After a winter of historic rains, California’s reservoirs are filled to the brim. Rivers are supercharged—and have flooded much of the Central Valley. With the water came a deluge of news voicing worries that California is letting all that water wash into the sea after years of drought—and heralding the idea of capturing it to recharge our long-parched groundwater aquifers. The political will is strong: Gov. Gavin Newsom has issued three separate executive orders aimed at amping up recharge efforts.

But while recharge is a useful way to put surface water back underground, experts say it is a limited solution.

When It Rains

California groundwater recharge by the numbers

What’s an acre-foot, you ask? Picture water spread out over one acre, one foot deep.

DWR recharge funding: $68 million for 42 projects in 2021 and 2022

Average groundwater overdraft in the San Joaquin Valley over 1988-2017: 1.8 million acre-feet

Groundwater deficit accumulated in the valley in 2021 and 2022 alone: 14 million acre-feet

Estimated “managed” groundwater recharge in California so far in 2023: 3.8 million acre-feet

Floodwater diverted for recharge this year: 92,410 acre-feet

“We have unrealistic expectations of groundwater recharge, as a way of addressing groundwater overdraft and long-term drought in particular,” says Jay Lund, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Davis. “We will probably be able to reduce the overdraft by maybe 15 to 25 percent by increased groundwater recharge. It’s nice, but it’s not going to be enough.”

To solve California’s groundwater woes, we will need to increase the water supply, as recharge does. But we must also reduce demand—namely, by pumping less groundwater. California’s Department of Water Resources has tracked 2.1 million acre-feet of recharge so far in 2023, about one-third of last year’s groundwater overdraft of 6.5 million acre-feet. To make a meaningful dent in that overdraft, agencies and landowners will need to take irrigated agricultural land out of production.

“We, along with the locals, are doing everything we can to maximize recharge,” says Steven Springhorn, an engineering geologist at the California Department of Water Resources. “But we know that that’s not the only action that’s needed to get to sustainability.”

An underground drought

Chances are, groundwater is flowing beneath your feet.

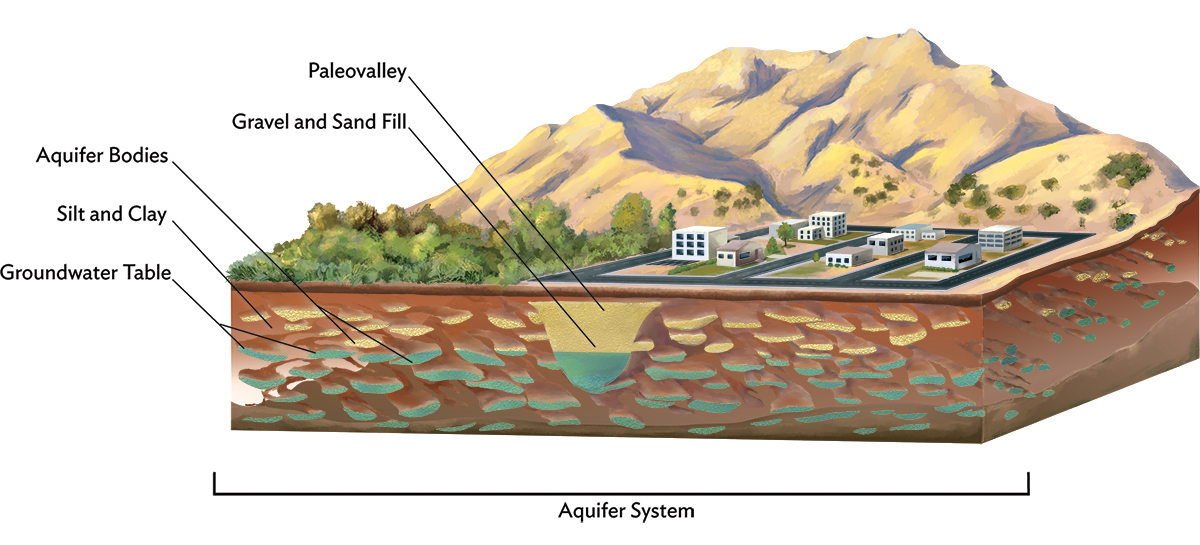

Groundwater basins are made up of layers of underground aquifers, which store water between layers of rock, gravel and sand. California’s aquifers have the capacity to store 850 million acre-feet—17 times more water than all of the state’s major reservoirs combined.

Some surface water naturally percolates down and replenishes these aquifers, but it does so rather slowly. When people talk about recharging groundwater, they usually mean “managed aquifer recharge,” where humans intervene to accelerate the percolation process. This can involve injecting water back down into aquifers through wells, flooding agricultural fields, or building recharge ponds to hold water while it percolates.

“The conditions this year really led to a lot of activity and a lot of excitement about the opportunity to recharge,” says Andrew Ayres, a research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California’s water policy center. “There are really high hopes, especially in places like [the] San Joaquin [Valley].”

Farmers in California’s most profitable agricultural regions hope recharge will help them avoid costly reductions in how much water they pump. But the San Joaquin Valley also sits atop the most overdrafted aquifers in the state, with about 1.8 million acre-feet more water pumped out each year than is replenished. Groundwater sustainability plans in the region ambitiously proposed that 75 percent of the overdraft could be made up for with recharge—but many of the local groundwater sustainability agencies aimed to recharge the same water, according to Ayres. He says it’s more likely that 75 percent of the overdraft will be resolved by reductions in pumping, and that maybe 25 percent can be made up with recharge.

This unusually wet winter has relieved California’s surface water drought, but not the state’s groundwater deficit, which has developed over decades. California uses 1 million to 3 million more acre-feet per year than is replenished—mostly due to overpumping. About 40 percent of California’s freshwater supply for human use comes from groundwater—and it’s more like 60 percent in drought years. Climate change is exacerbating the whiplash between drought and flood years. This makes it even more essential to recharge groundwater during wet years to rely on in dry years.

“If the groundwater is being depleted, there’s only two ways to reverse that: you either reduce pumping, or you increase recharge, or both,” says Graham Fogg, professor emeritus of hydrogeology at UC Davis. “In this age of California trying to get its groundwater basins in balance, the more popular alternative is recharge. But in truth, people have to do both.”

The power of recharge

Experts agree recharge is worthwhile. It can replenish dry wells and groundwater-dependent ecosystems, counter seawater intrusion along coastlines, and keep land from sinking, a major problem in severely overdrafted areas.

Among the best opportunities for recharge are underground geological features known as paleo valleys, which a 2022 Bay Nature feature covered in depth. These long-buried gravel-and-silt riverbeds, reaching up to 100 feet deep and a mile across, make for excellent groundwater storage. Yet most of California’s paleo valleys have yet to be discovered; state-funded surveys are mapping them in the Central Valley.

Once a paleo valley is found, storing water in it can still pose scientific, legal, and financial challenges. One paleo valley identified by Fogg and colleagues in Sacramento County seemed perfect—except that it was underneath private property, which would mean extensive negotiations and paperwork. Recharging a significant amount of groundwater, whether in paleo valleys or elsewhere, will likely require paying thousands of landowners to flood their fields or build recharge ponds.

In regions with aquifers that are not so overdrafted, recharge projects have boosted groundwater levels after this year’s rains—but that underground bounty is far from equal across the state. Out of the 3,400 California wells monitored by the Department of Water Resources, 59 percent of them showed no change in water levels after this year’s wet winter, and 6 percent actually dropped.

“It’s a year like this where we’re learning a lot about how much recharge can really get done,” says Ayres.