother moved again to Fairfax, in the middle of Marin. It was a tough place for a Chinese single mother who didn’t speak English. The family didn’t have much money. Gordon fought often and well.

“He was kind of a hellion growing up,” said his daughter Gayle, a retired teacher who lives in the East Bay with her mom, Gordon Chan’s widow Maxine.

“An important part of all this is this combination of the Chinese heritage and living in America, and what that actually meant,” Marjorie Chan said. “In Marin County at the time there weren’t other Chinese families. He was different, and he was discriminated against.”

In sixth grade, Chan’s school principal intervened. If you’re going to fight, he told Chan, at least learn how to do it with rules. The principal taught him to box, offering young Gordon a way to channel his restless energy into something disciplined. Chan’s influential career centered on nature, science, and teaching, but he continued to value athletics his entire life. He played football in high school and went to Stanford on a football scholarship. He later coached track and football. His daughters told a story about Chan, as a teacher, arm-wrestling a student over a disciplinary matter. The agreement was that if Gordon won, the student had to behave. Gordon won.

“We have these stereotypical images of someone getting into trouble, getting on a bad path; do we realize the potential that person has?” Gayle Chan said. “Or a person of low income who feels like they’re invisible and don’t matter. My dad was low income. He understood every human was gifted.”

The same principal who introduced him to boxing also introduced Chan to the Boy Scouts, the second major revelation in Chan’s life. Gordon took readily to the outdoor world of Marin County. He embraced the freedom and independence of being in nature. As a teenager he would take solo multi-day walks from Fairfax out to Point Reyes, camping overnight along the way. He combed the tidepools of the Marin coast, and spent days exploring Lagunitas Creek through what is now Samuel P. Taylor State Park. On scout trips he liked to walk ahead to help set up camp before the group arrived.

“Somewhere in there despite all those hard knocks he experienced, there was a passion for the outdoors, for nature, for the harmony of how we should be fitting in with nature,” Marjorie Chan said. “And the balance of systems. I think in a lot of his research, he was interested in the environment and conservation because he saw the potential to lose so much of what was there.”

“It’s how you take care of things.”

Duxbury Reef falls away from the southwestern edge of the Bolinas Headlands. To get there from most of the Bay Area you have to cross through the San Andreas Rift Zone, leaving the North American continental plate behind and crossing onto the grinding edge of the Pacific Plate. The shale rock that forms the reef rose up in giant blocks from the seafloor millions of years ago, and as the surface eroded away with wind and tide it left behind a vast labyrinth of tidepools.

“The charm and attraction of this whole area may be seen by the aerial photo on the cover of this report,” Chan wrote in a 1969 report called “The Conservation of Marine Animals On Duxbury Reef.” “The gigantic San Andreas Fault along the right side of the photo seems to set apart the Bolinas Peninsula and Pt. Reyes Peninsula as an island in time.”

Chan, who had gravitated to the Marin coast as a teenager, returned with the tools of science after graduating college. He intended to see Duxbury Reef protected, and he set out his scientific transects to prove the need for it.

In his research work Chan divided the reef into three parts. Area A was the first tidepool section a visitor would see, a narrow shelf running along the edge of today’s Agate Beach County Park. Even then, Chan noted, it was a popular and often crowded spot for casual beachgoers. School groups and families visited often, and collection was common. Area B was a shallow shale plain between Agate Beach and the very tip of the Bolinas Headland, matted with surfgrass and popular with recreational fishermen and shellfish harvesters. Area C was the main reef, the tip of the point itself, an arrowhead of rock jutting out into the frothing ocean and separated from the mainland by a dangerous flood channel. Though some harvesters and fishermen ventured out into Area C, its remoteness protected it from most visitors. Mr. Tony the giant green anemone lives its large life in the far-flung reaches of Area C.

All of it, together, forms Duxbury, one of the signature tidepool areas of the California Coast. It is the size, Chan once noted in a paper, of 60 football fields.

“It is not the intent of this report to keep people off the reef,” Chan wrote. “Californians should be able to visit these reefs at all opportunities. The purpose of this report is to recommend that the Duxbury Reef areas be designated a ‘marine reserve’ by the County of Marin.”

Chan established transects at each part of the reef, where student observers would catalogue and measure the number and diversity of the various animals moving through the area. He turned the data into a dissertation project, for which he received his PhD in biology education from UC Berkeley in 1970. Though Chan intended the transects primarily to compare the more and less pressured areas of Duxbury, his careful scientific work almost immediately became much more valuable.

In January 1971 two oil tankers collided beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, spilling nearly a million gallons of marine fuel into the water. The slick, carried by the ebbing tide, flowed out to sea, and then as the tide shifted toward land broke in great black waves over the reef at Duxbury.

Gordon Chan arrived on the scene the same morning, with an incomparable “before” dataset encompassing 13 years of detailed marine observations of the Marin coast. He and his student observers spent the days after the spill walking their transects, collecting data. In his first report, published a year later, Chan didn’t hold back from sharing his conclusions. “The sea has been a dumping ground for the pollutants of the world,” he wrote in the first line.

“I went down to the Seal Rock area at 8:00 A.M. to survey the damage,” Chan wrote in “The Effects of the San Francisco Oil Spill on Marine Organisms.” “The exposed rocks at the seal statue were covered with oil. In the former transect area the oil was so thick in spots that no barnacles could be observed under the cover of the oil, but their coated shells could be felt under the pressure of my fingers.”

The mess at Duxbury was so great, Chan later wrote, that he couldn’t begin transect studies for months because he couldn’t pick out individual organisms. But he knew what should have been there from his previous work. And when Chan and his students were finally able to survey the reef in April, it was clear that a lot of animals had died. Tens of thousands of dead barnacles, thousands of dead snails, and hundreds of dead limpets remained glued to the rocks by heavy oil. Crabs that once would have scuttled everywhere were nearly absent. Chan had observed a small population of periwinkle snails for years and that April couldn’t find one.

Between Duxbury, and transects in Sausalito and Seal Rocks, Chan estimated that the oil spill had killed more than 5 million marine organisms.

The spill galvanized conservationists and state policymakers. With Chan’s earlier research demonstrating its importance, Duxbury was declared a State Marine Reserve a few months later. It has remained protected ever since, and in 2009 was incorporated into California’s statewide network of marine protected areas.

One of Chan’s core beliefs was that science had a purpose. People needed information so they could protect the natural world. Gosliner suggested that Chan, a devout Christian, saw conservation as a deep part of his religious morality. In 1948, in his high school commencement address, Chan quoted the character Portia in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice: “How far that little candle throws its beams! So shines a good deed in a naughty world.”

“If there’s one word that I can associate with Gordon it’s that sense of stewardship,” Gosliner said. “That it’s not just about the observations you make. It’s how you take care of things.”

“Some people would find it tedious. I find it fascinating.”

In 2021, a new wave of change threatens Duxbury Reef. Fifty years after Chan published his first Duxbury transect studies the oceans are warming and acidifying. Sea stars have suffered massive die-offs from Alaska to Baja. Offshore kelp forests have nearly disappeared in Northern California. Despite its protections from fishing, tidepool visitors have surged into Duxbury, especially in the COVID-19 pandemic. But as Chan saw after the oil spill, it’s hard to quantify those changes without a clear picture of the “before”.

Starting this spring, College of Marin biology professor Joe Mueller and — as his mentor Chan would have done — a group of current students have dusted off Chan’s old transects and set out to revisit them. It took some work just to find the exact transects at first. Many of the metal bolts had disappeared beneath 50 years worth of algae and colonial marine animals, making a metal detector a key part of the hunt. But the team has now dropped GPS coordinates at each transect and taken detailed photographs. They hope the survey can continue to be repeated every 10 or 20 years as a long-term study of change.

Laura Miller, a College of Marin student who is working as one of two field technicians for the study, said on her first day on the resurvey project, she also went out and dusted off the Gordon Chan plaque. A 20-year resident of Bolinas who went back to school to get a biology degree at the only community college in the state with its own marine lab, Miller called it a “dream come true” to be one of the technicians picked to help honor Chan’s legacy.

“We’re looking at the exact same species he did,” Miller said. “You spend three hours in one square meter. Some people would find it tedious. I find it fascinating. When you get down there and see the amount of life in that square meter, it is fascinating.”

They’re following Chan’s methodology exactly, she said. She thinks the comparisons will be “shocking.”

“The coasts are the most impacted I’ve ever seen them, ever,” she said. “It’s like Fourth of July out there, every day.”

Mueller, also a long-term Bolinas resident who’s been observing the reef at Duxbury since the 1980s, said that passive signs asking visitors to respect the tidepool life are no longer enough. The ease of access to the reef, and the ease of finding information about it, have resulted in huge crowds overrunning the tidepools. Most of the damage might be unwitting, he said, but it’s nonetheless significant.

Mueller said he, too, expects to find enormous differences between what Chan found 50 years ago and what lives on the reef today, especially in the most-visited areas.

“There’s throngs of people out there with their phones, and it’s just wiped out,” Mueller said. “But there’s Area C, which Gordon designated as a control. That place is just flourishing. There’s still nudibranchs, the diversity is still there, where people don’t have access.”

Mueller and Miller both approach the project, as Chan might have, in the spirit of stewardship. They want their science to help protect Duxbury, again. Miller said that she hopes to see the state fund a docent program for the tidepools, so there’s always someone on hand to make sure people know how to treat tidepool life respectfully.

“It’s long term data and it’s going to be very illuminating,” Miller said. “It could be horrifying, but it could effect change. And protections.”

The resurvey is funded in part by Maxine Chan, Gordon’s widow. Chan was able to spend his life in science because Maxine was there to organize his notes, and type his reports, and raise his three daughters. An exceptional musician with a talent for math, Maxine had no real interest or experience in the outdoors when she met Gordon at a Christian conference at Asilomar. She did notice, however, that Gordon had a nice voice and played the ukelele well. Over a Zoom call she said she was proud to support his scientific work, and recalled that she always felt Gordon protected her.

“I knew if he planned something and if Plan A didn’t turn out, he would take responsibility and have Plan B,” she said. “He took care of things. Really took care of things.”

“Maybe opposites attract,” Marjorie Chan added. “But he taught her to enjoy a lot of these things together as a unit. They were paired partners. He couldn’t have really done a lot of things without her.”

Chan acknowledged as much in the opening of his first study on the effects of the oil spill: “My foremost indebtedness is to my wife Maxine who labored hundreds of donated hours compiling the statistical data and typing this report.”

“An honor and a privilege to serve”

Chan started teaching in 1957, after graduating from Stanford and serving two years in the Army. The profession called him, his daughters say, because he felt that the sixth-grade principal’s intervention had changed the course of his own life, and he wanted to do the same for others.

He worked in Vallejo and at Sir Francis Drake High School in San Anselmo before settling in at the College of Marin. Chan’s scientific legacy centers on the understanding and conservation of Duxbury. His teaching legacy goes further afield. He introduced Terry Gosliner to nudibranchs and inspired Gosliner’s career. He introduced Gary Williams to taxonomy, inspiring William’s career in coral diversity. Gosliner and Williams both published scientific papers before they left high school.

“Treat someone else you’re working with as an equal,” Williams recalled. “He involved us in the field. Involving students in the field was a big deal at the time.”

As senior scientists at the Academy of Sciences, Gosliner and Williams now mentor graduate students. Gosliner said he thinks of Chan’s influence when he leads his weekly lab meetings, which become conversations not just about science but about how to live a meaningful life. He said, too, that has carried Chan’s lessons into his international work, leading to closer and more respectful interactions with scientists and non-scientific communities alike.

“I just think he gravitated toward people and respected them,” Gosliner said. “And listened to them. I remember having deep philosophical discussions with Gordon. He was deeply religious and I wasn’t, and we talked about whether it was more important to be a moral person than it was to have a core sense of beliefs. I remember arguing about it with him. It wasn’t an unpleasant argument. It was a real discussion. I felt he was listening to my point of view, as much as I was listening to his.”

A short biography written by his daughters Gayle, Marjorie, and Sue, quotes Chan saying it “was an honor and privilege to serve” with students, and, “By exercising our love for each other, we can gain direction in our own individual course.”

Gosliner told me a story about how much Chan enjoyed the success of a classmate who became a professional water skier. “It wasn’t just a set of academic accomplishments or one single trajectory that in his eyes really denoted that you were successful,” Gosliner said. “You were successful if you lived a good life and found happiness and reward in what you were doing.”

Chan trusted high school and community college students, and always saw them as capable of generating real scientific contributions. He co-founded the College of Marin’s Bolinas Marine Lab and created the state’s first program to offer community college students a marine technician degree. When a colleague found the fossil remains of a new genus and species of baleen whale in an eroding mudstone cliff at Bolinas, Chan raised grant money to have his students conduct the excavation. They donated the whale to the Academy of Sciences, where it remains in the collections today.

Chan also led field trips up and down the West Coast for students. They explored Baja California, the Grand Canyon, and the redwoods. They went to Death Valley every spring. The trips usually included both students and family members. “We did not have family vacations,” Marjorie Chan recalled. “We had family field trips.”

Chan set students like Gosliner and Williams on their way to fulfilling scientific careers, but he also had a reputation for turning lives around, for unconventional methods that reached hard-to-reach kids, especially young men.

Joe Mueller, now the department chair for the College of Marin biology program, identified himself as one of those hard-to-reach students. He grew up poor in Fairfax, like Chan. No one in his family had ever been to college. They didn’t know what a scientist was, and they didn’t know what to do with what Mueller said was his innate, intense love of the natural world. “I didn’t have much of a family,” he told me. “A stepfather I didn’t like. I didn’t have a good life at that time. Gordon and a couple other teachers saw that I had that extra dose of biophilia. He took me under his wing.”

Chan included Mueller in his field trips and research projects. Mueller remembers waking up at 5 on summer mornings, getting into his wetsuit to go diving out on the coast to count abalone and other marine invertebrates. Chan found money to pay Mueller for his work, which Mueller called a “life-changer.” And Chan told his students that no matter what level they were, they weren’t just going to look at things, they were going to do science.

Propelled by Chan’s teaching and his own interest, Mueller became the first in his family to go to college. Now, as a professor, he’s continued many of Chan’s traditions at College of Marin. He led a campaign to restore and upgrade the school’s Bolinas marine lab, which closed in 2006 and came near to being sold off. Like Chan, Mueller involves students in real scientific work at the coast, and finds grant money to pay them for it. And like Chan, Mueller leads field trips and field classes up and down the state.

“Students get these epiphanies when they’re on field classes,” Mueller said. “‘Wait a minute, I want to learn this!’ That’s an incredible thing for a teacher to be a part of. That’s something Gordon instilled in me: how is it you present the material in a way students want to learn?”

Whether they became water skiers or professional coral taxonomists, Chan taught a generation of people to want to learn about nature. Gayle Chan recalled a conversation with her father in 1994, after he had been diagnosed with ALS. “One of the things he told me was that he almost felt at times that his students knew him better than his family,” she said. “I just interpreted that to mean he considered that perhaps his best self. Being out there in the environment, allowing that to come alive for students who would therefore go out and make a difference.”

“It then becomes very important.”

Chan’s old high school, Sir Francis Drake, is renaming itself this year, and Williams and Gosliner tried to propose it be named after Chan. Their proposal didn’t make the final cut. People do at least continue to find the nudibranch they named after him, Hallaxa chani, around the Bay Area. The West Marin Environmental Action Committee funds a scholarship named after Chan, his longtime colleague Alfonzo Molina, and another longtime College of Marin instructor, Russell Ridge. Former Chan student Sarah Melville and her husband John funded a “Prof. Chan Two-Year College Award for the Engaged Teaching of Biology” through the National Association of Biology Teachers. Maxine Chan funds a scholarship for College of Marin students in the life sciences.

Still the only physical public memorials for Gordon Chan are the parking lot redwood grove at the College of Marin, and the small plaque nestled in the grass about halfway down the trail to Agate Beach in Bolinas. There, you can walk the pathway down toward the water, and sit on the bench, with a view of the timeless blue ocean beyond the constantly changing tidepools.

A marine reserve is a place not just where marine life can thrive, but where the public can go to meet it, to learn to love it and want to conserve it. I suppose you might consider a marine reserve as something more than a place, or a set of rules, but a way of teaching. Gordon Chan, the plaque says, was instrumental in the creation of this marine reserve, as he was instrumental in teaching a generation of Bay Area students. Perhaps the plaque doesn’t capture that legacy. But the plaque marks the gateway to 60 acres of protected reef that almost certainly do.

In the introduction to his first major study of the reef, Chan started with a question: “What is so important about Duxbury Reef?”

“Compared to the magnitude of the world’s social problems, Duxbury Reef does not seem to be of much significance,” he wrote. “However, if one were to consider this reef in light of the intrinsic educational values to man, it then becomes very important.”