The Panoche Hills are easily overlooked. Nestled between I-5 and the Diablo Range, about two hours southeast of San José, they seem to be just another set of dry, dusty hills. To biologists, though, Panoche is one of the few remnants of the San Joaquin Valley’s past. While agriculture and energy development has overtaken the rest of the Central Valley, Panoche’s shrub grasslands are a refuge for species that have been forced out of their homes elsewhere. Here live elusive blunt-nosed leopard lizards, on the federal endangered species list since its inception in 1967. Here live giant kangaroo rats, who drum their feet in the middle of the night, and dust-colored San Joaquin kit foxes, the smallest dog family-members in North America. This is golden eagle central, too. A little higher in latitude and elevation from the Central Valley, it’s also one of the few places where animals might be able to cool down when climate change pushes temperatures up—the “last bastion in the Northern San Joaquin Valley,” as one biologist told me.

Like millions of other I-5 drivers, I had passed by Panoche for years, driving from my home in Berkeley to the Mojave Desert to research my dissertation on the history of land use conflicts. I thought that the desert was the epicenter of off-road vehicle conflict as the primary location where dirt bikes and jeeps could run free. But the archives had led me, surprisingly, to Panoche instead. For there, in the 1960s, far from the desert where most dirt bikers rode, one of the most dramatic conflicts in the history of off-road vehicles (ORVs) took place. And this was a showdown that shaped the future of recreation on public lands.

In my interviews with land managers, dirt bikers, biologists, and people who hang out at Panoche, almost no one who I talked to had heard of the conflict in the Panoche Hills that shaped off-road vehicle history. But in forgotten reports and government archives, I found that Panoche was a laboratory for testing ORV management practices—and a specter that haunted decision-making about off-road vehicles during the 1970s and into the 1980s. It was the site of a conflict between ranchers and dirt bikers that tested the limits of collaborative approaches to land management. And it was the moment when the U.S. Bureau of Land Management realized that it had to manage people, as well as land. Panoche shaped a rural agency that had been concerned mainly with grazing and mining, putting it at the center of an urban recreation problem that it would be stuck with indefinitely.

When I drove to the Panoche Hills from Berkeley, I was following in the tracks of Bay Area dirt bikers from 60 years ago. Before World War II, dirt biking competitions on El Cerrito’s Motorcycle Hill and in Oakland had attracted up to 50,000 spectators and acres of cars. But after the war, new houses and people began to fill in the bikers’ old haunts. Neighbors complained about the neighborhood riders, including noisy fraternity boys who gunned their engines “loudly—very loudly”—according to a newspaper article from the time—both on- and off-road in Berkeley. Competitions moved farther out, to Lafayette, Dublin, and Orinda.

According to Cycle News, a major West Coast motorcycling publication, riding in the Panoche Hills began with one man: John Gale, Jr., who discovered the area just after World War II. His friends called the 33,000 acres managed by the Bureau of Land Management “John’s back yard.” Many weekend riders soon followed suit.

Or so the story goes. This likely apocryphal tale of one man finding his own place to ride fits the stereotype of dirt bikers as individualistic and not exactly community-minded. But it also reveals a fundamental reality about the sport in the postwar era: there were no rules governing where dirt bikers could go, and often no fences blocking off lands. As Larry Stewart, a Bay Area motorcyclist who began riding in the late 1960s, put it, “you just saw a dirt place and rode your bike there.”

Controversy traveled with these motorcyclists. Other people were also looking to escape rapidly growing cities and their office jobs. As early as 1950, locals complained in The Fresno Bee about littering and hill-climbing tracks in the Panoche Hills, accusing motorcyclists of having “contempt for Nature and no concern for those who might later wish to picnic there.” Although someone else confessed and apologized for leaving their picnic supplies there on a windy day, the newspapers knew that it was already common sense to blame motorcyclists.

By 1953, the Fresno Motorcycle Club began hosting field meets and hill-climbing competitions in the Panoche Hills. By 1955, the annual event grew to 50 participants and 1,500 spectators, with riders coming from across the state and even Nevada. The race started attracting more motorcyclists to the area, especially because of the relatively few winter-accessible public lands in Central California. In 1963, one “two wheel addict” interviewed by The Fresno Bee said that the hills “are considered one of the best playground areas anywhere for motorcyclists.” Riders would either ride their vehicles over to the hills and tool around, or tow their bikes for a weekend of camping, trail-riding, and hill-climbing.

The hills were owned by the Bureau of Land Management. But the flatlands surrounding them were used by ranchers, who grazed their cattle and sheep on their own and BLM’s land. And when droves of motorcyclists began appearing in the early 1960s, ranchers were the first to respond.

They had long allowed hunters and other recreationists to cross their property into the public lands. For a while, it seemed like motorcyclists would be treated in the same way. But in 1963, one of the ranchers decided to close his gates “when several head of his cattle were stampeded over a bluff and killed by motorcyclists,” The Fresno Bee reported. By closing his gates, he also closed off access to the public lands behind him.

In 1966, sheepmen asked for a motorcycle ban in the coast range after the “malicious destruction” of their lands and livestock. Even worse, one of the members of the association “was manhandled by irate members of a motorcycle group,” the Bee reported. To no one’s surprise, two sheepmen asked for the permanent closure of Panoche and the nearby Silver Creek area to motorcyclists after two motorcycle-ignited fires the following summer.

In late 1967, one of the companies in the southern Panoche Hills decided not only to fence in their lands, but also hire armed guards to prevent motorcyclists from accessing the popular Silver Creek area. They posted signs that are still intact today.

Motorcyclists, in response, simply moved their fun to the northern part of the hills, where BLM had built a new road to allow access to the public lands without bothering the ranchers—in theory.

After tensions rose, sheriff’s officers in Fresno and San Benito County redirected motorcyclists to the new access road and a 14-mile trail constructed by the Central California Trail Riders Association. One motorcycle meet that had been planned for the Silver Creek area was redirected to the northern Panoche Hills plateau “to avoid an explosive situation,” as a 1968 government report put it. But after the event, cattlemen and the Trail Riders Association still complained about the ruts and erosion in the area.

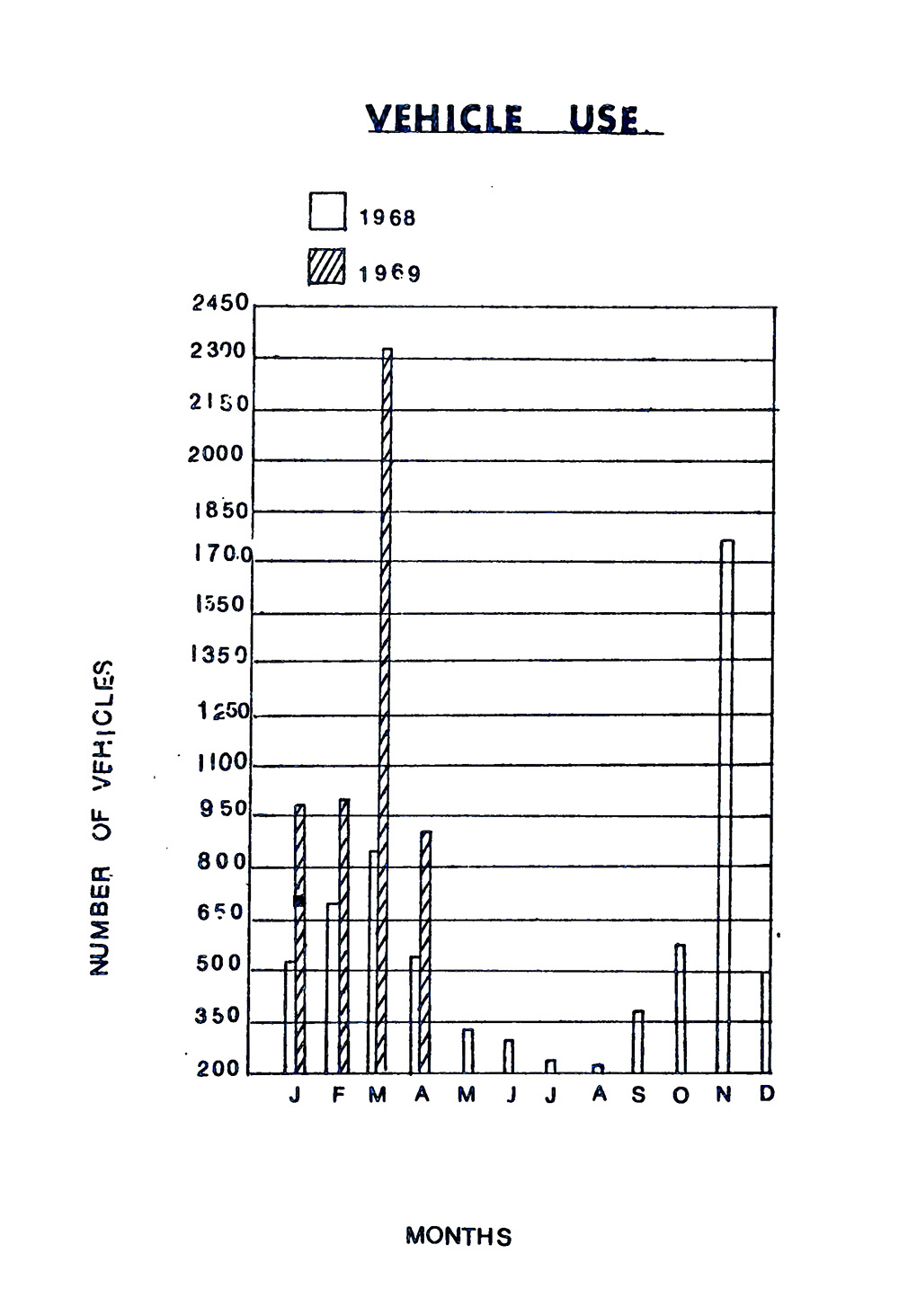

Meanwhile, dirt biking’s popularity was soaring. BLM estimated that off-road vehicle use in the Panoche area increased at least tenfold between 1965 and 1969.

In 1969, manufacturers estimated that there were half a million dirt bikes in California. The question was what the BLM would do about them.

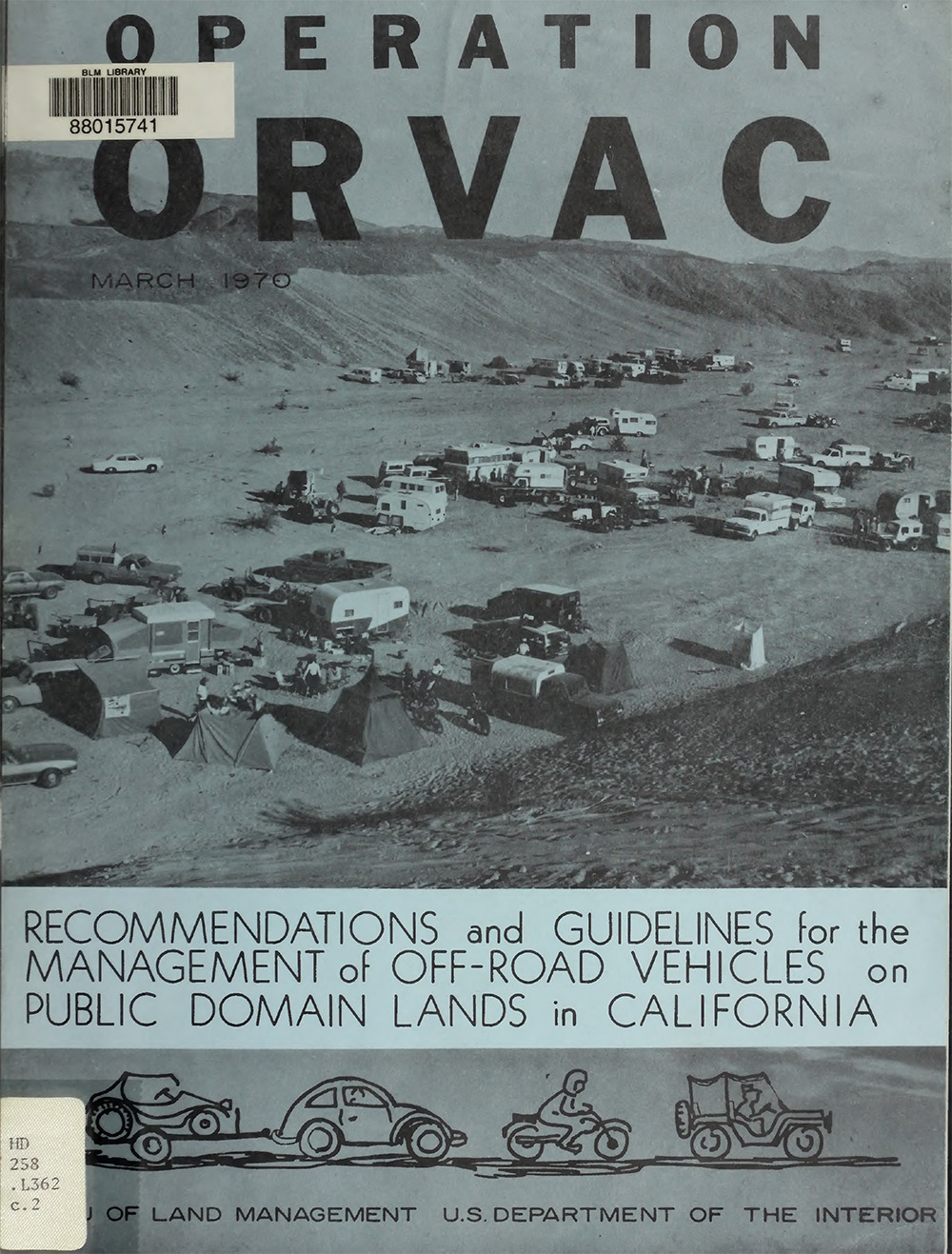

That’s when the agency formed a new group: Operation ORVAC, the Off-Road Vehicle Advisory Committee). Operation ORVAC was part of a broader move toward citizen participation in planning, bringing together representatives of off-highway vehicle groups, conservationists, land managers, and ranchers into a single committee. It was not the only such committee—for example, San Benito County formed the Subcommittee on Motorcycle-Livestock Problems—but it was the highest-profile and most powerful. Reflecting on his experience later, Bill Holden, a devoted volunteer and founder of the Sierra Club Desert Committee, would describe his feelings about the BLM during this period as one of “grudging admiration for the skill and self-control of the bureaucrats in dealing with two difficult publics (i.e., irate conservationists and scientists on the one hand an [sic] ‘mad as hell’ ORV operators on the other).”

Operation ORVAC members discussed an interim plan for Panoche that would be one of the first to restrict motorcycle use to certain areas and seasons. Under the plan, they would label open and closed areas, create trails where motorcyclists could ride cross country, and produce a brochure that specified the rules of the road. And they knew it could shape policy across the state.

As Operation ORVAC members quickly found out, not all motorcyclists followed the rules. As Ray Talbot, the Wool Growers Association representative on the committee, put it, “If you have 500 men up there and there can be 490 of those fellows who are doing a perfect job and being very responsible people. But 10 of them can throw the whole thing, and a trail like that without proper enforcement is no trail at all.” In other words, the problem was enforcement.

The BLM had no rangers back then, and no way to enforce their own regulations. Without cooperation from both the motorcycle groups and the individual cyclists, it was impossible to manage. By the end of the year in 1969, BLM district manager Delmar Vail estimated that only 30 percent of users remained in the designated areas because of “an attitude in users that they should all have the area with no restrictions.”

In 1970, the area was closed permanently. A plan to create an orderly off-road vehicle use area through collaboration and cooperation had resulted in a closed gate. Operation ORVAC chairman Howard Harris, a rancher in San Benito County, gave the postmortem: “the sad realization came at last—without people to enforce rules, without proper sanitation and service facilities, management was impossible, and Panoche Hills has been closed indefinitely.” Ron Sloan, the American Motorcyclist Association representative, said, “Panoche should never have been opened in the first place – period. We are living with a dead horse.” Sloan framed Panoche as a uniquely bad situation, and hoped that land managers would simply forget about it.

But Panoche haunted off-highway vehicle management for years to come. For a couple of years, it remained the only area that BLM closed outright to motorized vehicles, and the closure weighed heavily on off-road vehicle enthusiasts. A sports columnist wrote that the closure of Panoche Hills was just “the start of the squeeze.” Russ Sanford, a representative of a motorcycle group, in his Cycle News column, wrote of another area, “[I]f we screw-up like we did at Panoche Hills, we would be hard-pressed to find any sympathy from BLM or other land-use agencies.” For decades to come, motorcyclists would be stuck with the “one-percenter” problem: that the most radical riders overshadowed the ordinary cyclists who obeyed the rules and stayed on the trails. As Jerry Harrell of Operation ORVAC put it, “Cooperative citizens and a management plan are not enough.” The future of ORVs, in the eyes of the government, was what Diana Dunn called “the Dismal Cycle” in a park managers’ magazine: ORV riders take over an area, enrage other users, come to a self-policing agreement, fail to uphold the agreement when “bad apples” intervene, and wait until the “final straw”—getting kicked out completely.

Panoche became emblematic of how hard it was to manage urban people on public lands—and just how destructive dirt biking could be to local environments. Where motorcyclists rode, the grasslands went bald—reports published in the 1970s and 1980s showed that 60 percent of Panoche’s vegetation in dirt biking areas was lost as a result of riding. That loss would have significant effects on erosion and wildlife habitat. For decades to come, Panoche became a key case study for researchers and government officials studying the “extremely touchy” issue of off-road vehicles on public lands.

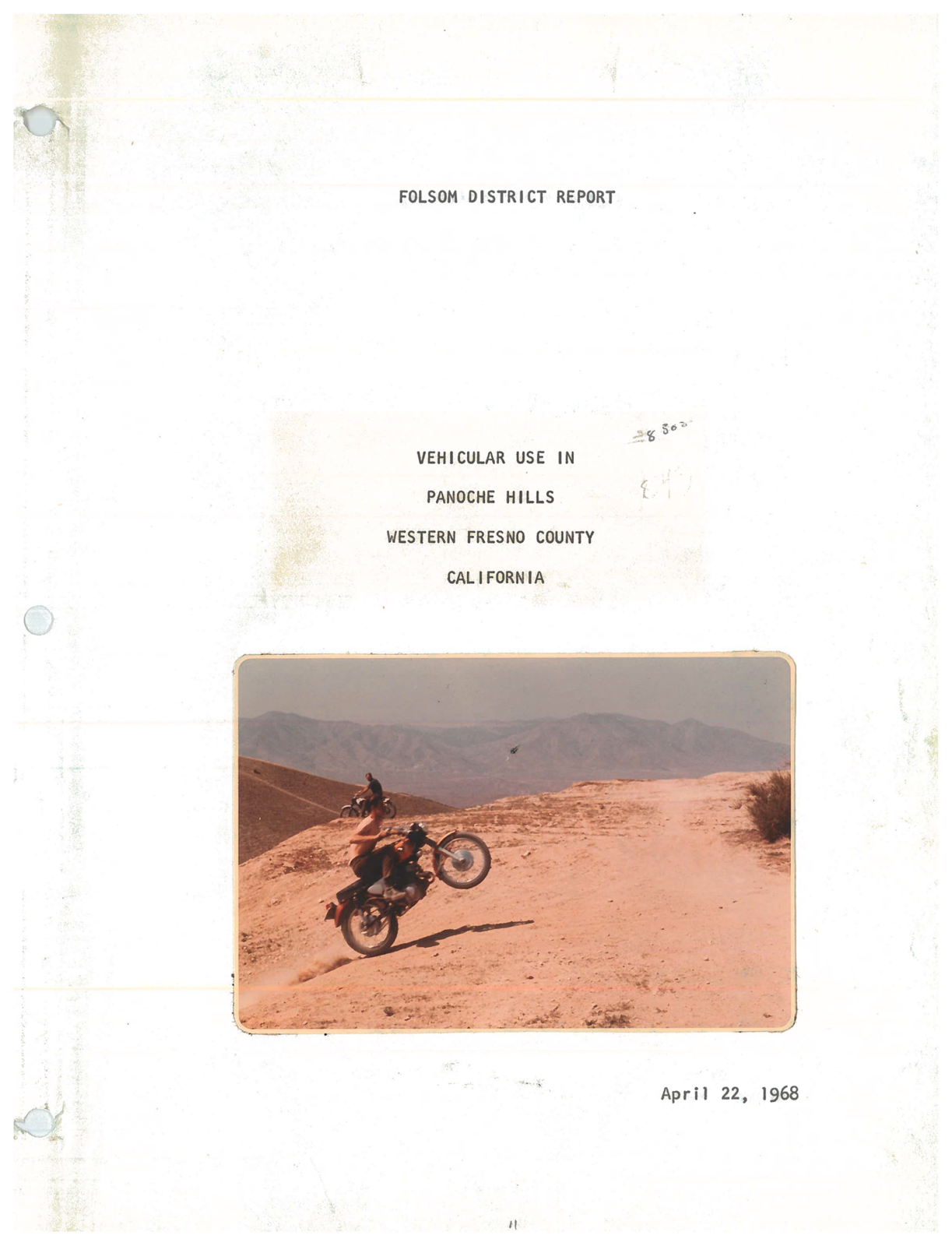

When we went down to Panoche Hills in January, I took the April 1968 report that BLM published. The cover photo, of a dirt biker hill-climbing, encapsulated both the fun of dirt biking and the negative impacts that dirt bikes have on the soils of the Panoche Hills. Inside, yellowed images of the hills that looked like artful landscapes were, in fact, documenting erosion from motorcycles. The photos I found most compelling showed BLM employees out doing fieldwork, attempting to measure the erosion in the hills. Standing with black-and-white painted rulers, they stood on the steep inclines that dirt bikes climbed, showing the human scale of how dirt biking had changed the hills.

Images from the 1968 federal report.

Section maps in hand, my partner—who was taking pictures—and I sought out the spots where these photos had been taken 55 years ago. Our last stop was Silver Creek, which has been closed officially for almost sixty years. Today, it is one of the best places to watch for wildlife in the hills. When we arrived before the sunrise, we found coyote and mountain lion tracks in the mud next to Silver Creek, which was running after the storms this January. The winter’s rains had made the hills a lively shade of green, which we exulted in even though we knew that the grasses were Mediterranean species introduced alongside livestock in the 1800s.

It didn’t take long to see other traces of human presence in the hills. More recent additions included shotgun shells and forgotten plinking targets, but just as evident were the traces of hill climbs, one of the few tracks that go straight up the hill rather than meandering across it. It reminded me of what an East Bay park ranger once told me about old dirt biking trails. “Once a trail gets established, it’s forever.”

Photos by Evan Darling.

The Panoche Hills aren’t untouched nature—if that exists—but they are still valuable. They have weathered an extraordinary amount of change since the dinosaurs left and the blunt-nosed leopard lizards arrived. Today, Panoche is one of the last remnants of a landscape that elsewhere has been overtaken by farmland and solar panels, even as the dirt biking scars remain. Animals and plants have adapted to an environment shaped by these human conflicts. As climate change promises to heat up the hills, however, the question is whether the blunt-nosed leopard lizards and kangaroo rats will be able to survive the next onslaught from our species.

-300x69.jpg)