Shorebirds are funny-looking things. With those long skinny legs and long skinny necks and bills, sometimes they can look like something out of a cartoon. But the life of a shorebird is often far from funny. Those long skinny necks and long skinny bills and legs are important tools for a shorebird’s day-to-day survival.

You can get a good idea of what a bird eats based on its type of bill. For example, a short, fat bill, like on a parrot, is usually used to create great pressure and crush seeds or nuts. A bill with a hook at the tip, like on a pelican or a hawk, snags things—a slippery fish or a squirrelly rodent. So what about those shorebirds? The majority of shorebirds have a long skinny bill, and that bill is often used for probing.

There are lots of things to probe on a shoreline: like holey rocks, and in-between rocks, and driftwood, and into the sand, and burrows in the sand and mud. Most shorebirds are invertebrate predators, adapted to eating things like crabs, bivalves, and worms. They also curb the populations of lesser-known invertebrates like amphipods, isopods, and grasshoppers.

But not all shorebirds (order Charadriiformes) look alike. Plovers, for example, have the typical long legs, but their neck and bill are short and stubby by shorebird standards. Instead of probing the substrate, a plover prefers to stand and wait for movement on the mudflat surface. Then it dashes over and seizes the prey. Plovers’ eyesight is highly developed; their large eyes enable them to see well at night, as we’ll discuss.

The beautiful American avocet, while it does look more like your typical shorebird, has one peculiarity: its long, very thin bill has a turned-up, or convex, curve. Kind of like a smile. One would think they use this bill to probe into mud and burrows, but that’s not the plan exactly. The turned-up end of this bird’s bill has tiny, lamellae-like structures along the inner margins, which help it trap food. Avocets prefer to eat free-swimming inverts by picking and probing in the water column, but when that’s not working, they can also turn their bill into a straight muckraker. They drop their bill down onto the mud surface, in a parallel manner, and start to swing it from side to side, like using a scythe to cut hay. While performing this mud-slinging act, its bill is slightly open, and any unfortunate, mud-dwelling inverts that are caught are promptly dispatched. It’s funny how such a beautiful bird as the avocet can have some very messy table manners.

Shorebirds are highly dependent on the tide. When the tide is out, the beach and mudflats are exposed, and it’s time to eat. When the tide is in, for a shorebird it’s time to take a break, shut down, and wait until the next low tide. So time of day is not as important as time of the tide. For a shorebird, if the low tide is at 3 a.m. then dinner can be at 3 a.m. At night you might see marbled godwits, black-bellied plovers, and semipalmated plovers, and sometimes, other species prone to night foraging will turn up, especially willets, dunlins, and dowitchers. This is the life of a shorebird.

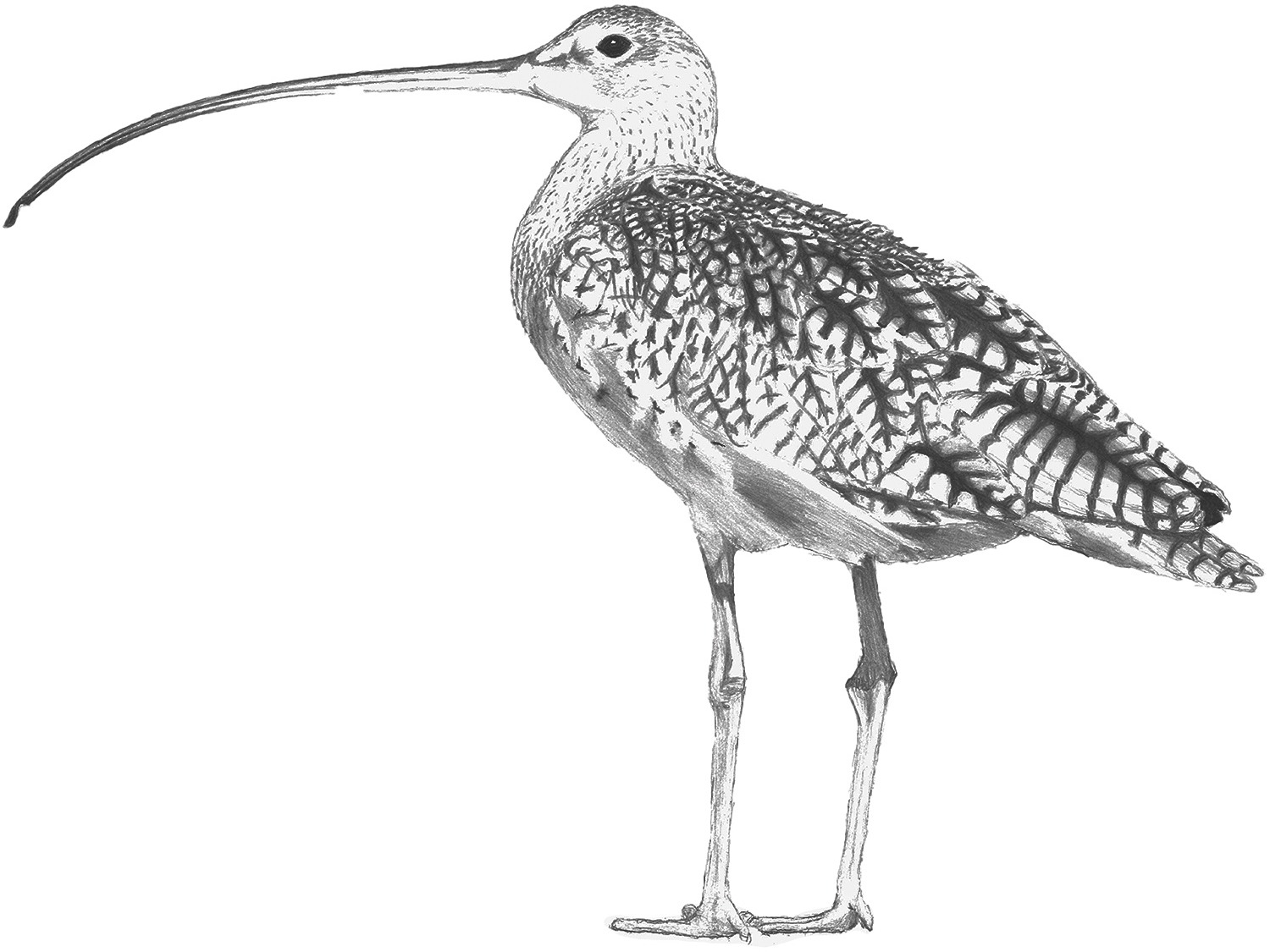

Their lives can be very complex. The long-billed curlew, as the name implies, is another of those long-billed and -necked shorebirds, actually bordering on “elegant” to my eye. Its bill is specifically designed to probe deep curved burrows, for things like ghost shrimp and lugworms. But this bird has a secret. While you can see the curlew along our San Francisco Bay shoreline during the winter months, when spring hits it disappears, flying to states like Idaho, Oregon, Utah, and Montana to breed in the high altitude, grassy plateaus of these areas!?

Why would a bird so perfectly designed for the shore choose to breed in such an un-shoreline-like environment? There is no single, clear answer, but part of it may be because there are so many insects (grasshoppers, beetles, caterpillars, etc.) to be had during the summer months, for so little energy expended. Those long bills and legs work perfectly for walking through tall grass and picking off big, fat, juicy insects before they even know what hit them. For a recently migrated, brooding female who needs plenty of protein for herself and a male needing to feed fledgling chicks, these are irreplaceable grasslands.

The San Francisco Bay is a major stopover along the Pacific Flyway migratory route. And right now (November through March) in the East Bay, the San Leandro Bay and Arrowhead Marsh are drawing thousands of overwintering shorebirds and a chance to see those long-necked, long-legged, and funny-looking shorebirds for yourself.