Today marks the release of Bay of Life: From Wind to Whales, a new book about the Monterey Bay region, from photographer Frans Lanting and writer Christine Eckstrom, both longtime contributors to National Geographic. Lanting has created some of the world’s most iconic images of wildlife and nature, while Eckstrom is also a videographer and producer. Their work together has spanned the globe over thirty years and includes projects such as Eye to Eye (Taschen, 2003) and LIFE: A Journey Through Time—plus more natural history books, exhibitions, and even a multimedia symphony.

They are also, it turns out, longtime Bay Nature subscribers, with a near-complete archive of our print magazine at their home in Santa Cruz! This month, we spoke to the husband-and-wife team about Bay of Life—a big, sweeping book that envelops you in the Monterey Bay ecoregion, from the inland areas out to the ocean.

Learn more and go: Check out the Bay of Life project on Lanting.com. Lanting and Eckstrom are doing a number of public events (all posted in our events calendar). These include a Zoom webinar with Frans Lanting (today at noon; registration required), several open studio events and multimedia presentations in Santa Cruz, and a one-day photo workshop with Lanting on seascapes, in Monterey.

This interview has been condensed and edited. An excerpt from Bay of Life will appear in the winter 2023 issue of Bay Nature magazine.

Tell me a little bit about living in Monterey, and how you were inspired to work in your own backyard.

Lanting: It’s harder to recognize the natural qualities of the Monterey Bay region, because it’s inhabited by people. It is definitely not a pristine ecosystem. But there’s a vitality to the Monterey Bay region, and a uniqueness.

In Bay of Life, we aim to explain why it is so good to be here. We dig deeper than just the natural beauty. We explain the seasonality of it, which is quite unique. It’s driven by a Mediterranean pulse. And we also explain the diversity of habitats, both onshore and offshore. That all adds up to quite an extraordinary story. The Nature Conservancy declared that the Monterey Bay region is the hottest hotspot of biodiversity in all of North America.

Tell me about what the Monterey Bay region is facing, and what it needs.

Eckstrom: Connectivity for wildlife is one—being sure that animals like mountain lions can safely travel between regions.

Protection of habitats, and restoration of habitats, is another big, big item on the list that began in the past fifty years. It’s been very successful in many places, with regeneration of forests and the return of marine life that was extirpated or decimated. But there’s still a lot to do.

Lanting: For the protected areas—we include a map in our book—there’s a need for more stewardship. There’s a lot of public and private investment, but they need more attention, because more and more people come and visit them. There’s now a new concept of overtourism, and that is definitely beginning to impact our protected areas.

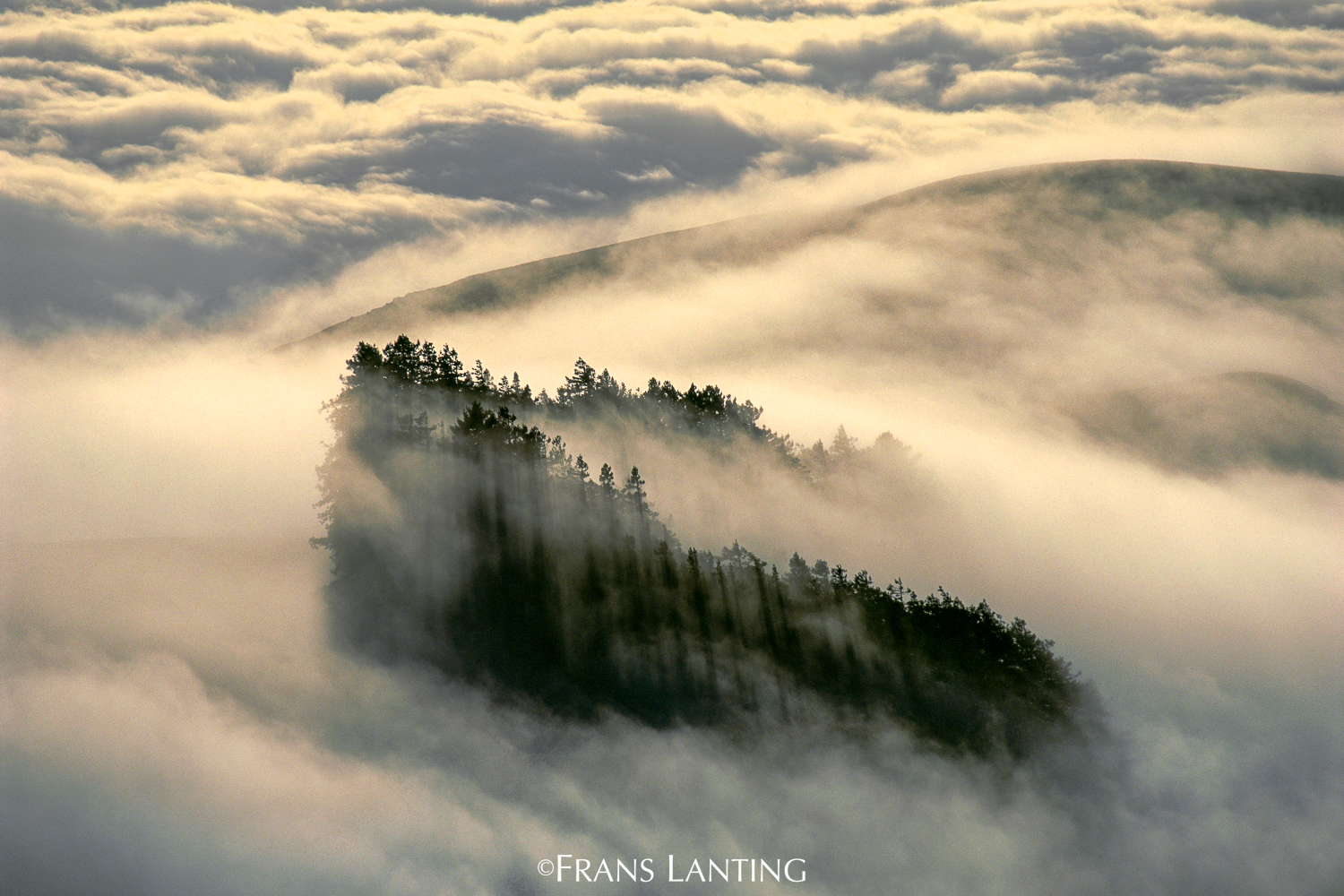

There is a need to prepare for impacts from climate change. And that begins with our water resources, which are finite. We live on a very limited baseline of water that comes from the ocean and comes from the sky—it’s a very fickle reality. Without fog, Monterey Bay will begin to look more like Orange County. How do we live with fire in our midst? With all these protected areas and the buildup of fuel, we now have the reality of fire on an annual basis to cope with.

But we have a record of community engagement, we have a record of public stewardship. That is really worth building on for the next chapter in the history of how people live and work with nature here.

Eckstrom: We have a big disparity between a lot of the people who live along the coast, who in many ways are quite privileged, and the inland communities, the farmworkers—the interior regions that don’t have as much access to the wild nature. We plan to publish a Spanish-language edition of the book in 2024 that we want to get into the schools, and into the hands of people who can help educate the kids and make a difference.

This is more than a book. Julie Packard, executive director of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, in her introduction called it a “portal.” How do you talk about what the project is and what you’re hoping to do with it?

Eckstrom: As an ultimate goal, we want people to view it—land and sea—as a connected ecoregion, and not just the land trust properties or the parks or the marine sanctuary. We think they’re going to be more appreciative and more supportive of efforts to protect it when they see it that way and they see themselves as citizens of a whole ecoregion.

Lanting: We hope to install a sense of place. Santa Cruz is not like Monterey, and it’s not like Salinas, but we share the same natural resource base.

In the last fifty to one hundred years, Monterey Bay has been healed from the the impact of the nineteenth century, when the Santa Cruz Mountains were stripped bare of trees, the bay was stripped of fish and marine mammals. That has been turned around not just because of the resilience of nature but because of active intervention by people. So the story actually has relevance far beyond the limits of Monterey Bay. Because we are looking at damaged ecosystems all over the planet.

How did working on this project change your own relationship with the region?

Lanting: We knew that it was special, but we just went from one discovery to the next. I was out on the Bay just last week with a turtle biologist, looking for leatherback turtles, which swim all the way across the Pacific Ocean from Indonesia to Monterey Bay to eat jellyfish here. That’s extraordinary.

Eckstrom: Last summer, when we were alerted by State Parks that there was a rare nest discovered of a marbled murrelet—a super-rare seabird—we went there to hopefully watch it fledge from the nest, which happens almost at dark. Of the people who gathered there, there was one ornithologist who has been looking for nests for ten years. Ten years he’s been walking around those forests searching and searching for marbled murrelet nests! He happened to see a murrelet fly by with a fish in its mouth, and he followed it and knew it was going to feed a chick.

And all these ornithologists and other researchers, who have been studying the murrelets for like thirty, forty years in some cases, were all gathered there with their spotting scopes looking up. We saw it fledge. It was just so amazing to be among all those passionate people who care so much for every individual bird or animal.

Eckstrom: And something else about this project: We wanted to create it ourselves and not do it under the auspices of a National Geographic or some other entity. Being able to give it to our community is really gratifying.

On a political level, our area has been redistricting since the last election, and we don’t have unified representation for the Monterey Bay region. We’re hoping that the book can also serve to educate new legislators and new representatives who may not understand what it is they have in their new district.

Lanting: Monterey Bay has become the big backyard for millions of people from the San Francisco Bay area. We feel it is important to tell the story of how unique Monterey Bay is for people who don’t have prior knowledge of it, and also to define it separately from the San Francisco Bay.

Bay of Life is a coffee-table book, and the writing is often quite spare, but a lot of background research went into it. Tell me about the process of boiling down an entire ecoregion.

Eckstrom: A lot of young writers [at National Geographic], as I was there many years ago, start their careers writing what they call the legends, the picture captions. You’re trained to encapsulate all the main points of the story in the picture captions and use each image as a springboard, to tell a story that’s embedded in the story. And also to tell it very succinctly.

Frans understands that very well, too. He’ll winnow it down, and I’ll winnow it down, but we work very hard to get a lot of information out in a small piece. There are more drafts than you can possibly imagine for every text that’s in that book.

Lanting: We also included images by other photographers, including historical photographers and images from researchers, so that there’s more than one point of view. We really wanted to represent different perspectives from Native Americans, people who are here as newcomers, science perspectives, and so on.

Frans, tell me a little about your photographic process—including how you think about what you’re looking for, as you enter a scene.

Lanting: Some of the images are very well researched and planned. But ultimately, there is an element of serendipity. You can’t plan for light—light happens when it happens. So I have to be prepared to act on Plan A and then switch to Plan B when the circumstances change.

There is an image of redwoods in the book that was inspired by a famous landscape painter Albert Bierstadt, who created fantastic paintings in the middle of the 19th century with a very unique kind of light. I decided to replicate that by going into a redwood grove with a team of eight assistants to create a similar kind of textured lighting. That was a big production.

Then there are other images that just happened. Chris and I live in the country; our property borders on a state park and is next to a national monument, and we have a lot of wildlife there. We’ve nurtured our land as a sanctuary of sorts. On a micro-scale, we now have red-legged frogs in a little pond right next to the house. And Chris has been nurturing monarch butterflies.

Were there scenes you encountered that stuck with you?

Eckstrom: I think of the cover of the book, with the lunging humpback whales and anchovies spilling out of their mouths and then seeing birds flying overhead. They burst up out of the scene. You just don’t know where it’s going to happen! You look quickly for a little boiling surface, and then up they come. And there were sea lions also arching all through the whales. It was just such a feast, and such a gathering of wildlife.

Lanting: We ran a small boat that we had chartered, so we could move ourselves around the whales without affecting whatever they’re doing. Before we started Bay of Life, I might have chosen to be at the other side, with the whales against a cleaner ocean and sky background. But we chose to be where we were because it showed the proximity of the whales to the shore. And if you look carefully, you can see human infrastructure in the background. I think that is what Bay of Life is all about.