The Bay Area is often associated with two things – the beauty of its natural landscape, and the skyrocketing costs of living in it. Of late those have been seen as being in tension. Should the ridge separating Pittsburg from Concord be developed for 1,650 new houses, or preserve the open space and “watch people move to Texas,” as the San Francisco Chronicle headline put it. Should UC Berkeley be allowed to enroll more students, or does the potential environmental impact of those students on current residents of the city of Berkeley outweigh the benefits? Should the A’s build a stadium and housing at Howard Terminal, or should development on the Oakland waterfront be blocked for bringing environmental harm to a community that’s long been consigned to high air and water pollution?

In each case, lawsuits have turned to the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, sharpening the apparent conflict between new housing and California’s legacy of environmental protection. But while widely read national stories have focused on how CEQA allows neighborhood groups to block region-benefitting developments, a CEQA case over wetlands and housing in Newark illustrates some of the criticisms of the law among conservationists, who argue that it is too inflexible for the environmental threats of a dynamic world.

“I don’t think that anybody really thinks that CEQA works exactly how it’s supposed to,” says Eric Buescher, an attorney with San Francisco Baykeeper, a nonprofit organization dedicated to defending the health of the Bay. “Developers say it is way too restrictive. Cities say it’s expensive and impossible to comply with. Environmental groups say you can’t even get a project that is going to be built for sea level rise reviewed in time for sea level rise.”

Enacted in 1970 on the heels of the National Environmental Policy Act, CEQA requires state and local agencies to “look before they leap” – to assess and reduce any significant environmental impacts from new projects, while keeping the public abreast of how and why these decisions are made. The statute requires a phased process of approval for any project.

After a project is initiated, it goes through a preliminary review to see if CEQA applies to it. If it requires approvals under CEQA, a study documents the areas where it may cause environmental impacts, and whether it complies with other environmental laws and plans. If the impacts are deemed significant the law then requires an environmental impact report (EIR), which assesses the effects the development would have on the area – its population, traffic, schools, fire risks, endangered species, archaeological artifacts and aesthetics. The process also involves creating potential alternatives, and organizing public hearings where residents can provide comments to ensure thoroughness and accuracy.

As a planning tool, CEQA has myriad uses, but its overarching nature also means that it can be used by just about everyone – which is how its implementation has so often come to pit environmentalists against developers and residents against local planners in a region battling a homelessness crisis as well as a changing climate.

“If you give everybody a potential veto, sometimes strange or bad outcomes are going to occur,” Buescher says, “where you get a judge that misses something or interprets the law in a certain way, or you get a plaintiff who is asserting a particular agenda, and that’s not really the intent of CEQA.”

The Berkeley story has dominated the news cycle, but Newark’s Area 4 development has been mired in controversy since the city zoned it for development in the early 90s. Environmentalists have long wanted to add Area 4 to the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge as upland migration space – to preserve room for wetlands to move inland as sea levels rise on the Bay shoreline.

In January 2022, after a protracted battle, the Citizens’ Committee to Complete the Refuge (CCCR) lost a CEQA appeal in California’s 1st District Court against the City of Newark, removing one of the final roadblocks to the construction of 469 single-family, low density homes on elevated peninsulas close to Newark’s shore.

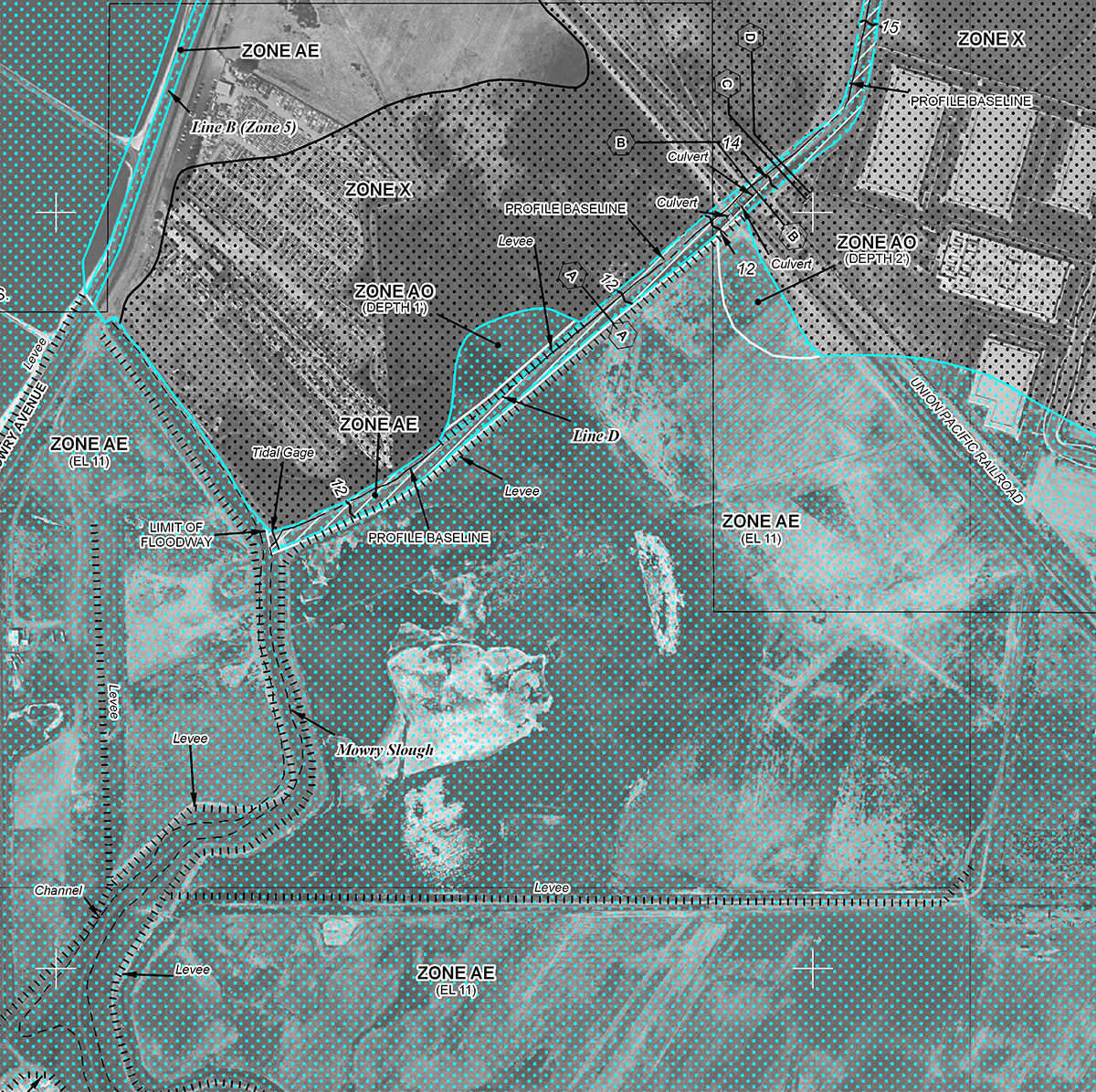

Most of Area 4 is in the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s “AE” flood hazard zone, which means that it is already at risk of flooding, and would be inundated in what hydrologists call a “1-percent storm.” According to the EIR, the city plans to “build levees or floodwalls built on top of or outside the raised and filled residential areas” when flooding becomes more regular in the future.

Opponents of the development argued in court, though, that the EIR didn’t assess the impacts of floodwalls or levees the project will ultimately require. One set of floodwalls or levees won’t cause a big ripple in the waters of the Bay, but if every city does it, it could lead to the entire Bay perimeter being walled or “hardened”, causing cascading regional impacts. In a 2021 article in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, University of Texas Arlington civil engineering professor Michelle Hummel and colleagues found that city-scale floodwalls might prevent local flooding while enhancing far more costly regional flooding. Newark’s decision to build on the shoreline now makes it extremely likely that it will then build those walls to protect residents later – an impact CEQA doesn’t force anyone to consider.

“Developing now in an area we know will be inundated by sea level rise commits us to specific actions in the future,” Buescher wrote in an email. “Building a wall around one place to protect its residents exacerbates the impact of sea level rise on nearby communities at the same time it limits those communities’ options to respond. CEQA, as currently used, does not involve analysis of those future commitments, nor assess the regional impact of those future actions on the environment. As a result, we approve projects without considering the long-term region-wide impacts they will have, and in doing so limit the flexibility available in the future to respond to the impacts of sea level rise on a regional basis.”

The Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge argued in court that Newark should address the environmental impacts the measures would create. The judgement disagreed, stating that “sea level rise was not an impact on the environment caused by the project, so neither the REIR (a recirculated EIR) nor the checklist needed to discuss the effects of sea level rise on the project at all.”

The checklist is how project proponents show CEQA compliance – they go through the list and mark sections with the level of likely impacts and explain why they checked what they did, after which the public comments on the draft. The governing agency then makes a decision – the project is either greenlit or somebody sues. Because CEQA tends to pigeonhole environmental impacts into checklists, the fight is often over how someone checked off these boxes, as opposed to asking whether it makes sense to develop the shoreline in Newark, in a location that is going to be impacted by groundwater flooding and sea level rise. “We don’t ask these bigger picture questions very often in the CEQA context,” Buescher says. “The idea that this is not a two way interaction – I think we’re missing the forest for the trees.”

While it is true that under CEQA projects need only consider their impact on the environment and not vice-versa (sometimes referred to as reverse-CEQA), long-time practitioners say that this is contrary to how it has been implemented for over four decades. “The way that courts have been interpreting CEQA lately, you wouldn’t need to look at that,” says Richard Grassetti, an environmental planner with expertise in CEQA compliance.

Grassetti mentioned two recent court decisions that emphasize the point. In the Ballona Wetlands Land Trust v. City of Los Angeles, several environmental groups sued to try to stop a shoreline development project in Santa Monica, arguing that its EIR had not adequately considered sea level rise. The California Court of Appeal rejected the claim in 2011, and wrote that “while an EIR must identify and analyze the significant environmental effects that may result from a project, it is not required to examine the significant effects of the environment on the project.” In 2015, the California Supreme Court took up an appeal from the trade group California Building Industry Association, which had sued the Bay Area Air Quality Management District to prevent new air quality standards for construction projects. With some limited exceptions, the court wrote, “we hold that CEQA does not require an agency to consider the impact of existing conditions on future project users.”

“If the Building Industry Association decision hadn’t come down, you would be looking at impacts of the environment on a project,” Grassetti says. To fix this, he argues, “the state could pass legislation that would just add a sentence clarifying that CEQA requires looking at both impacts of and on the environment.”

And one of the biggest impacts will be sea level rise. But here too, the Newark judgement seems at odds with CEQA’s goals. Because the range of projections for sea level rise between 50 to 80 years from now are wide, and different ends of those projections could warrant significantly different responses, the court decided that the City was not required to analyze the impacts of adaptive pathways at all.

This decision was based on a 2020 case, Environmental Council of Sacramento v. County of Sacramento, which said that an EIR didn’t need to discuss future developments which were unspecified or uncertain because such an analysis “would be based on speculation about future environmental impact.”

But both Grassetti and Buescher argue that sea level rise isn’t speculative anymore, and that EIRs could use currently available range estimates, just like they do for air quality, or greenhouse gas emissions, and discuss the whole range of projections in their analyses. In fact, a key finding of a 2017 report created by the California Ocean Protection Council Science Advisory Team said that when it comes to making decisions today regarding future sea levels, “waiting for scientific certainty is neither a safe nor prudent option,” and “consideration of high and even extreme sea levels in decisions with implications past 2050 is needed to safeguard the people and resources of coastal California.”

“CEQA was made to avoid, or at least mitigate an environment impact. And one of the biggest ones in the Bay Area is sea level rise,” Grassetti argues. “So we need to structurally change [CEQA] to look into the future, to look after the future.”

But in the meanwhile, less reliance on CEQA and more hyper-local work with city planners to help them visualize their general plans into the future might offer a better path forward. General plans are long-term documents that become the basis of the zoning codes and regulate project development within various areas of a city. Baykeeper is now working with cities to ensure that they plan for toxic sites that exist within the sea level rise zone – sites that are not at the edge of the Bay now, but which will be over the next 50 years. “Cities need to plan how they are going to handle development or not-development in these areas,” Buescher says.

He cited Alameda as an example of a city planning well for the future. It definitely needs to – with six to seven feet of sea level rise expected in 80 years, Alameda will have to improve 25 miles of shoreline at a cost of $10 to $20 million per mile.

In 2020, the city conducted a study on groundwater issues which showed that sea level rise would elevate the water table as well, and cause more flooding and soil contamination in every neighborhood in Alameda. This month, the City Council will adopt a Climate Adaptation and Hazard Mitigation Plan.

“There needs to be a lot more of this in every single community throughout the Bay, even, or especially when it’s really hard to do,” Buescher says. “So that the whole system moves in the right direction despite problems as wide and varied as housing, environmental protection, development, and climate change.”