Nobody wants to be called a bottom-feeder. It’s a shame the word became a term of opprobrium; many respectable creatures make their living that way. Gray whales hoover up seafloor sediments to get at buried prey. So do the bat rays (Mylobatis californica) that gather in the shallow warm waters of coastal California bays and sloughs every spring to feed, mate, and give birth.

These are the flat-bodied shark relatives that allow themselves to be petted in a tank at Monterey Bay Aquarium. Most visitors don’t realize that the friendly fish are true stingrays. The stinging spine and its venom evolved for defense against sharks, sea lions, and other predators. UCLA marine biologist Laura Jordan was once zapped in the wrist by a young bat ray. “The pain comes in waves,” she says, and lasts “a good 20 minutes.”

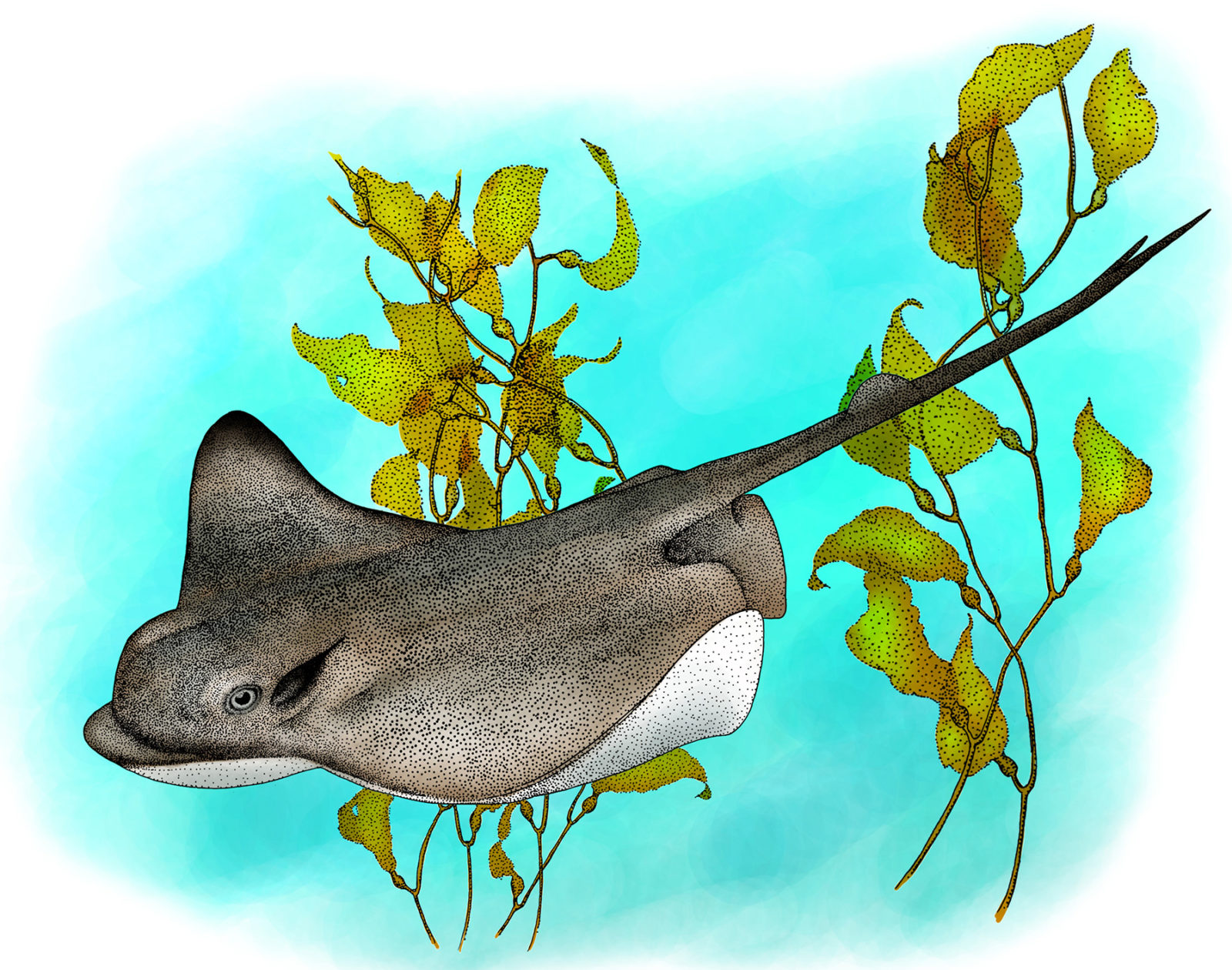

Despite that experience and the resulting scar, Jordan remains fond of these odd creatures: “Bat rays are one of the cutest species. They’re appealing because they have a little bit more of a face than the others.” Fish biologist Milton Love, author of Probably More Than You Want to Know About the Fishes of the Pacific Coast, calls them “unbearably endearing creatures.”

Jordan studied bat rays and other stingray species to learn how they cope with an obstacle imposed by their anatomy: With their mouths on their undersides, they can’t see what they’re hunting or eating. She found that they compensate with a unique dual sensory system. All fish, from lampreys to trout, have a lateral line, an array of pores that registers changes in water pressure. In rays, the line has become a network covering both the upper and lower sides and extending out onto the “wings”– expanded pectoral fins. It’s used to detect pulses of water expelled by buried clams and other mollusks. A parallel electrosensory system picks up the weak electric fields generated by prey. Bay rays, Jordan says, have a higher density of sensory pores than the other species she’s worked with and excel at hitting their targets.

Diet varies by location and season. The rays have been called opportunistic generalists. Jim Hobbs of UC Davis, who monitors fish populations in and around South Bay salt ponds that have been reconnected with the Bay, has found clams, grass shrimp, and the exotic yellowfin goby in their stomachs. In Elkhorn Slough, rays feast on fat innkeeper worms. Humboldt Bay rays eat a variety of clams, worms, shrimp, and crabs, graduating to larger prey as they mature.

Ray predation was once considered a major threat to commercial oyster beds. Growers killed thousands every year in Humboldt Bay alone. “That’s not a problem anymore,” says John Finger, whose Hog Island Oyster Farm raises the tasty bivalves in Tomales Bay. “The cultivation technique changed a long time ago. Everything is in floating plastic mesh bags the rays can’t get into.” Ironically, larger Humboldt Bay rays are major predators of red rock crabs, which do prey on oysters.

A hungry ray leaves its mark on the seafloor. “The holes they dig are very steep-sided,” Finger explains. “Stepping into one is like walking off a cliff. During summer you have to watch your step in the mudflats.” According to Jordan, the rays use a kind of hydraulic mining: “They suck in water through their spiracles [modified gill slits] and blow it out through the mouth, while using their wings to get some leverage and clear out the sand they’re moving.” Once it finds a clam or crab, a bat ray crunches it with its plate-like teeth, sorts out the edible bits with its tongue, and spits out the hard residue.

The rays that congregate in Tomales Bay and other estuaries, some gathering year after year, are not just after food. This is where females deliver the pups that were conceived nine months to a year earlier. Large mature females with three- to four-foot wingspans may have litters of 10 or 12. The pups are born tail-first, with their wings wrapped around themselves and their sting in a sheath. They linger in the birthing grounds until fall. Meanwhile, the adult males, which can grow to be two feet across, will have joined the females to sire the next generation.