Terry Gosliner found his first new species of sea slug as a teenager in a tidepool at Duxbury Reef in Marin, and then just never stopped. For the last five decades he has discovered sea slugs and sea slugs and more sea slugs, to the point it was recently announced he has discovered his one-thousandth species — or something nearing one-third of the known species of sea slug on the planet.

More Sea Slug Content

- Want to go tidepooling and look for nudibranchs? Here’s our guide for the amateur.

- Here’s how Lake Merritt nudibranchs responded after the harmful algal bloom of 2022.

- Nudibranchs feature in this edition of the Bay Nature seasonal almanac, illustrated by Jane Kim.

A curator at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, Gosliner has also named around 350 species of sea slug. He has named them after family members, and friends, and colleagues. Gosliner and Academy scientist Rebecca Johnson discovered a Hawaiian nudibranch in the Thorunna genus and named it Thorunna kahuna. Gosliner discovered a very small black-and-white nudibranch and named the five-millimeter-long slug after the largest black-and-white animal he could think of: Philine orca. When naming a new sea slug, he says, “You’ve got to have fun, and humor, and irony. Something scientists could do more of.”

In 1967, then-17-year-old Gosliner found a white tufted slug in a tidepool in Moss Beach. Cut a golf ball in half and perch a tiny Russian fur hat on it; that was what the thing looked like. Gosliner bundled it and took it to the Academy of Sciences to identify. (He remembers being 15 minutes late to his appointment because the Grateful Dead was playing in the bandshell out front, and it was the Summer of Love, and that’s the kind of thing that happened then. “It was an amazing experience,” he says.)

The slug was Doris odhneri, the giant white dorid or white-knight dorid, and it had been discovered and named only a year earlier. It blew young Gosliner’s mind to find that in this heavily urban place there were still things out there in the tidepools that people were discovering. The Academy’s invertebrate curators handed Gosliner a book and told him to keep exploring.

Soon after he found a miniscule, translucent, brain-like slug on a float in the San Francisco marina; it was Corambe steinbergae, and it was the first time the species had ever been recorded in San Francisco Bay. He turned the discovery into his first published paper a year later. And then in 1968, Gosliner and his high school friend Gary Williams — also now an Academy curator — prioritized attendance at the lowest low tide at Duxbury Reef in four decades over the beginning of high school graduation rehearsal. (The vice-principal, Gosliner says, was convinced they’d forged the note from their parents.) Out on a part of the reef uncovered by the exceptionally low tide, they found something they’d never seen before. It looked like a lemon drop. It had prominent, ringed antlers (technically rhinophores). Gosliner and Williams suspected immediately that it was an undescribed species. They brought it home and were proven correct. In a paper published in 1975 they named it Hallaxa chani after their high school science teacher, Gordon Chan, who had first taken them tidepooling.

As a newly minted adult, Gosliner wanted to keep looking for nudibranchs. Most of the rest of the world told him to find a real job. Biology was going cellular and molecular, delving into DNA. Natural history was in decline. What kind of career line was “knows a lot about sea slugs”? “It was a little daunting,” he says. “I was just so passionate about it, there was no question this was what I was going to do. And I had no way of knowing how to do it.”

The journey to making nudibranchs a career took him around the world. (He organizes the “expeditions and field research” section of his curriculum vitae by ocean basin.) He has degrees from UC Berkeley, the University of Hawaii, and the University of New Hampshire. After getting his PhD Gosliner took a marine biology research position at a museum in Cape Town, where he discovered and described dozens of new species of nudibranchs — including the wildly colorful Bonisa nakaza, the first species in a new genus that Gosliner named after his wife Bonnie Isabel. In 1982 the Academy brought him back to the Bay Area as an assistant curator of invertebrates, and he has been there (in ever-advancing roles) ever since.

In 35 years at the Academy Gosliner has watched the world change, and the nudibranchs with it. Or maybe it’s the other way around. “I was interested in nudibranchs because they’re cool looking, but then I found all these other things you can figure out by using nudibranchs as a model,” Gosliner says. “You could study evolution, or how color patterns came about, or conservation, or how the planet is changing. All these other doors opened up as a result of that passion.”

Nudibranchs can serve as effective proxies for ecosystem health. In a paper in 2011, for example, Gosliner and several colleagues forecast that warming oceans would bring Southern California nudibranch species north. When the Hopkins’ rose and Hilton’s aeolid showed up en masse in Northern California four years later, timed to the rise of the “Blob” and then a major El Niño, Gosliner told Bay Nature he found it scientifically exciting and big-picture alarming.

“In 40 years I’d never seen this Phidiana hiltoni nudibranch, which is only known from south of the Golden Gate, and in one year it became the dominant nudibranch at Duxbury Reef,” he says. “The Hopkins’ rose thing was just mind-boggling too. I went out to Pillar Point and saw more Hopkins’ roses in one tidepool than I’d seen in the rest of my life put together. It’s just bizarre. It’s a mixture of excitement and thrill to see all of these things, but then you question, ‘Well, should this be happening?’”

As an Academy researcher, Gosliner has focused much of his attention on tropical nudibranch diversity in the Philippines. While the cold California current and the warm coral reefs are obviously different places, “the kinds of things you observe are the same,” Gosliner says. He compares it to seeing a Broadway production in New York and London: the actors change, the story’s the same.

Gosliner can recall, with melancholy, the days when he’d dip a butterfly net to catch three-foot steelhead swimming up Marin creeks. He’s alarmed by the lack of access kids have to nature. He remembers Gordon Chan’s high school science class at Drake High talking about increasing greenhouse gases, and realizing the increasing seriousness of the problem. He now sees evidence of humanity’s reliance on fossil fuels wherever he works, in increased typhoon strength or bleached reefs in the Philippines, in warming waters in California, in the shifting nudibranch patterns that Gosliner has always mapped to the world.

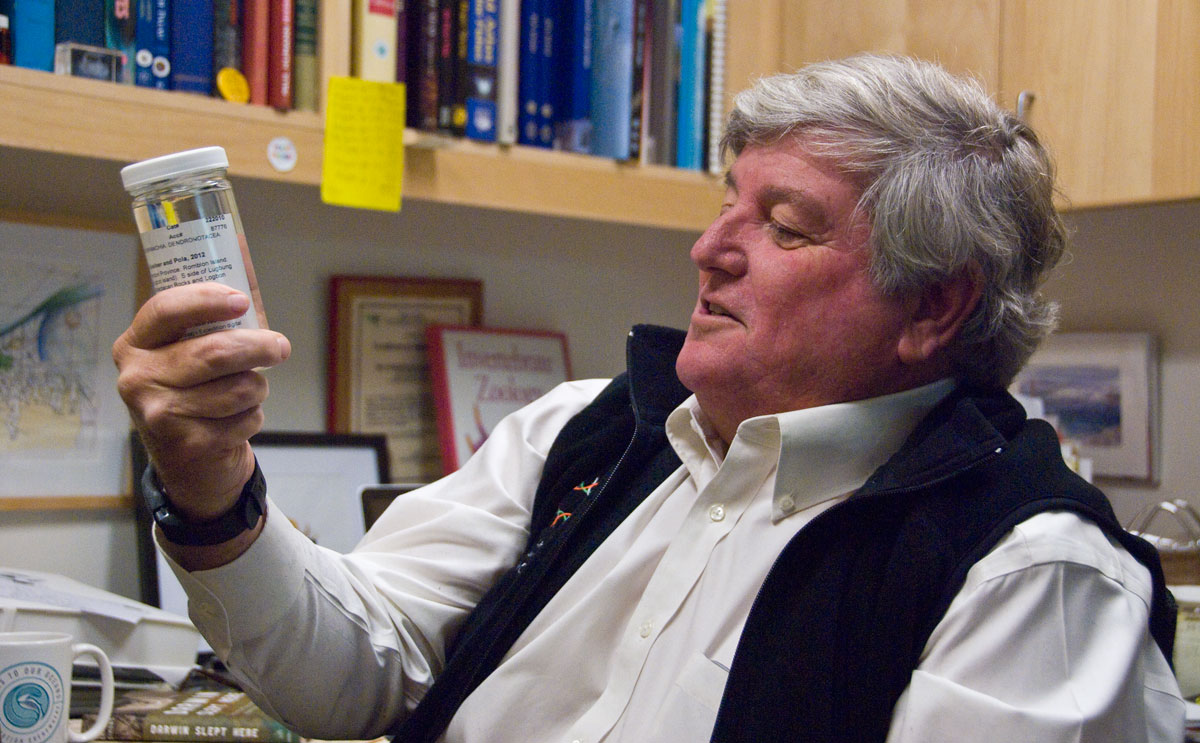

But, he says, he also sees hope. When he was a kid, the San Francisco Bay shoreline would stink from raw sewage. It’s been at least partially cleaned up. Whales nearly disappeared from California, then we stopped hunting them and created national marine sanctuaries and they came back. On one of Gosliner’s first dives in the Philippines, decades ago, the concussive blast of fishermen dynamiting reefs for fish made him feel as though he’d blown out his ear drums. Now the practice has stopped and the coral in many places has recovered. He keeps going back, and he keeps finding new species. He’s found so many he doesn’t even know which one was the actual thousandth discovery, just that a year ago he was closing in on that number, and he went back to the Philippines over the winter, and when he returned to San Francisco the glass jars on his desk were full, as always, with new creatures to be named and described and admired.

“You can heal the environment if you give it half a chance,” Gosliner says. “We know what the solutions are. We need to pursue them as quickly as we can.”