As I arrived at the Port of Oakland, a high-tech nautical mud abduction was underway.

On a cherry-red dredger, a 55-cubic-yard clamshell bucket hung from a crane by a webbing of cable, like a 45-ton chandelier. With open jaws, the bucket descended into the water, sank to the harbor floor, closed over a thick scoop of sludge, and lifted it into a massive transport barge.

It was just tipping sunrise; sleepy pelicans dotted the riggings and mooring lines of the harbor. The dredger, named the Njord after the Norse god of the sea, runs 24 hours a day to meet its production goals; this crew had been scooping and dumping since midnight. By the time the sun popped over the top of the Oakland hills, the barge was almost fully loaded with 2,700 cubic yards—about 5,000 tons—of soupy sediment. The dredger moved on to the next section of harbor, scooping up bucketfuls of mud, tracing long, clean lines like a methodical lawnmower.

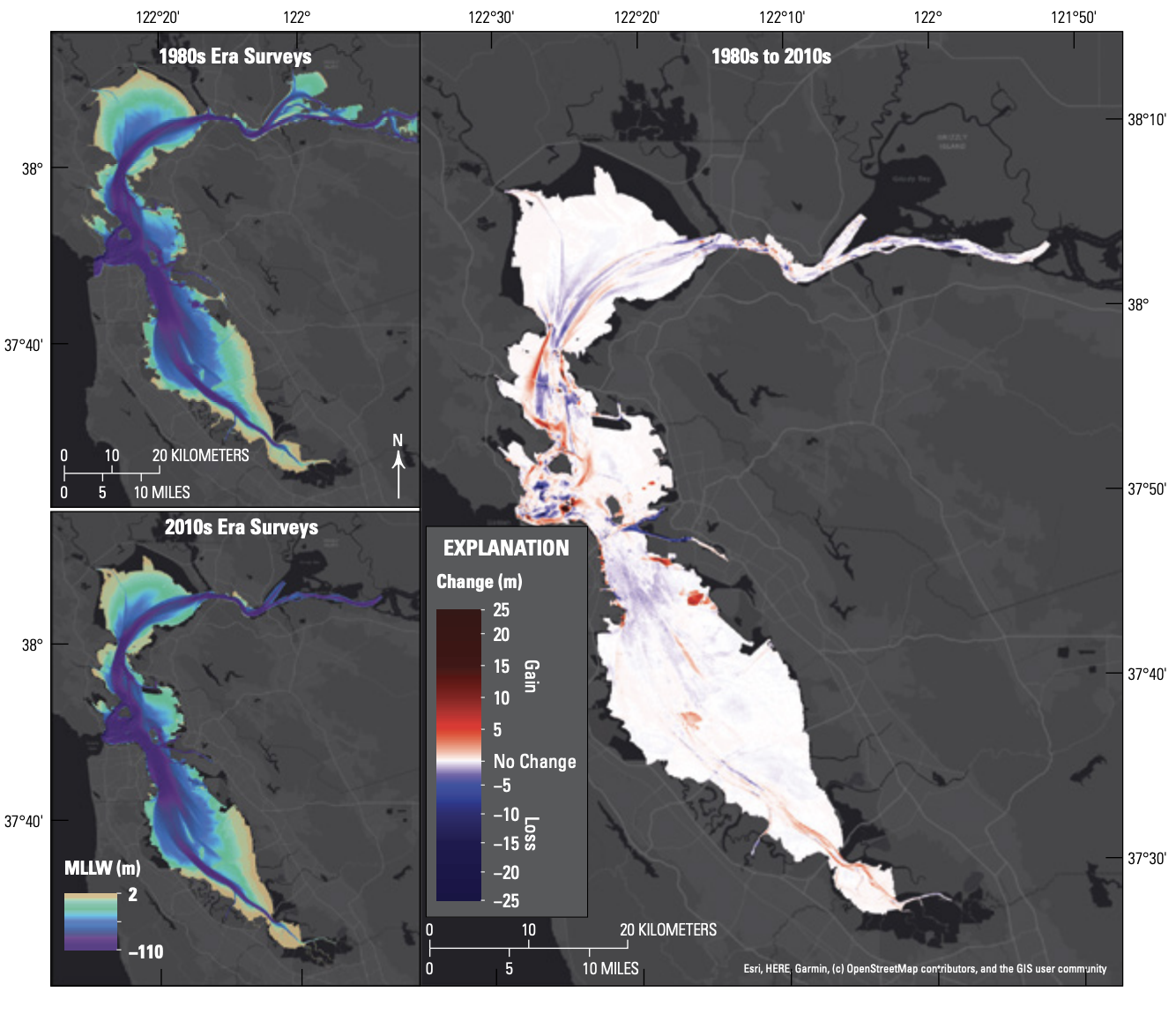

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredges an average of 2 million cubic yards of sediment from around San Francisco Bay every year to maintain the federal navigation channels that allow gargantuan freighters to traverse it. Manson Construction Co. Capt. Joe Barney, who has been dredging for 38 years, puts it this way: “We just keep the channels clean so the ships can get in so you can go shopping.”

When cargo ships get bigger, the channels must be made deeper and wider. This should be great news for the Bay Area’s mud-hungry wetland restoration projects. Over 150,000 acres of tidal marsh have been lost due to human development. Much of that former wetland has subsided—in some places, up to 15 feet—from being diked off, drained, and grazed on.

About this project: Bay Nature is reporting on funding for nature in BIL and IRA. Tell us what you think or send us a tip at wildbillions@baynature.org, and read more at our Wild Billions project page.

If they aren’t replenished with massive quantities of sediment, they will be swallowed by the ever-rising seas. But because of a federal rule, most of the mud dredged from the Bay hasn’t reached a wetland. For decades, Captain Barney has had to barge tons upon tons of that precious sediment out to an open-ocean dump site and drop it off the edge of a 8,000-ft underwater cliff.

Now, $19 million from the 2021 federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) is helping restoration projects perform an emergency mud transplant. The funding is subsidizing “beneficial reuse” of sediment in the Bay Area: bringing in mud dredged from the depths of the Bay to save our wetlands from drowning.

“Mud isn’t typically very sexy,” Christina Toms, an engineer with the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board, told me. “When you think about all the pejoratives, the implication is dark, murky, unhealthy, bad.”

But talk to a few wetland ecologists and geomorphologists, and mud becomes magical. It’s a pivotal, limited resource. It’s the backbone of the Bay itself. And the need for mud—or more formally, sediment—is urgent. For Bay Area wetlands, sediment supply is the difference between life and death.

“We love mud in our world,” said Toms. “Maybe we just need to start putting that on t-shirts and billboards. You know, ‘San Francisco Bay hearts mud.’”

Sediment and water are the fundamental ingredients in the primal potion that builds the coast. Rivers, streams, and washes of rain carry tiny payloads of soil, silt, and sand through the watershed until they meet the sea and deposit their cargo onto a subtidal habitat. Slowly, the sediment builds up, creating a tidal mudflat fizzing with mollusks, crustaceans, and worms. The mud builds up a little higher until it creates a salt marsh, half-submerged, thick with pickleweed and saltgrass that hold the marsh in place with reaching roots. Flat-faced California halibut swim in from the deep sea to spawn, releasing eggs that drift and settle on the wetland floor. On sandy verges, least terns scratch out nests and decorate them with pebbles. Ultimately, a spectrum of wetland ecosystem develops, all built from mud: the humble starstuff of the Bay.

Due to rising sea levels and the meddling of human development, that muddy magic is going awry. The balance between sediment and water is off. We have disconnected our wetlands from their watersheds, cutting them off from natural sediment deliveries. A 2015 report from the multi-agency Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals Project calculated that diked baylands need to be reconnected to the tides by 2030 for them to have a fighting chance of keeping pace with sea level rise. Healthy wetlands can buffer coastal infrastructure against flooding and storm surges, a superpower that will come in handy as weather becomes more extreme. But if they aren’t built back up to the right elevation in time, those vital ecosystems could go the way of Atlantis.

“We’re pretty close to 2030, and we have a long way to go,” says Julie Beagle, an environmental scientist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ San Francisco District. “We’re not going to get there in the current paradigm.”

Wetlands circa 1800, versus 2015. Vast amounts of San Francisco Bay’s wetlands (shown here in green) have been diked, developed, or turned into grazelands, as maps from the San Francisco Estuary Institute’s 2021 Sediment for Survival report detail.

Pairing dredged sediment with a compatible reuse site is tricky. There’s even a “dating site for sediment” called SediMatch. Like all dating sites, it’s hit or miss. Sometimes it’s a case of right mud, wrong time—dredgers can’t afford to store sediment, so the reuse site needs to be able to accept it in the right window. Sometimes the sediment is too contaminated. Often, the rendezvous is just too expensive.

A longstanding Army Corps regulation compels dredging projects to dispose of sediment using the “Federal Standard”—the cheapest option that is still environmentally acceptable and consistent with sound engineering practices. Trouble is, placing sediment on a wetland is usually $10–$20 more expensive per cubic yard than dumping it, because the mud has to go farther, and because offloading is more work than dropping it out of the bottom of the barge. If the Corps wants to go with a more expensive but environmentally preferable option—like beneficial reuse on wetlands—it can. But part of the extra cost has to be covered by a non-federal partner.

Environmental restoration is a “priority mission” for the Army Corps, alongside navigation and flood control—but for years, politics and economics have stood in the way of changing the Federal Standard. Dredging is funded by a tax on importers of waterborne cargo—who want to see their dollar go as far as possible. For harbor maintenance, that is. “They’re not in the business of environmental restoration,” said Beagle.

In a big win for the wetlands, Congress in 2020 allowed the Corps to cover more of the cost for beneficial reuse projects that help the environment, or reduce storm or flood risks—but prospective projects still must enter into the bureaucratic dance of finding state agencies and conservation non-profits to split the bill.

“The paradigm has paralyzed us,” Beagle told me. “It’s challenging. But we’re overcoming it together.”

Now, the $19 million from BIL is covering the extra cost of sediment reuse, temporarily removing that bureaucratic roadblock.

The funding coincides with a shift in nationwide Army Corps priorities. In January 2023, Lieutenant General Scott Spellmon, Chief of Engineers, sent out a “Philosophy Notice,” a sediment commandment from on high. “Dredged material is a valued resource that is not to be wasted,” he wrote. “Through a symbiotic relationship with navigation dredging, you are being called to generate productive and positive uses of dredged material.”

Historically, the Corps has reused about 30–40 percent of dredged material; Lt. Gen. Spellmon wants to see 70 percent reuse by 2030. In the San Francisco District, where a panoply of agencies are all pushing for beneficial reuse, the Corps is even more ambitious, aiming for 100 percent reuse of suitable sediment. The science over the last several decades has been pointing to the sediment deficit in the Bay, and telling us where all the sediment is, Beagle told me. “And it’s all in the navigation channels.” There’s enough mud in the Bay; some of it is just in the wrong place.

The BIL money “allows us to do beneficial use sooner,” said Arye Janoff, who is a senior project planner working on the Corps’ long-term management strategy for Bay Area sediment. “The sooner we are able to establish marsh plane elevation, the sooner wetlands and marshes can establish.”

The first project to benefit is the Montezuma Wetlands, in southern Solano County, where freshwater outflow from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta mingles with saltwater from Suisun Bay. Unprecedented quantities of dredged mud are making their way to this 1,800-acre restoration, the largest sediment reuse site in California that is currently active.

This time, Captain Barney’s bargeful was saved from the abyssal plain. After a roughly six-hour tugboat ride from the Port of Oakland, the sediment barge, riding low and heavy in the water, was delivered to the Montezuma Wetlands. Montezuma’s offloader, the Liberty, revved up, low electric hum building into a spaceship roar. “The scale blows everybody away,” said Doug Lipton, chief scientist at the Montezuma Wetlands Project. The Liberty is the fastest offloader west of the Mississippi.

To loosen up the sediment, the offloader blasted water into the barge, mixing the mud into a slurry that bubbled and roiled. A giant siphon slurped the black goo into a pipe that flexed and groaned as it whisked the mud across a half-mile of wetland and sent it sloshing out the other end. As the slurry spilled out into its new home, Cell 16, the heavier sediment particles settled out of the mixture, creating a miniature alluvial fan. Slowly but surely, this slice of empty dirt, bounded by levees, will rise to wetland elevation.

For now, Montezuma is a Frankenstein’s wetland, an array of cells in different stages of restoration. Dry squares sit next to half-filled pools wet and busy with birds, which border a 600-acre-section of restored marsh—over 450 football fields’ worth—called Phase I.

In its broad strokes, wetland restoration has the childlike simplicity of digging channels and pools at the shore: take a wetland that’s been diked and subsided, fill it back up with mud, then knock a hole in the dike and let the tides flood in. “We’re sort of playing God by building a field of dreams and hoping it’s gonna work,” Lipton told me. Water and mud, reunited at last, create the scaffold that plants and animals need to claw their way back into the area.

In practice, of course, it’s much more complicated. A self-described “mud doctor,” Lipton has been working on the Montezuma Project for over three decades. In the 1990s, Lipton started making the case that some of the “contaminated” sediment dredged from the Bay, deemed unsafe for reuse at the surface of a marsh, was actually safer buried under a wetland than dumped in the open ocean.

Mud in the Bay contains varying amounts of copper, lead, zinc, arsenic and selenium. It also contains traces of mercury, a souvenir from the Gold Rush, when 19th-century prospectors used quicksilver to precipitate gold out of troughs of sediment. As their leftover mud washes down from the Sierras into the Bay, the mercury rides along.

Lipton and the Montezuma Project were early to argue that we should take advantage of wetlands’ natural abilities. “They concentrate contaminants, filter the water, and put it in the mud.” In those wet, anaerobic conditions, sulfides bind to and immobilize metals like zinc, and organic matter binds up organic contaminants like DDTs and PCBs. Wet mud helps the wetland function as the liver of the ecosystem.

But the mud has to stay wet. Let it dry out, and it can oxidize, creating acidity that can release its poisonous prisoners into the water. The top of the marsh—the “cover material”— can dry out at low tide, so the mud there needs to be cleaner. The deeper part of the marsh, however—the “foundational material”—is always soaked in water. Taking advantage of this, Montezuma has been maximizing the sediment supply by using dirtier mud as foundational material, buried at least three to five feet below the surface.

At first, this plan got Montezuma sued—by “all my environmental friends,” according to Lipton. “No one ever did it before,” he told me. “It made people nervous. Including us.”

Save the Bay, a nonprofit dedicated to Bay restoration, sued the Montezuma project in 1998. “It was a case of first impression,” said David Lewis, Save the Bay’s executive director. “The philosophy behind our litigation was, you need to be super careful.”

After years of research and monitoring, and rigorous outside review administered by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, Lipton’s friends came around—because the project proved to be safe. Once the Phase I segment was flooded, project scientists carefully monitored contaminant levels in the wetland’s waters and in the slough beyond; they stayed well below stringent water quality criteria. “I’m glad the project went ahead,” said Lewis. There were no hard feelings about the lawsuit—Save the Bay has helped the Montezuma project get additional public funding. “We’re succeeding because Mother Nature is the best engineer,” said Lipton. The mud is working its magic.

When it comes to keeping his contaminants inert, Lipton has an unlikely ally: sea level rise. “It’s wreaking havoc, obviously, in other ways,” Lipton said. But “all the stuff we’re burying is actually going to be buried deeper.”

Over Zoom, the Water Boards engineer Toms gave me a historical Google Earth tour of Bay Area wetlands, flying us backwards and forwards in time. A few decades ago, she showed me, wetland restorers were able to target empty, relatively secluded tracts of land. “Those early projects didn’t have these fundamental conflicts with the built environment,” she said. As we zoomed forward in time, parcels of gray, salt-crusted land bloomed into the channel-dappled green of healthy wetland.

The regional target for healthy wetland is 100,000 acres. Currently, the Bay Area has about 45,000 acres of tidal marsh, and 6,000 acres of active restoration sites, according to the San Francisco Estuary Institute. Another 24,000 acres’ worth of restorations are in planning stages. If all of those wetland projects are completed, we’ll still be only three-quarters of the way there, and wetland restoration is getting harder. “We have picked most of the low-hanging fruit,” Toms told me. Now most projects are butting up against human infrastructure.

She flew us over to a recent project at Sears Point, on the north side of San Pablo Bay, that required building a setback levee to protect a rail line and State Highway 37. Near the city of Oakley, the Dutch Slough project had to wait for a canal to be encased in a pipeline to make sure the restoration wouldn’t impact drinking water.

When a wetland is linked with upland habitats, it can respond to sea level rise by shifting inland. Mudflats become subtidal, tidal marsh becomes mudflats, and upland habitat becomes tidal marsh. But most of the tidal wetlands in the Bay have been squared up and divided by the clean, hard lines of highways, pasturelands, and urban boundaries, with no upland to migrate to.

“Since connectivity and heterogeneity drive resilience, and we don’t have those anymore, we have a very vulnerable system,” Toms told me. As land use planners push to meet the final quarter of that 100,000-acre goal, it will be vital to protect transition zone habitat and adjacent uplands, creating ecosystems that blend and flow into each other. As Toms put it, “nature loves mess.”

Our coasts are crowded. Wetland restorers engage with land use planners, transportation planners, utility planners, and so on, at all the agencies that have interests in the shoreline. For example, the ongoing Cullinan Ranch restoration project, a 1,500-acre parcel within the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge, has just over three miles of frontage along Highway 37—necessitating years of meetings and negotiations with Caltrans. According to biologist Renee Spenst, who has worked on the Cullinan project since 2008, Caltrans’ many divisions made building relationships challenging. “You would go to a meeting and there would be 30 or 40 people there, and two of them would be the same as the last meeting you went to,” she told me. “There was a constant re-education process at pretty much every single meeting.” Often, goals and standard operating procedures didn’t mesh. “Is Caltrans at the table? Sure, they’re at the table—but with their lips sealed, or maybe banging their fists,” said Lewis.

In an emailed response, Caltrans spokesperson Vince Jacala acknowledged roadblocks in the implementation of restoration projects. “One major constraint is the transportation project funding cycle,” Jacala wrote—most Caltrans projects “come with a four-year funding timeline regardless of a project’s complexity.” Jacala also said that Caltrans is “actively developing increased partnerships with local land trusts and organizations” and that they have the intention to “conduct early engagement where practicable.”

Toms agrees that early engagement between restoration projects and agencies like Caltrans, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, and PG&E is key. Getting the wetland people, the transportation people, and the utility people on the same page can be a slow process. “You’ve got a lot more players in the room,” Toms said. “You have processes that aren’t used to integrating with each other. And so we’re learning how to work with each other.”

Montezuma just had its best mud year ever. In the last twelve months, federal money helped bring the project over 1.5 million cubic yards of sediment—more than the previous three years combined. “Everybody’s been screaming [that] we can’t keep wasting our state’s geology, that we’re letting the federal government throw our soil out into the ocean,” Lipton told me. For years the Corps was the hardest nut to crack. But now that they’re pushing for reuse, they’re “really doing the best job they’ve ever done.”

“It’s almost like a jazz band,” said Lipton, who plays jazz guitar. “Everyone plays the same head sometimes, and everybody takes a solo sometimes, but we all come together playing the same tune.” Across the many different agencies, organizations, and institutes, there’s finally a consensus that the sediment must flow.

In the first week of the new year, a strange sediment was released just offshore of Eden Landing, a wetland next to Union City: silts sprayed green and magnetized. These painted particles will help the Corps track the results of a new, experimental technique designed to mimic the pulse of sediment that the Bay’s historical wetlands would get after a big storm.

Back when tidal marshes were connected to creeks and rivers, heavy rain would flush a big slug of sediment out of the watershed and over the marsh, blanketing it with a thin layer of mud. Now, that sediment load gets trapped behind dams, or skips the wetland and goes straight into the Bay.

If engineers can simulate that process, it could become a faster, cheaper way to help wetlands keep up with sea level rise. In December, the Corps piloted the technique, called “strategic placement.” Over three and a half weeks, an agency team led by Beagle released bargeloads of sediment in the shallows off Eden Landing and let the sediment pancake down into the water. The hope is that the tides will do the rest, depositing mud onto the wetland just like a big pulse from a storm. “We’re trying to work with water and take the sediment part of the way there,” said Beagle.

Over the next year, the Corps has contracted USGS to see where that sediment travels, leaving magnets in the mud to see how many green crumbs of sediment they catch. “We’re going to observe this phenomenon, and learn from it,” Beagle told me. “What we’re trying to do is find ways that actually bring down the cost of beneficial use. So that we’re not getting rid of the Federal Standard, but we’re making beneficial use the federal standard.”

A barge full of sediment heads in December to Eden Landing, where the Army Corps of Engineers is now testing a new technique that mimics the flow of sediment from heavy rains. (Courtesy of Brandon Beach, Army Corps of Engineers)

On top of the $19 million for mud-moving, another $3.8 million from BIL is funding the Corps’ ongoing Regional Dredged Material Management Plan, which determines the Corps’ long-term strategies and goals for sediment placement. The RDMMP “has many tentacles,” said Janoff—including research into how sediment moves through the Bay, and where it can have the biggest impact—but a key priority is finding creative ways to reuse more sediment.

Toms, at the Water Boards, agrees that experimentation is key—and that we don’t have time to be overly precious about how we move sediment around. After all, wetland ecosystems are designed to be resilient to disturbance. “These plants and wildlife and fish evolved in a messy system that occasionally was full of mud,” she said, “And, like, they figured it out.”

“We are coming upon the breach,” Lipton said, as we approached the part of Montezuma where the Phase I cell was reconnected to the tides three years ago. The area was a vision of what the entire wetland could become eventually, an overgrown jumble of greens, yellows, and terracottas, smelling mossy and fermented. A snowy egret dabbled in an open pool, thigh-deep, and great blue herons peered down at the mud with hunched shoulders. The whole parcel is lush with reeds, saltbush, and pink-tipped pickleweed, buzzing with small mammals and birds. Endangered salt marsh harvest mice, brine-loving rodents found only in the Bay Area, have moved in.

The raised levee we walked down is already being eroded away by the water. Eventually, this part of the slough will integrate naturally into the wetland, a gentle gradient from one habitat to another. As we arrived, the tide was just starting to go out, and water was streaming out of the wetland like a long, powerful exhalation. The remaining levee was covered with a thin layer of half-dried mud that caked into the treads of our boots: new sediment, deposited by a high tide.

Scenes from Phase I, at Montezuma Wetlands. (Kate Golden)

Lipton leaned down and rubbed some of the rich, coffee-colored gloop between his fingers. Crisply captured in the mud were dozens of animal tracks, weaving to and fro across the levee: the uncanny hand-prints of raccoons, countless coyote paws, the triad slices of bird toes, miniscule imprints of rodent claws, and now, our own footsteps.

The fresh mud-blanket is a happy sign that Phase I has been caught up in the flow of the estuarine system, the endless circulation of its water-and-sediment potion. After being given a running start, the wetland may become self-sustaining, growing and shifting around the creep of sea level rise. And when first-rate habitat is made available, native wildlife rushes in like water through a breached levee. Birds were using Phase I the day after the breach; fish were counted within the first month. Rare salmonids have been spotted taking refuge among the rushes and reeds of Montezuma, a place to pause before they leave the rivers of their childhood and venture into the open sea. “Not many,” Lipton told me. “But maybe, over the years, they’ll tell their friends to come.”