[callout]BayNature.org has expanded coverage of these dangerous plant pathogens in an Online Extra: Native Plant Nurseries Get Ahead of Phytophthora[/callout]

Update, July 16: Since publication of the article on new strains of phytophtora in the July-September 2015 issue of Bay Nature, we have learned that the presence of Phytophthora tentaculata on SFPUC lands is more extensive than originally reported. For more information see: Killer Plant Pathogen Is Widespread at SFPUC’s Alameda County and Peninsula Restoration Sites.

arly last year, the San Francisco Public Utility Commission (SFPUC) received a shipment of sickly-looking toyon, a California perennial shrub, from a native plant nursery. The water agency had been planting toyon on restoration sites in central Alameda County as mitigation for the large water infrastructure projects it is undertaking nearby.

On examination, the toyon roots appeared badly discolored and so, as is the protocol in such instances, the agency sent the plants out for testing, and one came up positive for a dangerous, nonnative species of microscopic parasite in a group of organisms named Phytophthora. The discovery has jolted the Bay Area habitat restoration community and could dramatically change the way the native plant industry does business. While nurseries are scrambling to tighten up their safety protocols, some restoration managers, including those at the SFPUC, have begun to shift away from planting seedlings and are instead spreading seeds directly as a safer alternative, a change that could have huge implications for habitat restoration practices.

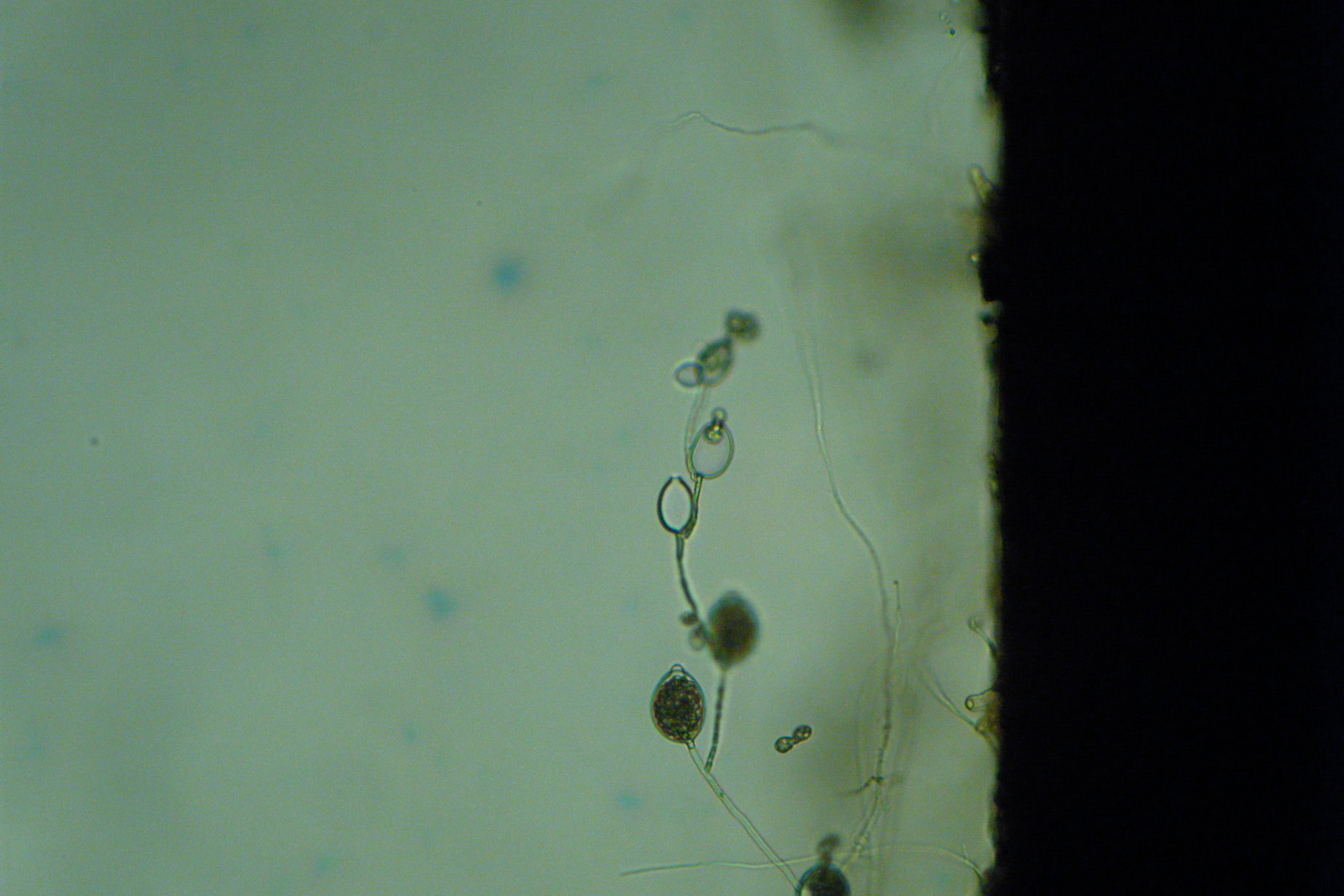

You’ve already encountered species of Phytophthora if you’ve heard of sudden oak death (Phytophthora ramorum) or the blight (Phytophthora infestus) that caused the Irish Potato Famine. Phytophthoras, Greek for “plant destroyers,” certainly live up to the name. More than a hundred species of these fungus-like organisms have been scientifically described, and they generally proliferate in the same way. Once introduced to a location, they can spread undetected in the soil or in water and wreak havoc on crops, nursery stock, and natural ecosystems. Also called “water molds,” they produce free-swimming spores and are more closely related to plants than to fungi. Typically, they rot plant roots or form lesions on leaves that then wilt and lose the ability to photosynthesize.

The particular strain that the SFPUC found — Phytophthora tentaculata — was already on a federal watch list due to the damage it has caused in Europe and China. A study of P. tentaculata on oregano plants in Italy found 80 percent of infected plants died within a month of showing symptoms. In 2010, the U.S. Department of Agriculture listed P. tentaculata in an ominous report on phytophthoras as a strain that would “likely cause severe economic impacts to the nursery trade, as well as environmental impacts on native species” if it ever reached U.S. soil. And here it was, one potted toyon plant away from being set loose in Alameda County.

The SFPUC toyon shipment isn’t the first time P. tentaculata has reared its head in the U.S. There was a case at a plant nursery in Monterey County in 2012. But this second discovery proved that the incident in Monterey wasn’t isolated, and because both cases involved nursery-raised plants headed for restoration sites, it became apparent to the Bay Area’s restoration community that it had a problem on its hands.

A big problem. The SFPUC had taken considerable precautions against introducing phytophthoras and other plant pathogens into its significant land holdings in the East Bay and on the Peninsula. The agency has a “pest and pathogen free” specification in its contracts that requires a number of safeguards to prevent spread of pests and diseases, including inspection of heavy equipment before it enters restoration sites, rejection of seed mixes that contain weeds, and 24-plus-hour treatment of root wads in high-temperature ovens to kill pests and pathogens. “Despite all this, we got infected,” says Greg Lyman, a habitat mitigation engineer for the SFPUC. “Our concern is that we’ve introduced a pathogen into the watershed that could decimate a whole ecosystem, and these watersheds are native habitats to endangered species.”

Just as disconcerting was the possibility that native plant nurseries, many of them small-scale, mom-and-pop operations with the best of intentions, could be unwittingly cultivating and spreading these deadly pathogens. “As it turns out, a lot of them are following practices that are pretty sketchy when it comes to producing clean plants,” says Ted Swiecki, a plant pathologist and consultant to the SFPUC and other public agencies, who examined the sick toyon plants. “There are a lot of things they’re trying to do to reduce their carbon footprint, like reuse pots. It’s like sharing needles. You immediately introduce pathogens into your operation.”

Swiecki, the founder of Vacaville-based consulting firm Phytosphere Research, has observed the spread of a fair number of nasty Phytophthora species. Since his graduate school days in the 1980s, plant pathologists have known that ornamental nurseries were “loaded with these pathogens, but there wasn’t really anything anyone would do about it,” he observes. In commercial agriculture, the main management strategy is to develop Phytophthora-resistant cultivars.

Then, in 2000, researchers identified P. ramorum, a previously unknown Phytophthora species, as the cause of the puzzling plague of dying oak and tanoak trees in Marin and Santa Cruz counties. Despite emergency federal funding, task forces, “death summits,” and quarantines on California host plants, P. ramorum has continued to advance across the landscape to kill more than a million trees in Central and Northern California, and has popped up in other parts of the country as well. As part of the concerted decade-long campaign against P. ramorum, California nurseries have been encouraged to overhaul their practices and carefully inspect plant carriers of the disease. Nurseries have repeatedly been found to unwittingly nurture the pathogen in their plant stocks.

But just as we’re beginning to understand how P. ramorum got here and how it spreads, other destructive Phytophthora species are popping up, sometimes in lethal combinations. In 2009, Swiecki co-published a paper outlining the spread of P. cinnamomi, a species long known to affect nurseries and orchards, into native plant habitats where it’s so persistent in the soil that eradication is not an option, and efforts focus simply on stopping its spread.

Swiecki worries that the proliferation of new Phytophthora species could create a lethal brew in California soils. “You can end up with a mix of Phytophthora species. There are ones that do well in wetter habitat, ones in drier, ones that go after the woody plants,” Swiecki says. “You mix them around and you end up with a huge number of plants at risk.”

Phytophthora tentaculata’s discovery in the Bay Area jarred the restoration community by exposing a major vulnerability in the supply chain of materials heading into wildlands. Native plant nurseries have quickly, and voluntarily, responded. One of the local leaders in the effort to bring about new standards of operation has been Watershed Nursery, a Richmond-based native plant nursery owned by Diana Benner and Laura Hanson, ecologists by training who collect native plant seeds and grow varieties for individual restoration sites.

“This was the first situation I was aware of where it looked like restoration material was the direct vector,” says Benner. “That’s why it was for me, personally, a massive alarm. We’re all doing what we do because we’re trying to protect the environment. That was distressing.”

While the SFPUC went to work, ultimately deciding to raze 9,000 plants (none of those planted tested positive for P. tentaculata, although some presented another Phytophthora, P. cactorum), heat-treat the soil, and switch to relying on seeds for some of its restoration rather than nursery plants, Benner and Hanson quickly got their own house in order. Watershed Nursery was unconnected to the SFPUC incident, but Benner and Hanson began tightening their own protocols with the help of two plant pathologists experienced in best management practices for Phytophthora: Kathy Kosta at the California Department of Food and Agriculture and Karen Suslow, the manager of Dominican University’s National Ornamentals Research Site. According to Suslow, Watershed Nursery has become a pioneer in adapting best management practices to prevent the introduction and spread of Phytophthora in moderate-size native plant nurseries.

“Watershed has set the stage for a number of native plant nurseries. It has caused a groundswell,” says Suslow.

Meanwhile, plant pathologists are trying to understand how the new phytophthoras got here and spread. Nurseries are likely the primary vector, but there are so many other ways phytophthoras can proliferate once they’re here. The restoration and native nursery communities are working hard to ensure they are no longer aiding the spread, but more public education is needed, because all it takes is a boot and loose soil to keep these pathogens moving.

[callout center]Online Extra: Read more about Watershed Nursery’s new approach to eradicating Phytophthora from nurseries. “It’s like when you’re coming into the country, everything needs to wait here,” says Watershed’s Diana Benner.[/callout]