Along Tesla Avenue at the south edge of Livermore, rows of grapevines angle from the roadside, showing a trace of fall color on their taut wires. Almost within earshot of the bustle of town, it’s the kind of place you’d expect to see For Sale signs. Instead at many gates you read this notice: “This land preserved in perpetuity by the owner and Tri-Valley Conservancy.”

Livermore was once California’s premier wine region. At the end of World War I, there were 50 wineries in the southern arc of this valley, with about 5,000 acres in grapes. Then came Prohibition, the Depression, another war. The wine district shrank and didn’t rebound. What boomed in the valley was housing. Year after year the suburban front moved southward.

Third-generation vintner Jim Concannon, taking care of business at one of the two major surviving wineries, did not find it a good omen when a new boulevard nearby was named Concannon Avenue. “We thought they named it after our family because they wanted to put it right through our vineyard,” he says. Pressures mounted; the possibility of selling out and relocating the business to lower-cost Salinas or Monterey beckoned. But somehow the Concannons stayed put, and so did their neighbors the Wentes, whose operation was, and is still, the valley’s largest.

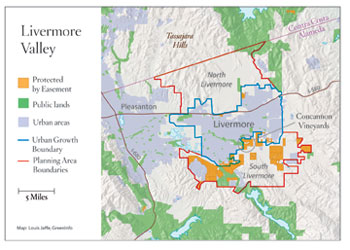

All around the Concannons, development skirmishes swirled. Sentiment in the City of Livermore turned toward preseravation; Alameda County, the key planning authority, wasn’t so sure. Matters came to a head in a courtroom in 1991. Directed by a judge to work out their differences, the two governments spent a year devising a new joint program for South Livermore. Its essence was to declare a firm, final limit to urban growth, and to construct, along that line, a rampart of flourishing agriculture, locked in place through conservation easements.

With no major funding in sight, the plan set up a kind of bootstrap operation in which the development of land just north of the future boundary would pay for the preservation of farmland just south of it. Builders of housing near the edge of town had to purchase easements in the farm zone at the rate of one acre per unit developed (and an additional acre per acre developed). Fees collected from developers also paid for the founding of a South Livermore Land Trust (now the Tri-Valley Conservancy) to receive and administer these easements.

A second route to protection was also set up. Rural landowners in the planning area are permitted to split properties down to 20-acre parcels—smaller than the prevailing zoning—provided that 18 acres of each 20 are planted with vines or orchards and likewise placed under easement.

The original South Livermore Valley Area Plan had two targets: to put 5,000 strategically located acres under easement, and to foster the creation of 24 new small wineries. The wineries goal has already been met, and the acreage goal is within sight: 3,800 acres of easements are held by the land trust. More important, those holdings are on the verge of forming a continuous bastion along the urban-rural boundary.

Intensively managed vineyard lands are not to be confused with nature preserves, but the wine belt serves to protect natural areas both within and outside its limits. Easement lands adjoin and buffer several large parks. As a condition of easement, creek banks must be revegetated if necessary and in no case farmed. Simply by halting sprawl, too, the program gives a measure of protection to open lands far south of its formal limits, down into the wild interstices of the Diablo Range.

How the pieces fit can be seen along Arroyo Mocho, a big tributary of Alameda Creek that crosses the Concannon property (and which over the aeons laid down the vineyard’s valuable rocky soil). As a child, Jim Concannon played on the arroyo’s banks and caught turtles in its pools. Formerly intermittent, the stream now serves as part of a regional water supply system and flows all year round, “which brings tremendous wildlife,” he says. “We’ve got cranes, we have mallards, we’ve got fish in the creek.” The Zone 7 Water Agency, on whose board Concannon sits, envisions a public trail all along the stream; one stretch already exists, through the winery and into the city’s Robertson Park downstream.

In the spring of 2005 the conservancy expanded its zone of operations to include all of Alameda County east of the bayside rank of hills. How it will get traction outside South Livermore remains to be seen, as the mandated financing that worked there does not apply more widely, and the agency’s independent budget is small.

- Louis Jaffe, GreenInfo Network

Its next theater may lie on the north side of the Livermore Valley, where the grass-covered, rolling Tassajara Hills are in the hands of speculators and developers with plans at the ready. Livermore voters have just declined to give their blessing to a greenbelt-busting proposal from Pardee Homes, but the vote provides only a respite. Vintners and open space advocates alike hope to repeat the South Livermore model here in North Livermore. Again they envision a band of high-value agricultural land, under easement, creating a tangible urban edge. Under one possible plan, developers, in return for permission to build more units in town, would fund the conservancy’s purchase of easements in the Tassajara Hills.

The Livermore Valley model is exciting wider interest, partly because it is largely self-financing, not dependent on grants or taxes. The fast-growing City of Brentwood in Contra Costa County, for instance, is looking it over with an eye toward starting something similar.

“We have a chance to save this valley,” Jim Concannon says. He’s speaking of South Livermore, but people in many another “valley” can take note.

.jpg)