TULARE LAKE, CA—Beyond a ‘road closed’ sign, telephone poles file out into flood water, stretching all the way to the hazy coastal range in the distance. Occasional houses, farming equipment and barns emerge from the choppy blue expanse like a mirage.

And everywhere you look, birds: Ibises bob between rows of drowned wheat in nearby flooded farm fields. Cliff swallows swoop back and forth where water laps against asphalt, gathering mud for their nests. Black-necked stilts, tri-colored blackbirds, egrets, western sandpipers, curlews, long-billed dowitchers, and more have found plentiful habitat in the southern Central Valley this year—including the resurrected Tulare Lake, which surged back to life with this winter’s historic rains.

“There will be hundreds or maybe even thousands of birds in those fields, foraging and looking for insects and other tasty morsels,” says Xerónimo Castañeda, conservation manager for California Audubon’s working lands program.

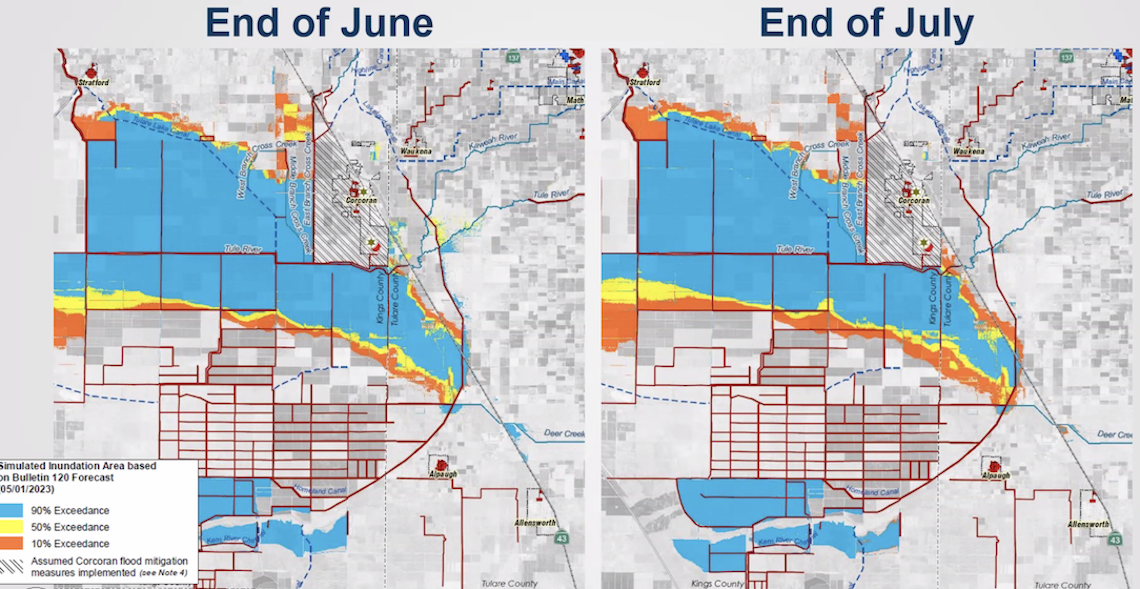

Last week, Tulare Lake—which straddles Tulare and Kings counties—reached its forecasted peak size at 182 square miles, about the same surface area as Lake Tahoe, though a tiny fraction of its depth. The lake has wreaked havoc: Homes and farmland were submerged. Nearby towns scrambled to raise levees. Tens of thousands of cows were evacuated.

Tulare Lake could continue to grow through mid-July, but not enough to endanger surrounding towns, state modeling shows. Soon, the lake will gradually begin to shrink. Nearby towns are still recovering from flood damage and grappling with remaining floodwater. In the meantime, the lake and thousands of acres of nearby flooded farmland are providing a temporary respite for the millions of migratory birds that pass through California along the Pacific Flyway every year.

“Lands that otherwise wouldn't have been flooded are now providing a habitat, filtering water and providing all the other environmental benefits that come with a wetland,” says Jake Messerli, chief operating officer for the California Waterfowl Association, a bird and wetland conservation and hunting nonprofit.

Recharge basins and standing water on farm fields are hosting flocks as well, providing ample nesting and resting habitat––and a unique opportunity for bird watching. Miguel Jimenez, who manages the Kern National Wildlife Refuge Complex, encourages visitors to come see the birds while the water is plentiful.

“Just on the drive to and from work, there were literally thousands of shorebirds out there utilizing those floodwaters,” says Jimenez.

A ghost lake returns

Over 150 years ago, Tulare Lake blanketed over 700 square miles of the southern Central Valley, from what is now I-5 to about halfway to the Sierra Nevada. In wet years, snowmelt swelled the lake to over 1,000 square miles––four times the area of Lake Tahoe. But as the four rivers that fed it were dammed for farm irrigation, the mighty lake dried up.

With this winter’s parade of atmospheric rivers, however, Tulare Lake is back. The water rests on a layer of dense clay, which keeps it from percolating down into underground aquifers. Tulare is also a closed basin, so the water cannot flow to the ocean. In 1983, the last time Tulare Lake returned on this scale, Tulare Lake lingered for almost two years until it eventually evaporated.

This year, some floodwater was diverted to wetlands in the Kern National Wildlife Refuge, about four miles south of Tulare Lake. This alleviated flooding on nearby farms while providing more habitat for birds. It’s the first time in the past drought-stricken decade that the refuge has received its full water allocation. Now, the refuge has become home to a nesting colony of white-faced ibises, as well as nesting waterfowl such as mallards, cinnamon teals, American coots and northern shovelers.

Other wildlife refuges are also benefiting. This year, California Waterfowl took on excess water from the local irrigation district for Goose Lake, the organization’s 2,200-acre wetland preserve about 12 miles south of Tulare Lake. Messerli and colleagues are using the water to encourage wetland plants that feed local birds, including swamp timothy, watergrass, and swamp milkweed. These wetland plants also provide food and habitat for invertebrates that birds can eat, and plenty of habitat for breeding.

“Our resident birds will nest there and raise their young,” says Messerli, referring to the species that breed in California, rather than migrating north to Canada and Alaska. “We’re seeing a lot more ducklings than we've seen in the past.”

Now birds can socially distance

The water could also help in other ways. An uncountable number of birds, both wild and domestic, have died in the ongoing avian influenza pandemic. Waterfowl are the main carriers. But with so much water on the landscape, birds have room, effectively, to socially distance—which could reduce the risk of transmitting the flu virus, compared to their cramped quarters during drought years.

“The floods were probably one of the best things that have happened in regards to avian flu,” says Matt Kaminski, regional biologist for Ducks Unlimited, a national waterfowl habitat conservation and hunting nonprofit. According to Kaminski, detections of avian flu in the Central Valley rose in December 2022, but began to decline as the rains came and birds dispersed across the flooded landscape. Kaminski hopes that this year’s wet winter will show how valuable managed wetlands are—they help manage floods, recharge groundwater, and provide wildlife habitat for birds.

But risks lurk in the floodwater, too. After the 1983 floods, avian botulism killed or sickened more than 28,000 birds in and around the Kern Refuge. Clostridium botulinum, the bacterium that produces the botulism toxin, naturally occurs in soil and thrives in warm, shallow water. The bacteria can spread via aquatic invertebrates eaten by birds, causing paralysis and often death if ingested.

Jimenez and other wildlife managers are anticipating an avian botulism outbreak this summer. Because the Kern refuge is near Tulare Lake, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife is preparing it to serve as a “duck hospital” and monitoring center, to track and rehabilitate infected birds.

Despite these risks, refuge managers believe the floodwaters are an overall positive for birds living in the southern Central Valley and migrating along the Pacific Flyway, especially if the water lingers for a year or more.

“When these natural flood events happen, by default they get the water that they need. It gives their population a little boost,” says Messerli. “They'll benefit from this, so long as things remain wet.”