For the time being, you need a stout pair of hiking boots and lots of water–and permission from the East Bay Regional Park District–to explore Irish Canyon, one of the newly acquired properties adjoining the district’s Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve. A capable truck and a guide with the key to many gates will do the job, too. The stream course, lined with oaks and patrolled by an astonishing number of red-tailed hawks, leads you up into the grassy hills east of Clayton, past the dark brush fields of imposing Kreiger Peak. A climb for another day. At an old stock pond, red-legged frogs watch from the safety of the center of the pool.

A piece of new parkland, and a lovely one. But Irish Canyon is emblematic of much more than that.

Something big is happening in eastern Contra Costa County. It is not quite a secret–many people and groups and government types are in the know–but word has reached the general public mostly in the form of isolated bulletins: The East Bay Regional Park District picked up 221 acres along Vasco Road, and another piece near Kirker Pass. . . . A former military base, the Concord Naval Weapons Station, will yield a substantial park. . . . Save Mount Diablo has optioned a property on Marsh Creek. . . . The Contra Costa Water District, making up for the land drowned by a reservoir, buys habitat near the Altamont Pass. . . .

The news, hidden in plain sight, is the way preserves old and new are now linking up to form something much grander: a national park-size block of public lands, centered on Mount Diablo but extending north to Suisun Bay and south at least to the Altamont, and perhaps beyond.

There are now approximately 100,000 acres of publicly owned lands in the northern Diablo Range. At least 24,000 acres more are in the sights of the land buyers, and those acres are very special, chosen to fill in critical gaps. Already, Irish Canyon and other recent acquisitions have fused Mount Diablo State Park and Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve into one open-space expanse, separated only by one road. The park district is within two purchases of bridging a second gap, the one between Black Diamond and the hilly portion of the Concord Naval Weapons Station, also destined for parkdom.

- Long Ridge, Mount Diablo State Park. Photo by Stephen Joseph, stephenjosephphoto.com.

A New Way to Preserve

This surge toward unification is occurring under the flag of something called the East Contra Costa County HCP/NCCP. The first acronym stands for Habitat Conservation Plan, a federal effort blessed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; the second, for Natural Community Conservation Plan, a state matter supervised by the Department of Fish and Game. The present plan, administered by the new East Contra Costa County Habitat Conservancy, is a triumph of what can seem a troubling idea.

Under the federal and state Endangered Species Acts, development that invades the habitats of imperiled species must pay a kind of penance, helping to buy and protect similar habitat somewhere else. At the conclusion of each such transaction there is less habitat overall than there was before–as critics point out–but more of it is secure. If some degraded habitats are rehabilitated in the process, the result can be, if not quite a win-win, at least a win-and-a-half.

The promise of this technique, however, has not always been fulfilled. Since the federal Endangered Species Act first required developers to do mitigation, we’ve discovered that doing such projects one development at a time is inefficient. For the builders, it is a hassle, with expectations sometimes quite unclear. For species and their protectors, the results have also been disappointing. The areas set aside are often of low value and tend to be neglected after purchase, lacking the management sometimes required to keep habitat viable for targeted plants and animals.

Federal HCPs and state NCCPs are attempts to do the job more efficiently–more protection bang per developer buck. By agreement with regulators, developers building in accordance with local plans meet their obligations under the endangered species acts by paying predetermined fees, and the fees go into building and managing preserve systems that are preplanned in detail.

Flagship in the East

- View toward Suisun Bay from Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve. Photo by Deborah Maufer, pixandpieces.com.

The East Contra Costa plan, in the works since 1998 and blessed by both levels of government, is a flagship of its kind. It foresees the development of between 9,000 and 12,000 acres, as called for in local plans. The fees generated will purchase between 24,000 and 34,000 new acres of open space lands.

The essence of the HCP (and catnip to geography fans) is a detailed map showing how the new preserves will help fuse existing ones into an impressive, united mass. When the job is done, a spine of protected land will run down the Los Medanos Hills from Highway 4 to Black Diamond and Mount Diablo. From Diablo, two corridors run southeast to the block of watershed land around Los Vaqueros Reservoir. Between these corridors, the upper valley of Marsh Creek remains rural private farmland. South of Los Vaqueros, the purchase area narrows again, following the main ridge of the inner coast ranges to the county line, just north of the Altamont Pass. The more development occurs in the areas zoned for it, the more fees will flow and the more land will be added to flesh out this open-space skeleton.

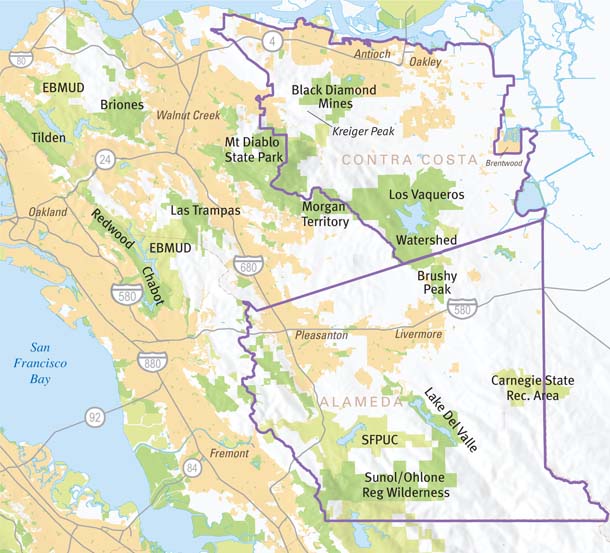

- The purple lines show the areas covered by the East Contra Costa County Habitat Conservation Plan (top) and the Eastern Alameda County Conservation Strategy (bottom). Map by Bay Nature, from base data by GreenInfo Network.

The plan is a test case for the principles, delineated not too long ago, of conservation biology. Going back to early studies of extinctions on islands, this discipline teaches that in general, large preserves help species more than small ones, linked preserves better than separated ones, and broad preserves better than skinny ones. Corridors linking low elevations with high and southern areas with northern are given high priority. In a world of climate change and other impacts, such large-scale habitats give species and ecosystems their best chance to adjust.

In previous decades, agencies bought land for scenic quality and for recreation, with habitat preservation as a by-product. Today’s effort starts with habitat; it is scenery and recreation that come along for the ride.

A striking thing about this HCP is how much grassland it targets for acquisition. This is partly because the higher forested or brushy hills have already been purchased; it also shows a keen new appreciation of what grassland is and does. Insects, reptiles, and small mammals that live in grass nourish the rest of the food chain. “Grasslands are the bread bowl for all the other species that are now endangered. Rangeland is finally getting its due,” says Bob Doyle, who recently stepped up from acquisitions chief to manager of the park district. Says John Kopchik, executive director of the East Contra Costa County Habitat Conservancy, “We resisted the temptation to avoid controversy by keeping the preserve system high in the hills.”

Quick Out of the Gate

Since its 2008 inception, the East Contra Costa HCP has sprinted ahead. In its first two years, it funded the preservation of some 8,500 acres, about a quarter of its maximum target. “The pace of acquisition is phenomenal,” Kopchik says.

In an era of shrinking budgets and state park shutdowns, this achievement seems marvelous. It was just as the program got going that the economy crumpled, drying up development and the fees developers were to pay in support. Fortunately, the HCP had eggs in other baskets. The Fish and Wildlife Service had already committed $21 million in grants–dependent on a local match. That match was available because the voters of the East Bay Regional Park District had passed Measure WW, extending the district’s property tax. In addition, grants from the state Coastal Conservancy and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation played a part, and Pacific Gas and Electric and the California Department of Transportation kicked in some money to mitigate for disruptive work on power lines and roads.

The engine has been “jump-started,” as Bob Doyle puts it. Will it keep running when the federal money runs out and funding depends largely on development fees? Will fees provide, as planned, the funds for managing newly protected habitat? Those questions remain unanswered, and so, says Lech Naumovich, director of the Golden Hour Restoration Institute, the scheme “hasn’t been ground-truthed yet.”

Still, the park district brings more to the table than funds. It has long-honed expertise in land acquisition. And it is able to offer long-term habitat management, a key link missing in many such efforts. Though the conservancy is the essential intermediary, the end result of the HCP effort will be a huge expansion of the East Bay regional parks.

Another key player is the nonprofit organization Save Mount Diablo (SMD). Long before officialdom embraced the idea of a unified greenbelt in eastern Contra Costa, SMD was trumpeting the idea. “We help set the vision–a bigger vision than the agencies can,” says the organization’s Seth Adams. Steeped in local knowledge won parcel by parcel, SMD plays an advisory and public advocacy role and also, on occasion, brings in a crucial acquisition on its own. Its purchase, 15 years ago, of the Chaparral Spring property on Marsh Creek Road was the first small step toward the Diablo-Black Diamond linkage that the HCP and the park district have now completed at Irish Canyon and Kreiger Peak.

Looking South

_HiRes_SHarrington.jpg)

- Brushy Peak Regional Preserve, on the border of Contra Costa and Alameda counties, might someday serve as a hinge between a growing network of preserved lands in Contra Costa and several potential open space properties across the Livermore Valley south to Ohlone Regional Wilderness. Photo by Sarah Harrington, harringtonphotos.com.

It is a brisk 40-minute hike from the end of Laughlin Road on the outskirts of Livermore, up a swale marked with the characteristic whitish crust of alkaline soils, past another of those bucolic stock ponds that turn out to be key habitat for endangered red-legged frogs. As you climb, you realize how the name Brushy Peak misleads: This 1,700-foot summit is woodland, a dark island of oaks in a world of pale grass. At your back the view unwinds until, near the top, you turn around and see the whole panoply of the ridges south of the Livermore Valley–the southern, and larger, part of the Diablo Range.

Brushy Peak Regional Preserve is a hinge point. Though in Alameda County, it effectively forms the southern anchor of the nascent Contra Costa greenbelt. And for people with a certain kind of vision, it forms the northern anchor of a second arc of green: a potential zone of protection crossing the Altamont Pass, riding the divide some miles south, and joining at Lake Del Valle with the transverse band of parks and San Francisco watershed lands extending west to Sunol. The vision can stretch on over the horizon: south from Sunol to the hills around Mount Hamilton near San Jose, and on to enormous Henry W. Coe State Park east of Morgan Hill. Along the way, various other nuclei of lands owned by public agencies or the Nature Conservancy form particles around which a larger network of protected lands could precipitate.

But the distances between are bigger than in Contra Costa County, and nothing quite like the Contra Costa HCP is going on down here. Because the threat of development is less, federal agencies have not made this stretch a priority. For historical reasons, the East Bay Regional Park District also can’t spend Measure WW money here. And there are fewer landowners in these hills who want to sell, either for development or for preservation. Rather, they want to stay in business. To the district’s Bob Doyle, these facts suggest another approach, one playing out over a longer period of time and based on the acquisition of conservation easements, which limit development while allowing ranchers to remain as owners, and stewards, of the land.

.jpg)

- Hikers on a guided walk in Irish Canyon, which, like much of the land purchased through habitat conservation plans here, is not yet open to the public. Photo by Scott Hein, heinphoto.com.

A couple of ongoing planning efforts could help the work along. One is called the Eastern Alameda Conservation Strategy. Like the Contra Costa HCP, it seeks to give a structure to the mitigation that developers, or public agencies with infrastructure projects, must do. It reviews the landscape area by area and species by species, yielding a list of types of terrain that might be purchased for mitigation, such as creekside corridors, alkali wetlands and meadows, and serpentine rock types home to rare and specially adapted species. The effect is less a clear map and more a bridal registry: a list to be consulted at need, from which future developers can pick and choose.

A second effort that could play into building the southern arc is called the Altamont Wind Resource Area HCP. This more narrowly focused plan, still taking form, seeks to reduce the killing of raptors by wind turbines and to offset the losses that still take place with measures like buying habitat. Some money for the acquisition of lands or easements may result.

A third significant player is placing bricks in emerging habitat structures both north and south of the Altamont Pass: the Contra Costa County Water District. In return for drowning 600 acres of land under an expanded Los Vaqueros Reservoir, the water district has agreed to buy some 7,000 acres of mitigation land in Contra Costa but also in Alameda and San Joaquin counties. One very significant district acquisition straddles Interstate 580, the humming artery that separates northern and southern reaches of the Diablo Range.

I-580 was never designed with wildlife passage in mind. Nevertheless, the laws of engineering and the needs of adjacent property owners created a few connections: massive culverts and a couple of broad underpasses for livestock. The water district recently purchased parcels on either side of the freeway, with the associated rights of passage through a cattle-way. It’s a step toward a major goal of Save Mount Diablo’s Seth Adams: “making sure that Mount Diablo never gets cut off from the Diablo Range to the south.”

What is emerging in the eastern hills of the East Bay counties is a peer to the great open space systems of the counties west of the Bay. In Marin County, substantial work was done by the federal government, with creation in succession of Muir Woods National Monument, Point Reyes National Seashore, and the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. In the Santa Cruz Mountains of San Mateo and Santa Clara counties, private philanthropy has been a very important driver, through such groups as the Peninsula Open Space Trust and Sempervirens Fund.

In the inner coast ranges of Contra Costa and Alameda counties, Seth Adams proudly notes, it has been more of a bootstrap effort. Through the East Bay Regional Park District, the people have repeatedly voted to tax themselves for open space, thereby creating an institution that can do its work in good times and bad.

With the East Contra Costa Habitat Conservation Plan and the parallel efforts to the south, big dreams are coming into reach. “We’re compressing the distance between vision and reality,” says Bob Doyle. Adams puts it in grander terms: “We are reassembling the Diablo wilderness.”

.jpg)