an Shive grew up in central New Jersey working as an assistant to his photographer father — meaning, he says, “I didn’t want anything to do with photography.” But after leaving the East Coast for college in Montana, Shive picked up the camera, and found that he loved the power it gave him to explain this new place to people back home. “Immediately, I was using it as a tool to communicate,” he says. After leaving college, he moved to Southern California and landed a job in Hollywood, where he spent a decade marketing films and television. He went to screenings with movie stars. He watched Danny Elfman compose a film score. He worked on Spiderman. And one day, he says, he looked at the slate of upcoming movies and realized he just couldn’t do it anymore. At the time he’d been taking long weekends in parks around the Western United States, photographing landscapes and selling his images to magazines like National Geographic and Time. So when he couldn’t do Hollywood anymore, he started his own photo company, Tandem Stills + Motion.

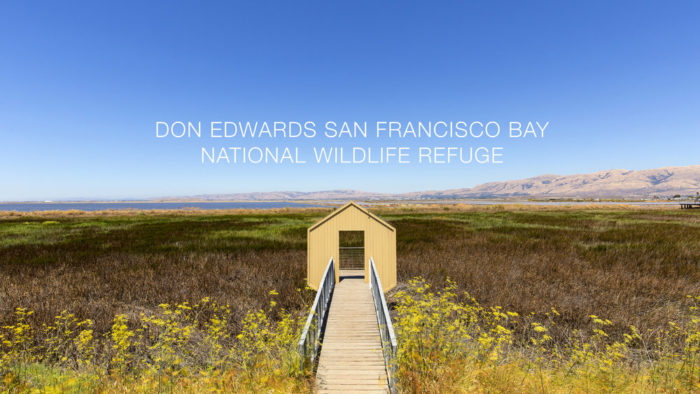

Shive has now spent the last decade traveling the world as a conservation photographer, with a particular focus on the National Parks. Tandem’s latest film series, which was released on Oct. 17, showcases the country’s 14 urban national wildlife refuges, including Don Edwards San Francisco Bay. Shive sat down with me earlier this summer to talk about nature photography, the challenges of filming around the Bay, and how the Bay Area’s refuge compares to the rest of the world.

Eric Simons: As a visitor with an assignment to think about the Bay and this refuge cinematically, what are you looking for?

Ian Shive: You’re looking for those exceptional moments that can resonate and get people motivated to want to find what it is that you’re showing. Honestly, this is quite a beautiful place to sell. Great light, you’ve got the Bay and water. Technically you’re a little weather dependent. You’re always hoping for certain conditions and textures.

I’m an extraordinarily technical person, but you’re trying to bring the technical into the philosophical. How can dramatic lighting and a lens flare convey the emotional component of what it’s like to walk down this bridge and feel the wind blow by? I’ll look for that.

Yesterday, we saw a couple of people walking, and the light was shimmering in the background and you could see the wind blowing through their hair as they were walking, and I’m like, “That’s the perfect moment.” I couldn’t tell you if that’s what I wanted prior to it happening, but when you see it and you’re well-positioned for it, you know it’s there. It’s that ability to try and time it right and then get lucky.

ES: It’s an interesting challenge shooting urban refuges. How do you balance looking at it from a landscape perspective and looking at it from a perspective of what the people are doing who are moving through it?

IS: With the urban refuge, my approach is don’t go into something and try and make it something it’s not. I don’t crop out the highway, I don’t crop out the bridge, I don’t try not to show people. I don’t go in and say I’m going to make this look like Yellowstone. Instead, I come in and say I’m going to make this look like what about it is the best of it. That’s what I’m here to do. I’m here to show people what the best is that they can find.

I think it’s important to make people a part of it. I think people are an important part of the environment, whether it’s a national park or refuge or wilderness area with very few people. People are part of our planet. I’d say one of the most defining characteristics of my career as a photographer was, very early on, instead of doing just landscapes and national parks, I started to include people and the human element. People relate most to people. You don’t relate to a polar bear if you’ve never seen a polar bear, but you relate to that moment standing there as the sun sets.

ES: Do you come into an assignment like this with a shot list in your head?

IS: Yes.

ES: What’s your list for the refuge?

IS: Recreation, biking, running, fishing. Water. Showing water up against the marshland. Low-water, rising water, traffic on highways, urban communities, SFO airport, and then other things like that.

It’s like any film process. You’ve got to start wide and work your way in. I tried to figure out what are my establishing shots. The salt flats, seeing it from the air, getting a sense of it in context. You’re thinking of the story, of course. Story is what drives it. It’s not just pretty shots, it’s a story. You’re trying to think, “Am I telling the whole story and am I doing it well? Am I capturing the tech component, and am I capturing the Bay component, the sprawl, the openness, the wildlife, the people, the visitor experience?”

I do also come in with the idea that I’m going to be open to what I encounter, which is an important part of the process.

ES: If you were to give advice to somebody who was hiking out here in the refuge, and they want to capture their experience here beyond just standing there and clicking, what can an amateur photographer look at or how might you counsel an amateur to see this place better?

IS: Don’t shoot at eye level. Get low, get high. We all see the world at eye level, so anything that you show that’s not at eye level, immediately it’s different. It feels a little fresher and it will capture people’s attention easier.

That’s the quick, easy thing that people can take away. As far as how to see better, I think we tend to have tunnel vision. Something I learned really early on that I think was instrumental in my approach to photography is that you don’t realize it when you are walking down the path, but you tend to pick a spot and look at it. If you stop and try and take all of it in, you start to get that landscape idea. I tell people to take all of it in. Keep your mind open, keep your eyes open. It sounds simple, but you’d be amazed.

ES: You mentioned that view of the people walking. Anything else that stands out about the refuge from a landscape perspective, or from an interaction perspective?

IS: It’s really flat. It’s tricky. I think the big challenge of this refuge is how spread out it is and what it takes to move around the Bay. I think that’s frustrating a little bit. I’m probably the only person who is trying to go to all of the refuge every day. Getting high up is definitely key to understanding this issue and this place.

The Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge film was released by Tandem Stills + Motion and the US Fish and Wildlife Service on Oct. 17, 2016. You can see other films in the series and view Ian Shive’s other conservation work at Tandem.film.

.jpg)

-300x154.jpg)

.jpg)