I’ve heard that the daddy longlegs in my apartment are the most venomous animal on Earth, but their fangs cannot penetrate our skin — is this true? -Antwon, Oakland

The short, most likely answer to your question is no. But there’s a longer, more scenic answer. For that, we’ll have to back up a bit.

First, we need to be clear on which species we’re talking about. “Daddy longlegs” is a common name, and common names aren’t standardized across regions, languages, or cultures. For example: puma, cougar, mountain lion, wildcat, catamount, panther, and even painter can all refer to the same animal – Puma concolor. This is why every recognized species is classified by a binomial name (sometimes called a scientific name). The binomial name consists of two words – the genus and the specific name representing an individual species as we currently understand it. These words were traditionally Latin, but may now come from a variety of languages and contain proper nouns. One advantage of using this system of nomenclature is that the name is standardized across all languages, and we can all agree about the organism to which we are referring. Puma concolor is “the uniform colored cougar,” regardless of how local people may refer to the animal.

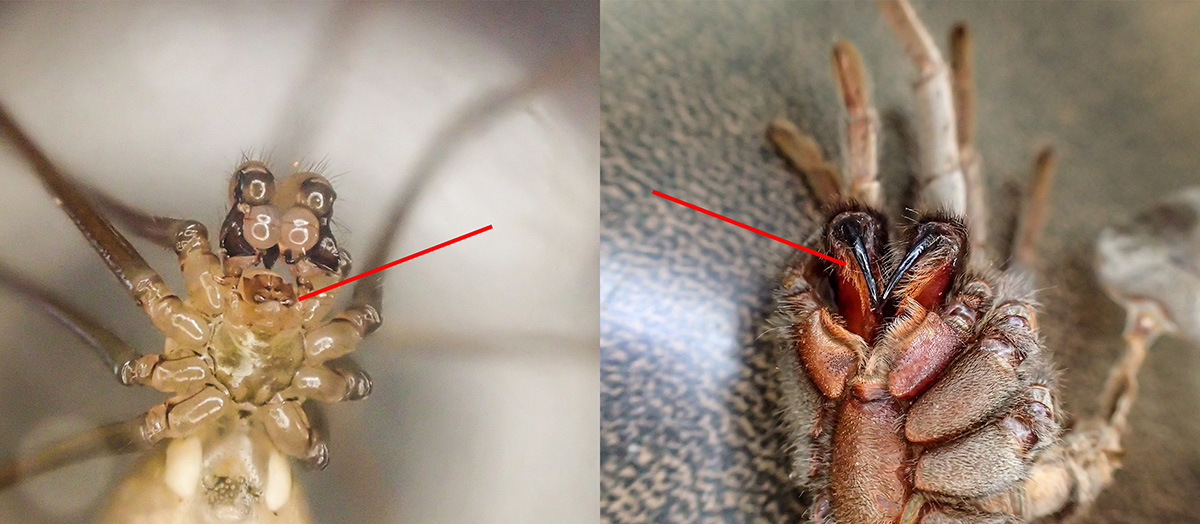

Returning to your question, the organism to which you are referring will change the answer … a little. Where I grew up in the Southeastern United States, the term “daddy longlegs” refers to a group of arachnids in the order Opiliones, often called harvestmen. They are different from spiders; their body is made up of a single pill-like segment, two eyes, and eight legs. While they frequented the basement of my childhood home, it is less likely to find them living in an urban apartment. In the unlikely event that this is the creature you’re asking about, the answer is no – Opiliones subdue their prey with their legs and jaws, and there are no known venomous species.

In some communities, “daddy longlegs” refers to yet another group of animals — large flies in the infraorder Tipulomorpha. These flies, also called by the misleading common name “mosquito hawk,” are characterized by a slender three-segmented insect body with six very long, thin legs. The irony of this group and its collection of common names is that many Tipulomorphs emerge from their pupal phase as an adult with no functional mouthparts, meaning they can neither eat mosquitos nor bite humans. And they certainly aren’t venomous. Strike two.

Our last candidate for “daddy longlegs” are true spiders in the genus Pholcus. In California’s Bay Area we have one commonly observed species: Pholcus phalangioides, also commonly called the “cellar spider.” This spider is synanthropic, meaning it benefits from living near or with humans. It now travels the globe with us, and can be found on every continent on Earth except Antarctica (although I suspect they can be found lurking in the dusty corners of research stations there). This is most likely the animal to which you are referring, so let’s get down to answering your question, finally.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

*Brown recluses aren’t the most venomous spider in the world either, they were the most venomous spider in a particular study comparing venom toxicity. Worry not, they are not a native California spider.

Cellar spiders, like most spiders, possess both fangs and venom glands. However, they typically immobilize their prey not with venom but with silk, using their long legs to manipulate their silk and ensnare prey. In addition, research has shown that these spiders have relatively weak venom. One study concluded that the venom of P. phalangioides was only 1.9 percent the strength of brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa) venom*, meaning cellar spiders are far from being the most venomous spider in the world. When we combine these data points with with a lack of medical case reports of bites from this species, the evidence indicates that cellar spider venom poses no medical danger to human beings. As for their fangs, they are greatly reduced compared to other spiders of similar size, measuring around a quarter of a millimeter in length. Human skin varies in thickness, from a half a millimeter up to 4 millimeters. So while the fang could potentially penetrate and envenomate your epidermis (which would still be considered a bite), they are too short to fully penetrate human skin – and I can’t imagine why this relatively shy spider would attempt to do so.

In addition to being rather harmless to people, cellar spiders are quite beneficial to have around your house. They have a particular fondness for preying on moths, mosquitoes, and other household pests, and thanks to those long legs and silk-throwing abilities, they are able to overpower other insects many times their size. While their dusty, erratic webs may look messy in the corner of your house, give the cellar spiders a chance and I think you’ll find they make excellent housemates.

Ask the Naturalist is a reader-funded bimonthly column with the California Center for Natural History that answers your questions about the natural world of the San Francisco Bay Area. Have a question for the naturalist? Fill out our question form or email us at atn at baynature.org!