Eucalyptus trees on Albany Hill are wasting away from blight. Some people may cheer—but these trees are also home to endangered monarchs.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter and understand everything better!

Eucalyptus trees on Albany Hill are wasting away from blight. Some people may cheer—but these trees are also home to endangered monarchs.

A naturalist on the “flowers of winter”

Do mushrooms require a certain kind of substrate?

What are some the biological consequences of climate change in Northern California?

They’re one of the most sought-after edible mushrooms in the world. At least 10 species live in the Bay Area.

A mycologist’s perspective on the spread of a deadly poisonous mushroom across the United States.

They’re long and stringy and they hang from trees in the fog zone …

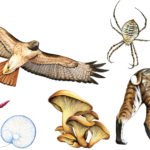

Illustrator Jane Kim and the California Center for Natural History share six species to watch for this fall.

Plants make all other life on Earth possible. But most animals don’t eat dead plants — so how do the nutrients plants create get into the environment when the plant dies?

In which California is the first state to have a state lichen.