This is a series on NatureCheck, a scientific collaboration looking at indicator species to assess East Bay habitat. You can read the full report here. (Illustration by Jane Kim)

Other STORIES IN THIS SERIES

How Healthy Is the East Bay’s Habitat? An intro to NatureCheck, and how you can help.

The Wildlife-Rich Grasslands Checking in on ground squirrels, tiger salamanders and golden eagles.

What Bats Tell Us Meet the Bat Brigade, looking out for the East Bay’s 16 bat species.

The NatureCheck network’s collective lands and particular focus area include four watersheds—Pinole Creek, Wildcat Creek, San Leandro Creek, and Alameda Creek—that together account for more than 700 square miles of riparian habitat, from rocky headwaters to ephemeral and perennial streams to the wide and slow-flowing depositional areas closer to San Francisco Bay. According to NatureCheck, California has lost more than 90 percent of its riparian habitat to urban development and water diversions, making these habitats increasingly important. Climate change is also altering hydrological conditions in watersheds by warming water temperatures, increasing the frequency and intensity of droughts, and causing dramatic and unseasonable rain events.

East Bay watersheds aren’t immune to these changes, of course. For example, while its upper reaches are relatively undisturbed, Alameda Creek’s lower reaches have been dammed and diverted into a series of reservoirs and flood control channels. Wildcat Creek once lost all of its rainbow trout due to urban development, until it was restocked in 1983 with fish from the San Leandro Creek watershed. Despite the striking changes, annual surveys conducted by network agencies continue to show that these watersheds, even Wildcat Creek, continue to support native fish, including Sacramento pikeminnow, Pacific lamprey, and, perhaps the most iconic, the rainbow trout.

Steelhead/Rainbow Trout

Oncorhynchus mykiss

If you want to see a textbook example of “undisturbed” habitat for rainbow trout in the East Bay, Bert Mulchaey, the supervising fisheries biologist for the East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD), suggests driving Pinehurst Road along the northern edge of Reinhardt Redwood Regional Park. Though San Leandro Creek flows here behind a barbed-wire fence marked “Protected Watershed, No Trespassing,” you might catch a glimpse of the clear water babbling over gravel beds, shaded by an understory of sword ferns and brambles and an overstory of bay trees, live oaks, and coast redwoods. Here, a trout will find all it needs to be at home: shaded, cold water with dissolved oxygen, gravelly riffles to build nests and deposit eggs, still pools to rear young trout, and the ability to migrate down- and upstream.

Incidentally, this creek isn’t far from where the rainbow trout was first documented by scientists in the United States. In 1855, shortly after California became a state, naturalists from the newly founded California Academy of Natural Sciences, now known as the California Academy of Sciences, pulled specimens of the fish from Redwood Creek, near the present-day southeast entrance of Reinhardt regional park. William P. Gibbons, the academy’s founder, named the species “rainbow trout” for its iridescent scales that faded from bright pink to a deep dark olive green. Long before that, however, this fish fed the area’s first inhabitants. Ohlone and Delta Yokuts peoples often built villages near streams for their ready supply of fish.

But freshwater streams tell only half of this species’s story.

Oncorhynchus mykiss goes by two names, depending on the fish’s life history. Rainbow trout and steelhead are the same species, but steelhead, unlike rainbow trout, are anadromous: after they hatch, steelhead navigate the treacherous odyssey from their home freshwater stream to the Pacific ocean. Those that survive the journey live at sea for up to three years, sometimes traveling thousands of miles and growing up to 55 pounds off forage fish and crustaceans, before returning to their home streams to build nests and spawn. Some rainbow trout also migrate within their freshwater stream. “Adfluvial” rainbow trout in Redwood Creek, for example, might migrate to the Upper San Leandro Reservoir, where they spend their “ocean” stage eating aquatic insects and nourishing predators like blue herons and river otters.

As a biologist and an author of the section in NatureCheck on the species, Mulchaey sees O. mykiss as a great indicator for East Bay watersheds according to two metrics: habitat quality and the presence of anadromous trout. Even though rainbow trout can still be found throughout the East Bay, the Central Coast population of steelhead has been listed as federally threatened under the Endangered Species Act since 1997.

As drought and urbanization stress habitats and cut off fish migration, network agencies are working to improve conditions for O. mykiss—by daylighting creeks or removing migration barriers. For instance, EBMUD recently participated in a fish passage improvement project on Pinole Creek, making it the only watershed of the four that supports anadromous steelhead. The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission and Zone 7 Water Agency will also soon unveil a new series of fish ladders on Alameda Creek to allow for steelhead passage.

“That’s another focus of NatureCheck, other than determining the health of this species,” says Mulchaey. “It gives an indication of what we need to work for, and where we need to focus our efforts if we want to have these species around for the long haul.”

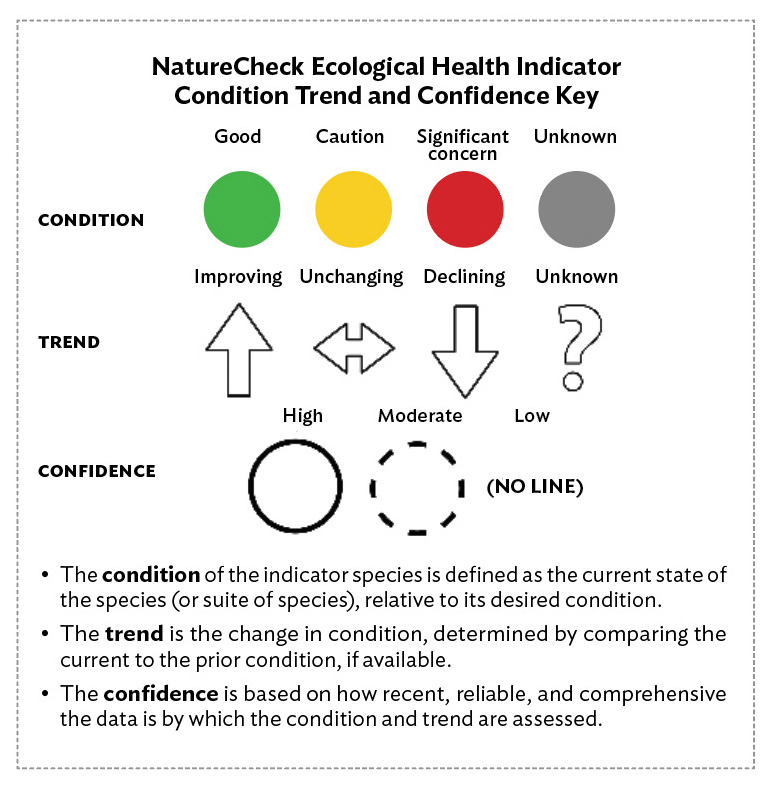

Species condition for rainbow trout/Steelhead: