Back when what is now Monterey Bay lay hundreds of feet below the ocean, there was a clam.

The clam lived. It grew to about 4 centimeters across. It died. And that was that—until eight or 10 million years later, when, last month, a road construction crew dug up its likeness preserved deep in the Monterey mudstone and called Wayne Thompson.

With trusty dental picks and tiny brushes, Thompson carefully unearthed the clam print, which was not in good enough condition to determine the species. Thompson has been studying fossils around Monterey Bay for over fifty years, and is CEO of Pacific Paleontology, which helps cities and construction companies avoid destroying fossils lurking belowground.

A week later, at the same site, Thompson found a fossil of a pea crab, Pinnixia galliheri, which once lived symbiotically in the shell of its clam host. He wrapped the clam and crab fossils in newspaper, and sent them off to the Pacific Grove Natural History Museum for further study. Thompson is still surprised by what he can find at digs.

“It’s kind of like Christmas,” he says. “You don’t really know what you’re gonna get!”

For researchers like Thompson who know how to read them, clam fossils have ancient stories to tell. Peter Roopnarine, curator of invertebrate zoology and geology at the California Academy of Sciences, says it’s like “time traveling, in a way.” Clams offer a uniquely detailed fossil record. As they build their shells, layer by layer, clams preserve clues to the climate they lived in—from chemical signals that reveal past temperature patterns to ecological data.

“Clams have this really rich biology and this rich ecology that gets preserved in the shell,” Roopnarine says. “Just looking at the clams will tell you the climate history of the Bay Area.”

Roopnarine compares fossilized communities to living ecosystems to learn how ancient creatures responded and adapted to the climate changes of their day—and beyond that, predict how future climate change will affect similar ecosystems in the future.

These are baby fossils

Far older fossils than the Carmel clam can be found elsewhere in California—there are 80 to 100 million year old specimens in the Redding and Shasta area, and 500 to 600 million year old fossils near Death Valley. Most fossils in the coastal Bay Area are just whippersnappers in comparison—only 15 to 16 million years old.

“These are young fossils, baby fossils,” says Roopnarine. “Paleontologists would say they’re not even really fossils, because they just died yesterday.”

Because Bay Area fossils are so “young,” many of them have close relatives living right off the coast. Fossilized clams in Tomales Bay, for example, are the same species as living clams now found in the Gulf of California, indicating that Tomales Bay was much warmer when those fossils were alive. When Ice Age glaciers were retreating 500,000 years ago, warm water species migrated north—a phenomenon we’re also seeing today as temperatures rise. Even without humans, Earth’s climate would still be getting warmer coming out of the last Ice Age—but the rapid rate of today’s climate change means many species do not have enough time to migrate, adapt or evolve in response.

These ancient changes in climate and sea level are written in Monterey Bay cliffs, including Thompson’s favorite fossil spot: the Purisima Formation at Capitola Beach in Santa Cruz County. The beach’s oceanside bluff reveals a “bone bed,” a rich set of fossils covering hundreds of thousands of years and 80 instances of sea level rise and fall.

“We see those cycles of sea level rising and falling preserved in the strata of the rocks,” says Thompson. “Associated with that, we see migrations of warm-water species and cold-water species.”

How to read a shell’s story

Roopnarine uses clamshell chemistry for a more precise peek into the past. As a clam grows, it adds layers of calcium carbonate to its shell, not unlike tree rings. Researchers scrape samples from these layers and analyze the different isotopes of oxygen that are present within the calcium carbonate. Shells containing a larger amount of the lighter oxygen isotope, oxygen 16, suggests the water was warmer when that layer was made. More of the heavier oxygen isotope, oxygen 18, means cooler temperatures. Put it all together, and “we can see climate varying in the past,” Roopnarine says.

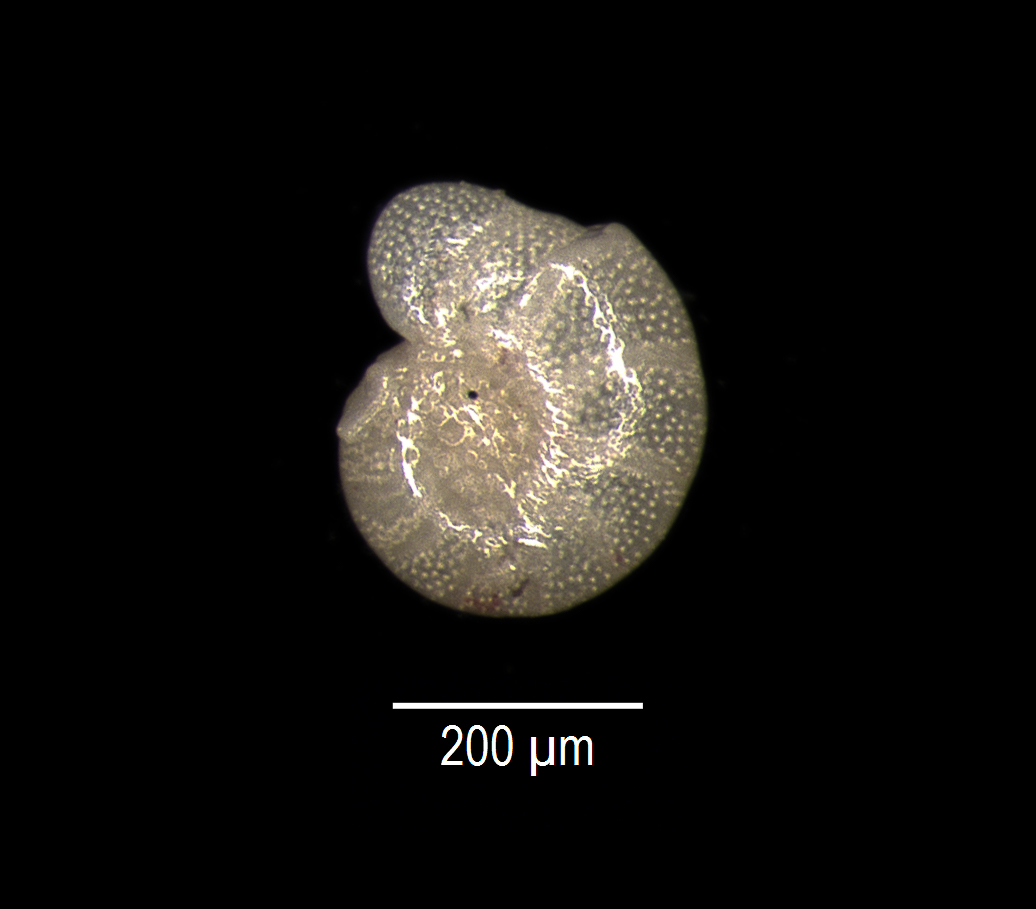

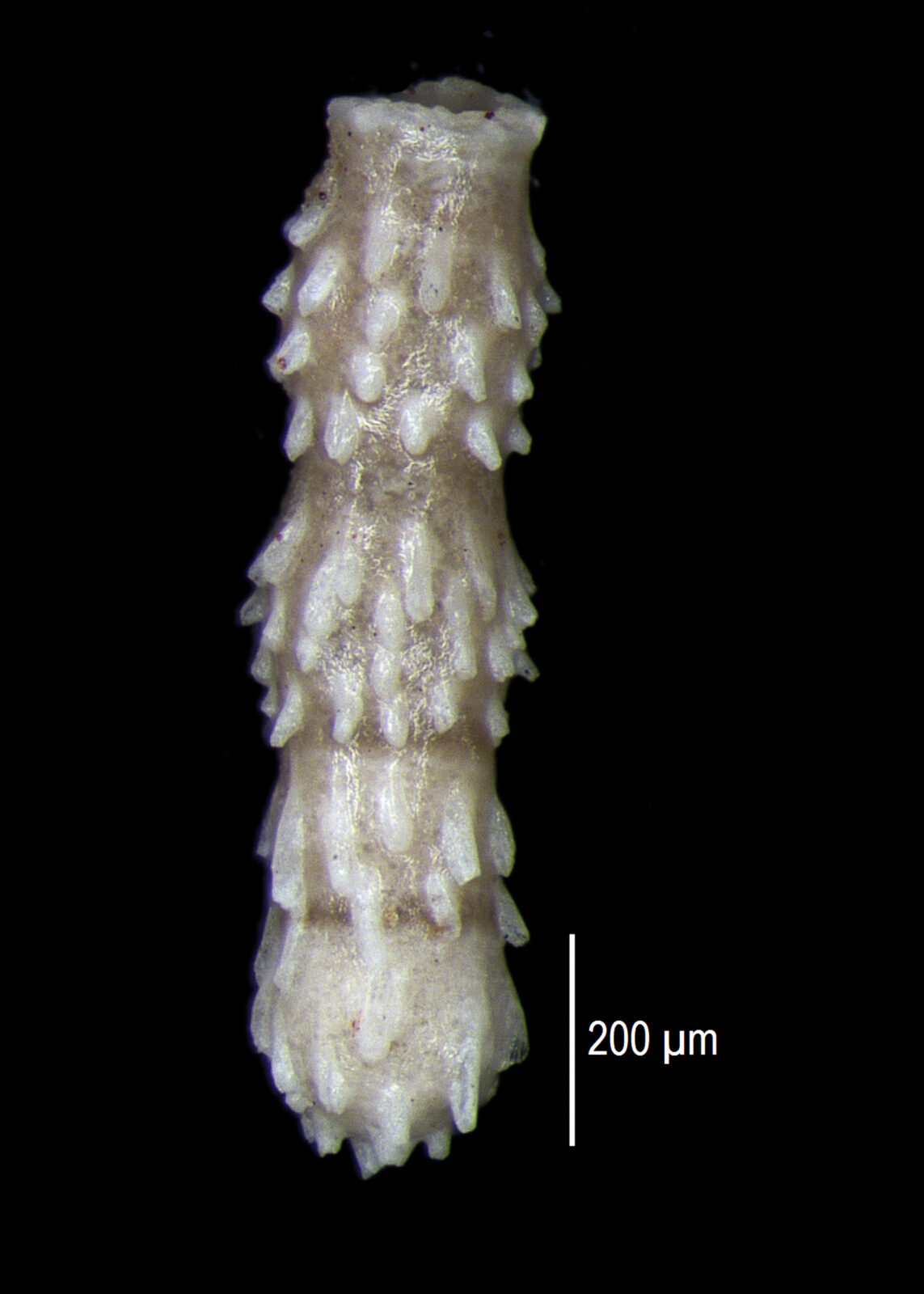

Beyond clams, another paleontological darling for clocking climates of the past are the foraminifera, a class of protists Roopnarine calls “amoebas with a shell.” Foraminifera, called “forams” for short, evolve so quickly that paleontologists use the changes in their uniquely shaped shells to tell time. Under the microscope, grains of sand can reveal themselves as a menagerie of tiny foram shells, from spiny spirals to sand-castle-like blobs and loopy tubes.

Forams are abundant in the ocean. As they die by the billions, their skeletons rain down to the seafloor to become, eventually, a rich deposit of fossils. The shapes of foram fossils found in a rock layer can tell geologists both the relative age of the rock and whether it’s likely to contain oil reserves, among other things. When a variety of foram species are fossilized together, researchers can even use mathematical equations based on species type and abundance to estimate the water temperature that they lived in.

“It’s a really exquisite record,” says Roopnarine. “You can see how the climate has varied over the last 66 million years, globally.”

While clams don’t have quite the continuous and globally abundant fossil record of the forams, their fossils are especially dense with information. Roopnarine has reconstructed droughts over the past thousand years by tracking tiny fluctuations in clamshell chemistry at the mouth of the Colorado River.

Paleontologists take the long view

For Roopnarine, clams offer a mind-blowing glimpse of the dramatic changes Earth has undergone over millions of years.

“There’s millions of species on the planet, and you just might overlook clams,” he says. “But they tell a really rich story. It’s absolutely crazy, the story that life has been telling on our planet.”

For Thompson, studying Monterey Bay fossils is a way to understand time and his home more deeply.

“Getting a perspective of time that’s on a bigger scale than our own lifetimes is really enriching,” says Thompson. “It takes you in and allows you to become part of that history.”

One day, Thompson hopes to become a fossil himself.