How to be HAB-smart this summer

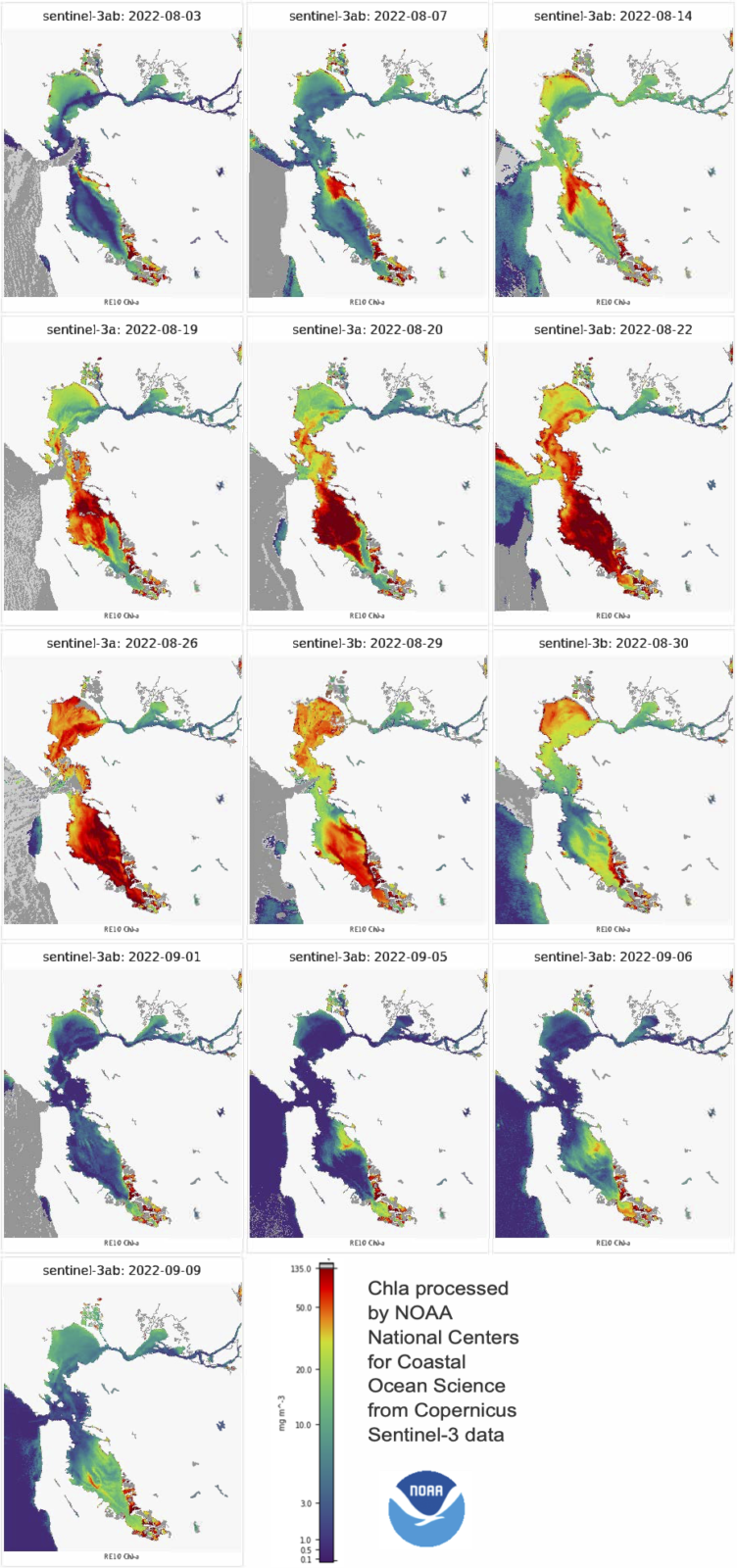

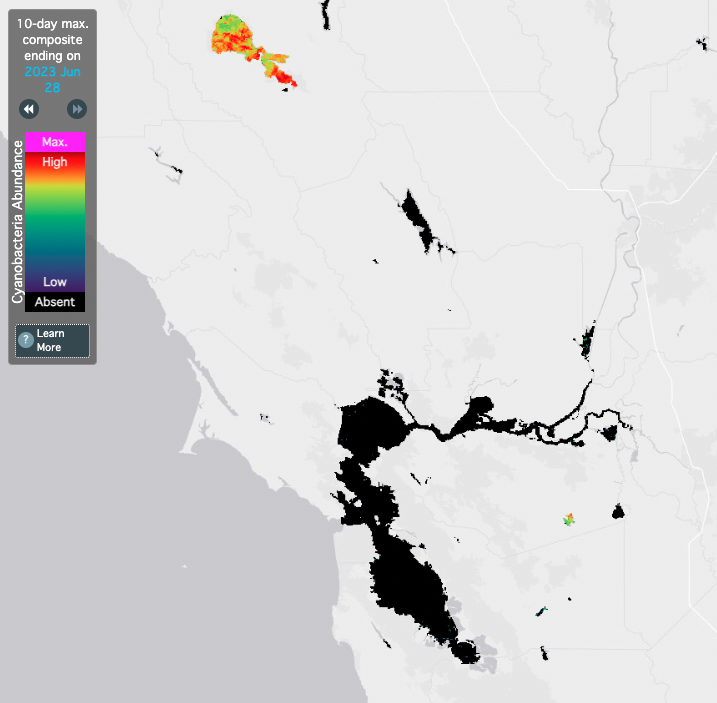

HABs, or harmful algal blooms, are hard to predict. No one knows whether another one will strike the Bay again this summer, but researchers are monitoring water quality with surveys and discoloration with satellite data (which detects the chlorophyll in the algae).

Be safe: Want to check for reported blooms before you go to a local beach or swimming hole? Check the California Water Monitoring Council HAB report map.

Help out: If you see discolored water, an algal mat, or other evidence of a potential harmful bloom, report it to the California Water Board here or via San Francisco Baykeeper’s pollution hotline.

Starting in July 2022, a dark, reddish-brown tinge crept across San Francisco Bay, leaving dead fish in its wake. Carcasses piled up, first on the shores of Alameda and Lake Merritt, then South Bay, then all the way to Point Pinole. In a matter of weeks, more than 800 sturgeon and countless other fish perished from a lack of oxygen and, possibly, algal toxins.

Last summer’s “algaepocalypse” was the Bay’s worst harmful algae bloom ever recorded. Since then, officials from wildlife, water, and health agencies have been scrambling to piece together what happened—and how future algae blooms might be prevented. Ten months later, they are just starting to get answers.

One human-caused driver has been clear from the start—the sheer amount of nutrients flowing into the Bay that fed the algae, via wastewater, agricultural runoff, fertilizer, and urban runoff. The key elements in this mix are excess nitrogen and phosphorus, which feed algal blooms.

This nutrient pollution problem will be very hard to fix.

“While we don’t understand what triggered the harmful algal bloom last summer, we do understand that it wouldn’t have been able to grow to the magnitude that it did without nutrients in the bay,” says Lorien Fono, executive director of the Bay Area Clean Waters Agencies, which represents the 37 wastewater treatment plants that collectively discharge more than 121,000 pounds of nitrogen into the San Francisco Bay every day.

Now, researchers and water agencies are searching for ways to lower the risk of another worst-case bloom by reducing the amount of nutrients in the Bay. There are currently no tried and true techniques to prevent or treat harmful algae blooms, and even reducing the nutrients that fuel their growth has proven to be a political, financial, and technological challenge.

Bloom and bust

Of all the factors that create conditions for runaway algae growth, nutrient pollution is the only big one that humans directly control. Nitrogen in particular is the main nutrient limiting algae’s growth in the Bay, so when there’s a lot of it floating around—and the water is warm, stagnant, and suffused with sunlight—algae can boom. But once the algae have used up all the nutrients, they bust—all dying at once. This is what creates the dreaded low-oxygen “dead zone” that asphyxiates fish and other wildlife. Some algae can also make deadly toxins that poison wildlife, harm pets and contaminate drinking water, depending on which species wins the bloom lottery.

“We can’t control the strength of the tides, can’t really control climate change in our region or the amount of fog over the Bay, we can’t control sun distribution,” says Ian Wren, staff scientist at San Francisco Baykeeper. “Given the fact that we know that the vast majority of the nutrients are derived from municipal wastewater treatment plants, that’s a place to start.”

San Francisco Bay has long been one of the most nutrient-rich bodies of water in the world, and most of the annual load comes from wastewater treatment plants—65 percent. The other big sources are agricultural and urban runoff containing nitrogen fertilizers and other chemicals. But that flushing is mostly restricted to rainy winter months, while algae blooms are more likely to happen during the dry season, when it’s hotter and less water is mixing into the Bay. “The summertime sources are predominantly wastewater,” says Bergamaschi.

For decades, we were lucky. Plentiful sun-blocking fog and sediment suspended in the water, the mixing of the tides, and abundant filter-feeding clams all worked together to keep the Bay’s algae in check, despite all the nitrogen flowing into it. But that delicate balance seems to be shifting. The water is becoming less silty, allowing sunlight to reach greater depths. The air is less foggy, which leads to warmer water. Bloom-boosting summer heat waves are becoming more common.

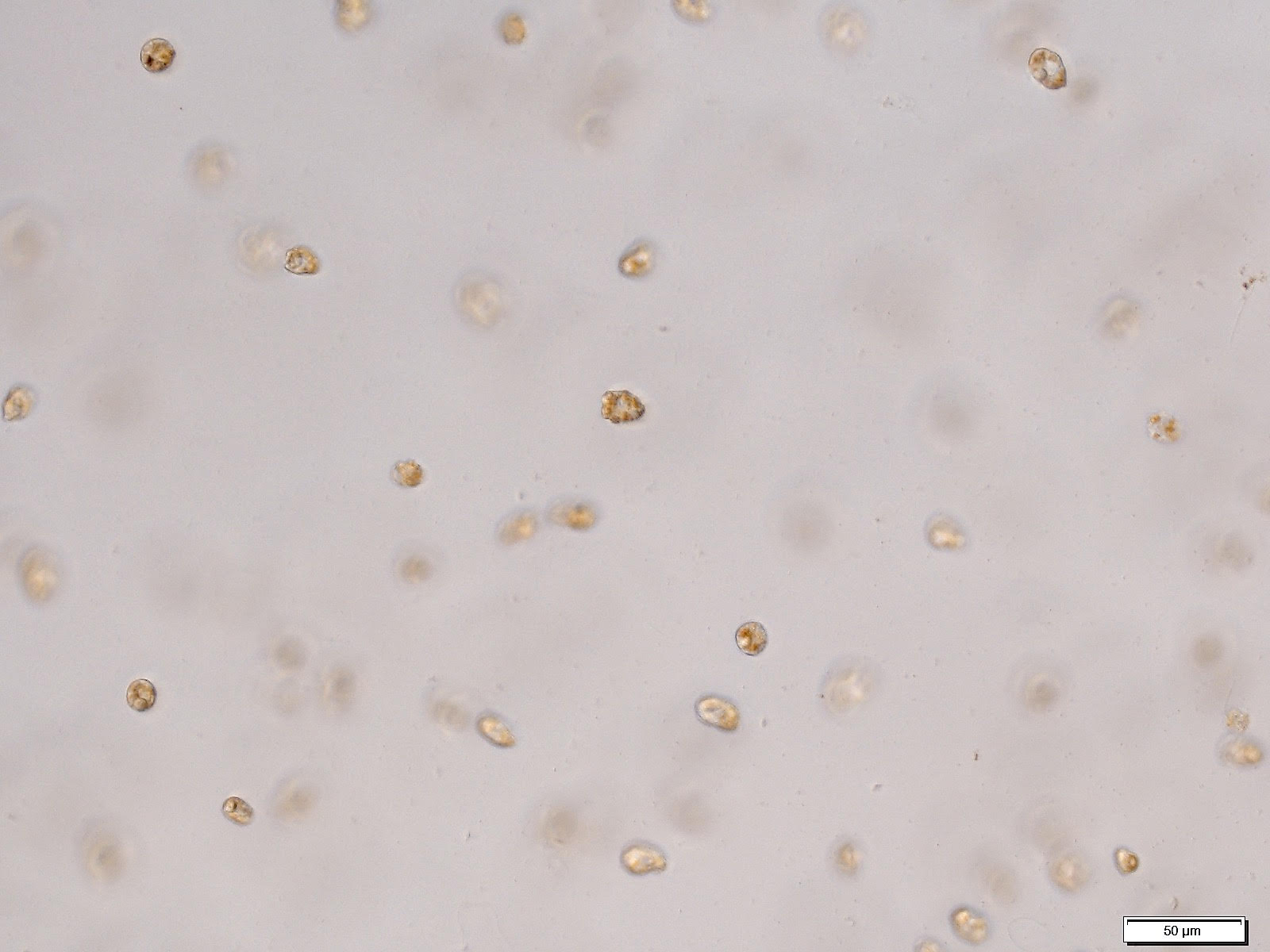

Heterosigma akashiwo, the protist that devastated the Bay last year, was previously considered a “species of low concern,” showing that even an under-the-radar species can wreak havoc under certain conditions—and that San Francisco Bay is not immune to megablooms.

Now experts fear that HABs in the Bay could become more frequent. What’s at stake, says Wren from San Francisco Baykeeper, is the health of the Bay. “Our fisheries are already in dire straits,” Wren says. “And they can’t really handle much more acute shots like this.”

What will it take to reduce nutrients?

Reducing nutrients isn’t easy. It would require major infrastructure rehauls that a 2018 report estimated would cost $10–15 billion across all the Bay Area’s treatment plants. This would likely raise water bills for Bay Area residents. Federal funding for infrastructure improvements and climate change solutions, including through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act, could potentially help pay for wastewater upgrades, though accessing that money is not straightforward. “In theory, we could go after these funds, if and when they’re made available, but it’s definitely not a slam dunk,” says Fono.

Currently, wastewater treatment plants convert ammonia from urine into nitrate, and then the nitrate goes into the Bay. One possible upgrade is to install tanks where nitrate can be converted into gaseous nitrogen, which would then disperse into the air.

In 2021, the Sacramento Regional Wastewater Treatment Plant completed a multibillion-dollar upgrade that successfully reduced its nitrogen discharge by two-thirds. Bergamaschi’s research team studied the water quality in the river by the plant before and after the upgrade, and found that water quality did improve—but only near the plant.

Yet Bergamaschi says upgrading wastewater treatment to reduce nutrient pollution is nonetheless an essential next step in preventing more blooms. “If we want to ensure that we’re protecting our aquatic ecosystems in the Bay, we have to at least take some sort of nutrient mitigation approach,” says Bergamaschi.

Because wastewater treatment improvements will be so expensive, Fono, of the wastewater agency coalition, is determined to promote projects with multiple benefits, including so-called “nature-based solutions.” Specially designed wetlands could filter out nutrients while providing wildlife habitat and protecting communities from flooding or sea-level rise. Palo Alto and Hayward’s wastewater plants are working on pilot projects that incorporate wetlands into their treatment systems.

The Bay Area needs new treatment technology, Fono says, to handle its nutrient pollution sustainably and keep up with the Bay Area’s high-density urban population.

“You can’t tell people to stop peeing,” says Fono. “What I would urge in terms of a call to action is to understand where your wastewater goes. And if your agency has the opportunity to implement a solution that brings your community multiple benefits, especially in terms of climate change resilience, then support that in any way you can through the public process.”