“When a whale washes up it’s kind of like being a doctor on call,” says Moe Flannery, senior collections manager at the California Academy of Sciences. Flannery’s day job means caring for more than 140,000 bird and mammal specimens at the Academy, but she is also a first responder when marine mammals wash ashore. At 5:45 a.m. on a Tuesday last summer, I piled into a truck with Flannery on a response call. The stranded animal was a “small” 20-foot humpback calf that washed ashore on Wildcat Beach in Point Reyes National Seashore.

By the time Flannery and a team of researchers from the Academy of Sciences, The Marine Mammal Center, and the National Marine Fisheries Service arrived around 8 a.m., the scene was calm. Wide gray skies stretched as far as the eye could see, a slight breeze rippled throughout the beach, seagulls croaked to themselves. This was the first whale I’ve ever seen dead or alive, and although it was young and relatively small, I was overcome with its grandeur. And then of course, there was the smell. Nothing could prepare me for the stench. Flannery says she thinks it smells of the ocean, but to me it smelled more like rotting pad Thai and durian fruit.

Flannery and the team set to work immediately. They sawed through blubber and dug deep into Pepto-Bismol-colored whale slime in search of bones and tissue samples. The dissection is necessary: from the outside, many stranded marine mammals appear to have died naturally, but necropsies often reveal a different story.

“Generally you can’t tell much from the outside, you really have to open it up to see,” Flannery says. “There’s so much information to be gained by each carcass and I really feel strongly that if we have the opportunity, if we can get the team together, and if it’s in a place we can access it, we need to gather as much data as possible to try to determine how that animal died.”

(The California Academy of Sciences is part of a 120-member nationwide group called the Marine Mammal Stranding Network. The organizations in this network are authorized through National Marine Fisheries Service permits to respond to strandings; it’s otherwise illegal to even touch a dead marine mammal.)

The network has been busy lately. Gray whales are experiencing what scientists have labeled an “unusual mortality event” on the West Coast of North and Central America, while humpback whales are experiencing an unusual mortality event on the East Coast. Scientists like Flannery want to understand the lives and deaths of these whales to eventually piece together what’s happening to our oceans. “I guess that’s what drives me to drop everything even when I have three reports due,” she says.

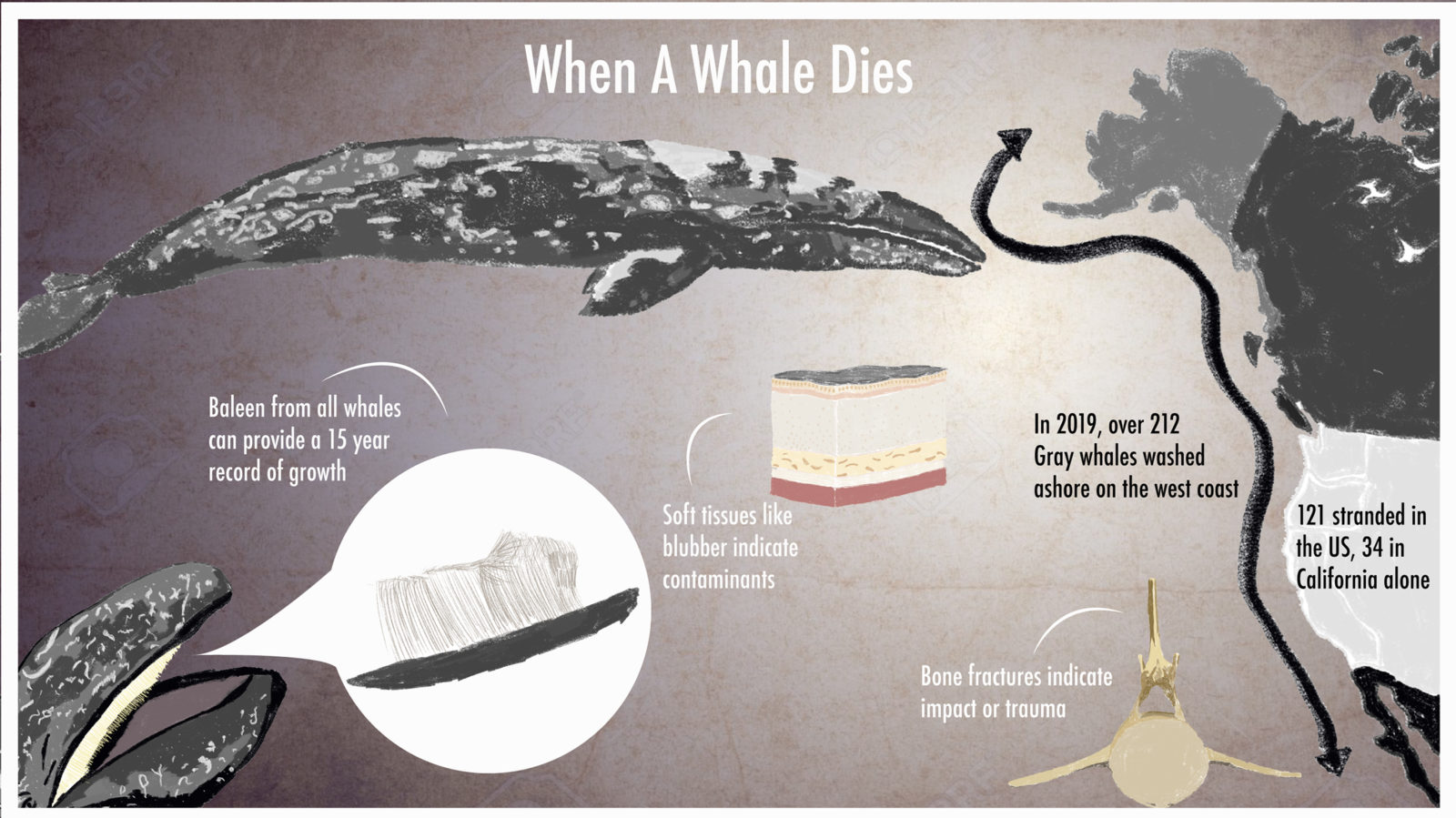

In the last year Flannery has dropped everything many times, particularly over the gray whale. In 2019, more than 210 gray whales washed ashore on the West Coast, including 121 in the United States and 34 in California alone. Last May, NOAA announced an investigation into the high number of deaths reported on the West Coast to try to determine a cause. The “unusual mortality event” designation is one of more than 60 such events declared since 1991.

That’s one way tracking and analyzing strandings matters. “If we hadn’t been monitoring strandings in the past, we wouldn’t necessarily know we’re seeing a lot more gray whales than typical,” says Jessie Huggins, stranding coordinator from Cascadia Research, a Washington-based science nonprofit. “Having past necropsies comparing them to current necropsies, you can see the difference between this year versus the last 10 years.”

Gray whales have one of the longest migrations of any mammal on Earth, completing a 10,000 mile round trip from their calving grounds in the warm waters of Mexico to the cold and productive feeding areas of the Bering and Chukchi Seas in the Arctic. The whales only feed while in these Arctic waters, feasting on small benthic invertebrates called amphipods, to build fat stores to last them throughout their journey. If they don’t pack enough blubber while in Alaska, they won’t have enough energy to complete their migration down south and back again. And a lack of food seems to be the case with the majority of stranded whales examined. Most of the dead animals are emaciated, with very little body fat. Bill Keener, a research associate with The Marine Mammal Center’s Cetacean Field Research Program, said he’s seen gray whales coming into the San Francisco Bay in 2019 and now again in 2020, many of them appearing skinny, a sign of malnutrition.

Researchers have two main theories on why the animals are starving. One is that the gray whale population has reached its carrying capacity — essentially that there are too many whales and too few amphipods for the entire population to get its share during last summer’s feeding frenzy. After nearing extinction from industrialized whaling in the early 1900s, the gray whale population has bounced back to pre-whaling levels thanks to government protections. NOAA estimated that there were 26,960 gray whales in the Eastern Pacific in 2018, and the creatures were successfully removed from the Endangered Species List in 1994.

Researchers also suspect warming trends in the Arctic could be exacerbating problems with the whales’ food. Reduced sea ice might be affecting the food resources available for the whales. In summer 2019 the Bering Sea averaged 9 degrees warmer than average. Amphipods live on the sea floor and are fertilized by algae associated with the sea ice. As the ice melts away, the amphipods do too. Whales in turn might be moving towards other food sources like krill, which do not contain the amounts of fatty lipids they need to build sufficient blubber energy reserves.

Still, the reason for the gray whale die-off remains inconclusive. “There’s a whole gamut of things that could occur when we have things come to shore,” says Justin Viezbicke, the California Stranding Coordinator for NOAA. “Most of these animals are nearshore costal species and so when they do come ashore they’re providing this opportunity to learn what’s happening out there.”

Which brings us back to the stranded humpback. Humpbacks, too, have changed their food sources and behavior in the last few years, seemingly in response to changes in the ocean. Warmer water has meant shift to more concentrated feeding inshore, and more feeding on anchovies. Flannery and the team wanted to see if this stranded young what fit into a pattern they’ve seen before.

As part of a necropsy, the Academy collects hard samples like bones and baleen. Bone fractures indicate impact or trauma, while a tooth cut in half reveals the animal’s age. Back in the lab, scientists drill deeper into each layer for traces of stable isotopes that show what the animal ate. Baleen from all whales that have it can provide a 15-year record of growth: hormones indicate when the animal bred, when females were pregnant, and when they gave birth. Ear plugs, although rarely recoverable during a necropsy, are rich with insights thanks to the presence of stable isotopes, hormones, and contaminants. Soft tissues, like blubber, also contain contaminants and are collected by The Marine Mammal Center to better understand pollution during the animal’s lifetime.

“I learn something from every single case,” says Barbie Halaska, a researcher at The Marine Mammal Center. “I can then pass it on to other veterinary students or pathologists.”

After analyzing of the the 20-foot humpback I saw in the field this past summer, scientists found blunt force trauma on its skull. Flannery, Halaska, and their respective teams observed broken skull fragments stained with pink blood, which showed the animal was alive when its skull fractured. The skull was actually found on the beach several feet outside the whale’s body, which was mostly intact.

A probable (but not verifiable) cause might have been a ship strike. A similar fracture could also have happened in a feeding frenzy, if a much larger whale came down hard on the young humpback.

The skull stayed on the beach after everyone was done with the examination. “We don’t often take skulls,” Flannery says. “They’re just too big and we don’t have space in our collections. We’ll take pelvic bones to archive as a record, but other bones are too big.”

The Marine Mammal Center’s necropsy team took frozen samples of the whale for their hospital’s archives and research projects. Many scientists from around the world use samples for projects in conjunction with permits from NOAA. Halaska’s team took samples of baleen for an outside researcher to run isotope analysis to find what the animal was feeding on that year and previous years. They are still awaiting the results. The team didn’t take further diagnostic tests or histology because the animal was in good body condition and her primary cause of death was trauma consistent with a vessel strike.

Experts at the Marine Mammal Center have witnessed humpback whales entering the San Francisco Bay in greater numbers every year since they were first sighted feeding there in 2016. Humpbacks mainly forage on krill as a main food source. In recent years, warming water temperatures associated with climate change have lead to an increase in krill movement off the United States West Coast, and so humpback whales end up migrating to new areas in search of food. “More broadly, climate change affects water temperatures and prey availability, leading to shifting food sources for marine mammal populations and other marine species,” Halaska says.

A necropsy is like pressing rewind on the camera. From lying dead stranded on the beach the whale reanimates, turns into a creature we know ate krill, swam in possibly new waters near the Point Reyes Coast looking for new food sources, and faced the consequences of manmade dangers like ships. With enough poking and prodding, we can develop a snapshot of how these magnificent animals died, but also how they lived.