Roaring winds engulfed the southern San Joaquin Valley in nearly mile-high plumes of dust, five days before Christmas in 1977. Severe drought had parched the region for years, and gusts reaching an estimated 192 miles per hour tore across the farmland. Highway traffic came to a halt; paint was sandblasted off trapped vehicles. The dust was so thick that it blocked out the sun.

The storm raged on, spanning three days. Dust crept into homes through every nook and cranny. When residents finally emerged, they found that livestock had been buried alive, along with creeks and irrigation canals. Over the next several months, hundreds of people came down with valley fever, a disease caused by inhaling the airborne spores of the dirt-dwelling fungus Coccidioides immitis, commonly called cocci. The event became known as the Great Bakersfield Dust Storm, and it resulted in at least five deaths and $40 million in damages ($200 million today), not including subsequently ruined agriculture.

The threat of destructive dust storms looms again as the Central Valley reckons with drought, new limits on groundwater use, and wells running dry from decades of unsustainable pumping. To stem the groundwater system’s collapse, California passed the historic Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) in 2014, which requires balanced groundwater use in the coming decades. For the first time in the state’s history, farmers can’t extract more water from aquifers than is replenished. As a result, groundwater users face having to take swaths of their land out of production to comply with irrigation limits. In the San Joaquin Valley, over half a million acres—10 percent of that valley’s irrigated farmland—will need to go dry by 2040, according to estimates from the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC), an independent research institution.

The PPIC also investigated whether taking land out of agricultural production—known as fallowing—under SGMA might “turn the San Joaquin Valley into a dust bowl,” according to the study’s author. It found that about 75 percent of the valley’s rural communities at high risk from dust-prone soils will need to fallow land. Yet there is no overarching plan for what to do with all the unirrigated fields; the fate of each acre will be determined by the farmer who owns it. Researchers fear the valley could become a chaotic patchwork of cultivated fields and barren land that harbors weeds, pests, and dust in a region that sees some of the worst air quality in the nation.

“No one wants a California dust bowl,” says Ann Hayden, associate vice president of the Environmental Defense Fund’s climate resilient water systems program.

As SGMA deadlines loom, groundwater sustainability agencies, environmental organizations, and farmers in the San Joaquin Valley are scrambling to prepare for a drier future by experimenting with ways to repurpose fallow farmland. A restoration project in Tulare County is the first to convert farmland into wildlife habitat under SGMA. If the project succeeds, it could serve as a model for some of the 500,000 acres that need to come out of agriculture to comply with SGMA’s irrigation limits—if local farmers can be convinced that fallowing their land for conservation is worthwhile.

“[Farmers] are going to be really influential in determining how and whether SGMA gets implemented,” says Andrew Ayres, a research fellow at the PPIC and author on the dust study. “If you can make it a win for them, you can get to sustainable groundwater management.”

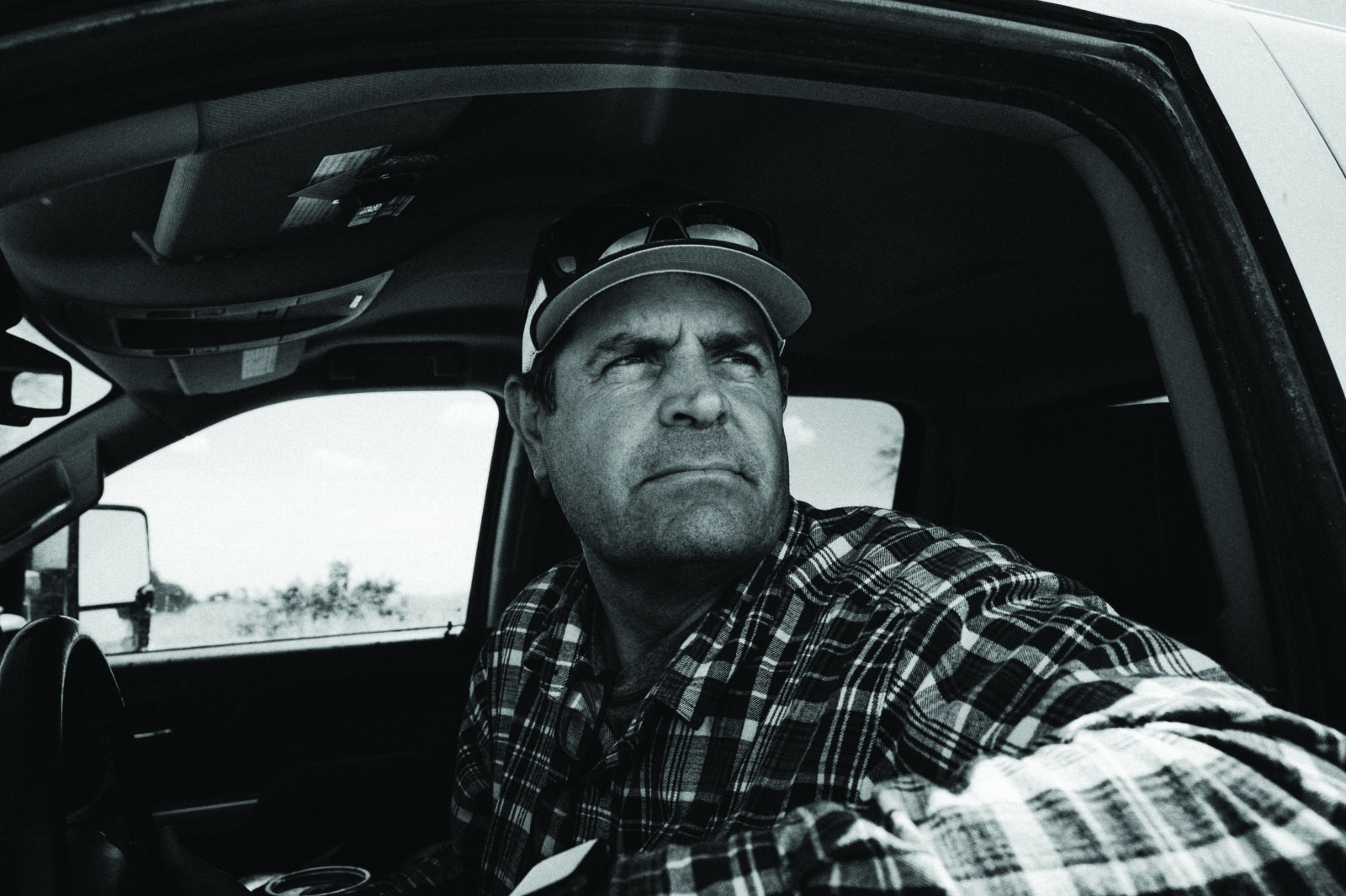

Frank Fernandes, a third-generation dairy farmer, bumps along a pitted dirt road in his white pickup truck and stops at the edge of a pond on his family farm. Fernandes and his two younger brothers run a 3,000-cow dairy with 1,500 acres of forage crops in Tulare County, in the southern San Joaquin Valley. The county sits about halfway between the Bay Area and Los Angeles, and it’s home to more cows than people. About one third of the dairy farmers in the region sell their milk to Land O’Lakes for butter and cheese.

“I’m deeply passionate about protecting the environment—I live here,” says Fernandes. “I just want to be able to continue doing what I’m passionate about: farming.”

Nearby, a burrowing owl stands motionless—like a tiny speckled statue—at the edge of the pond. After this winter’s relentless rains, Fernandes’ ponds, which span 20 acres, are full. One teems with birds—American avocets peck and bob in the mud, and egrets land with a splash. Cows moo across the way. Aspen, Fernandes’ six-month-old Great Pyrenees puppy, romps along the muddy shore while her owner checks a water meter and looks out over the pond.

“I got my own little Pixley Lake here,” Fernandes jokes.

But it’s not a lake. The bird-friendly ponds are recharge basins, full of water that will percolate into and replenish the aquifers below. The local Pixley groundwater sustainability agency (GSA) incentivizes farmers like Fernandes to use such basins on their private land. In return, Fernandes accumulates future credits to pump groundwater.

“I’ve taken out 20 percent of my acreage in different ways,” says Fernandes. Besides the two recharge basins, his farm uses its fallow acres for solar panel arrays and a methane digester. The solar arrays send electricity into the local grid in exchange for power credits, and Fernandes sells the methane for biofuel.

Where Fernandes lives, the Lower Tule and Pixley GSAs will need to take 15,000 to 20,000 acres out of irrigation to achieve sustainability. Farmers in the area can choose to purchase more water than their share for $90 to $280 per acre-foot. These funds then offset overpumped groundwater. For example, the money may pay for more surface water, recharge infrastructure, or temporary fallowing and cover crop programs. The cover crops use minimal water and hold down the soil, preventing dust.

Despite these successful programs, in March 2023 the Tule subbasin’s sustainability plan was deemed inadequate by the California Department of Water Resources. If a GSA’s plan is not approved, the State Water Resources Control Board can intervene by monitoring well pumping, imposing fines, and issuing cease and desist orders until an adequate plan is agreed upon.

Now, the Lower Tule GSA is experimenting with another opportunity to permanently fallow land—this time for restoration of San Joaquin grassland habitat.

About four miles away from Fernandes’ farm is Tulare County’s Pixley National Wildlife Refuge. The nearly 7,000-acre refuge preserves San Joaquin grassland, a habitat that also survives in Carrizo Plain National Monument, and a few other refuges scattered throughout the Valley. Here, kangaroo rats hop through the dry scrub, dragging their long tails behind powerful haunches and oversize feet. The rodents stuff their cheeks full of seeds that they will bury in small caches outside labyrinthine burrows. Their prolific tunneling creates shelter for endangered blunt-nosed lizards. When the rats can’t escape into their tunnels, they become food for raptors and endangered San Joaquin kit foxes.

“San Joaquin desert upland habitats were largely converted in the Central Valley,” says Scott Butterfield, a biologist for The Nature Conservancy who specializes in San Joaquin grassland. “Between 90 and 99 percent of that habitat has been lost over the past 150 years.”

Sharing a north and west property line with the Pixley National Wildlife Refuge is a 500-acre field known as Capinero Creek. Until a few years ago, it was one of the region’s more than 350 dairy farms. Now, the site is stubbly with a shorn wheat cover crop, which holds down the soil and keeps the land in good condition for what comes next. In five years, Capinero will hopefully be planted with native saltbush, bladderpod, and other native plants, supporting more kangaroo rats, kit foxes, and other San Joaquin grassland species.

Despite its agricultural appearance, Capinero Creek is in the vanguard of conservation. It is the first farmland taken out of production in the San Joaquin Valley that will be restored to wildlife habitat to conserve groundwater under SGMA.

“You want to clean up groundwater? Put some natural habitat back in the area,” says Fernandes, the Tulare farmer and president of the brand-new Tule Basin Land & Water Conservation Trust, which now owns Capinero Creek.

Fernandes believes that for agriculture in the valley to continue, farmers need to participate in land repurposing to conserve groundwater. He is determined to figure out how to make farming in Tulare sustainable while contending with severe drought and SGMA regulations.

The Nature Conservancy is co-managing Capinero’s restoration along with the Tule Trust. The conservancy aims to restore 20,000 to 50,000 acres of the valley into habitat over the next 20 to 25 years. “We try to find these win-wins, right? A win for both people and nature,” says Butterfield. “It’s really this demonstration of how we can contribute to a sustainable groundwater future, and hopefully contribute to the largest recovery of threatened and endangered species in the history of California.”

Reaching that goal will require farmers to collaborate with environmentalists. But after decades of animosity between them, projects like Capinero Creek will remain notable exceptions without incentives for farmers to permanently fallow their land.

Regardless of land fallowing disputes, the San Joaquin Valley is in a water crisis.

Eighty percent of water used in California goes toward agriculture, and in the San Joaquin Valley that number climbed to 87 percent between 1988 and 2017. The valley’s agricultural wonderland of abundant fruits, nuts, and vegetables relies on pumping more groundwater than the region’s aquifers can replenish. Every year, nearly two million more acre-feet of water are being pumped out of the valley’s aquifers than are being replaced. (An acre-foot is enough water to cover one acre, or roughly the area of a football field, one foot deep). This unsustainable situation became painfully apparent in the last few years of severe drought.

“There’s often a mischaracterization that SGMA is to blame for the water scarcity situation we have in the valley,” says Hayden. But “if not for SGMA, we would have much more dire consequences coming to the agricultural sector, because we would have groundwater aquifers overdrafted to the point of no return.”

During the 2012–2016 drought, 2,600 domestic wells were reported dry statewide—about half of them in Tulare County. In the summer of 2022, Tooleville, an unincorporated community in the county, lost its water supply when municipal wells went dry. Nestled between the Sierra foothills and a sea of farmland, the town relied on trucked-in tanks of water for residents to shower and wash dishes and on bottled water for drinking.

Groundwater overpumping also leads to subsidence—a phenomenon where overdrawn aquifers cave in and cause the ground to sink. Some parts of the valley floor have dropped as many as 28 feet since the 1920s, when farmers began to drill wells. Parts of the Tulare lakebed town of Corcoran, about five miles away from Fernandes’ farm, have sunk as much as 11.5 feet since 2007.

“You can drive around the [San Joaquin] valley, and you can see the subsidence that’s occurring, you can see the wells that are going dry,” says Dan Vink, a longtime resident and irrigation consultant in Tulare County. “[SGMA is] either going to be successful, or there’s going to be a tragedy of the commons when it comes to water use in California.”

While complying with SGMA is necessary to save the valley’s aquifers, it isn’t easy to convince farmers to take their land out of production. Land fallowing under SGMA could result in more than $7 billion in farm revenue losses in California each year, according to estimates from a 2020 economic impact report from researchers at UC Berkeley.

“It’s not going to be a costless transition,” says Ayres, the PPIC researcher. “Not just landowners, not just groundwater users, but communities are potentially going to be suffering pretty meaningful economic hardship as a result of this.”

The Berkeley report estimates that each year, an average of 42,000 agricultural jobs will be lost in the San Joaquin Valley, and 85,000 jobs will be lost statewide due to SGMA overall. Tulare was among the top three counties predicted to suffer job losses. The report concluded that the economic impacts of SGMA will be disproportionately felt in the valley’s lowest-income communities.

“So your focus is clean drinking water for [disadvantaged communities],” says Fernandes, referring to SGMA’s aim of restoring clean groundwater for drinking. “But if it means putting farmers out of business to provide that, what is that community going to look like when there’s no jobs?”

While some GSAs, such as Lower Tule and Pixley, have launched Capinero’s restoration and successfully set up incentive programs for recharge and temporary fallowing, many GSAs in the valley are struggling to collaborate with farmers on SGMA at all.

In September 2022, hundreds of farmers gathered for a public groundwater meeting held by the Madera County GSA, about 70 miles north of Tulare, to vote on penalty fees for overpumping. Outraged farmers claimed the proposed fees would put Madera agriculture out of business and threaten their livelihoods. Children held up signs that read “save our farms.” The GSA fees were intended to enforce sustainable groundwater use and fund local recharge projects, repairs for dry wells, and land repurposing programs—similar to the incentives in the Lower Tule and Pixley basins. Eighty farmers blocked these fees with a lawsuit. While the suit makes its way through county courts, the Madera GSA’s groundwater projects remain unfunded.

According to Fernandes, urbanites who blame farmers for wasting water don’t understand the value of California’s food supply. “We grow the safest food anywhere in the world,” he says.

Joey Airoso, a fourth-generation Pixley dairy farmer and another board member of the new Tule Trust that owns and co-manages Capinero Creek, is wary of conservationists’ zeal. “It really sounds good to certain people to put everything back into conservation until people start starving to death … I think there’s a balance,” says Airoso, who farms 100 acres of pistachios and forage crops, and tends 1,800 cows with his son and grandson. “Land fallowing is a tool that’s going to help us protect the best farmland down in the Pixley Irrigation District.”

Fernandes recalls traveling with his family to San Francisco years ago for his son’s brain tumor treatment. When one doctor learned they were farmers, he immediately brought up water use in the Valley.

“He goes, ‘You guys waste a lot of water. We need the water for our environment, and people. We can buy our food cheaper from another country,’” recalls Fernandes. “That’s probably one of the most ludicrous responses I’ve ever heard from somebody so smart … My instinct was to be defensive, but I realized that he just didn’t know. He just didn’t know.”

Fernandes is uneasy about the future of farming in the valley. He got involved with Capinero’s restoration in part because he worries that if farmers like him do nothing, groundwater regulations will push out family operations, leaving only big corporate farms that have the political and monetary backing to “survive SGMA.”

Dan Vink, the irrigation consultant, acknowledges that while there are many corporate ag operations in the valley, the backbone of Tulare is still multi-generational family farms. The distrust of environmentalists and state government in the area is palpable, and the idea of taking land out of production feels preposterous to many farmers. Vink points out that adjusting to new water use standards and being forced to fallow land can be devastating, and he agrees that getting farmers on board can be an uphill battle.

“That’s an emotional struggle for a lot of people,” says Vink. “I’ve had guys sitting in my office, these farmers with cowboy boots and shit on their jeans, literally in tears, because they don’t know if they’re going to be the one that’s going to lose the family farm because of these new regulations.”

Fernandes laments the suspicion and animosity many local farmers feel about repurposing land.

“We have a lot at stake, the farmers on this board,” says Fernandes, referring to the Tule Trust. “We’re staking our reputations on this. We’re the ones that are going to take the slings and arrows from the community if it’s not successful.”

In 2019, Vink arranged the multiagency collaboration that set Capinero’s restoration in motion. His consulting company and The Nature Conservancy helped the Pixley Irrigation District secure a $5 million grant from the Bureau of Reclamation to purchase the land. In 2022, the Pixley Irrigation District received another $10 million from California’s Multibenefit Land Repurposing Program. The program supports projects that reduce groundwater use while also providing environmental and community benefits. The Pixley Irrigation District is the first of the grant recipients in the San Joaquin Valley to put their repurposing plan into action.

Vink has little patience with conservation groups or other outsiders swooping in to try and force change on the valley. He also has little sympathy for farmers dragging their feet and continuing the disastrous groundwater pumping practices of the past. In his view, success for Capinero as a pilot project means making its restoration affordable and scalable.

“The example that we’ve been able to create in the Tule basin has gotten a lot of attention,” says Vink, who often receives calls about the project. “I’m optimistic that something like what we’re doing in the Tule basin is going to replicate itself up and down the valley.”

Fernandes and Scott Butterfield, The Nature Conservancy biologist, look out over Capinero Creek. Squinting into the afternoon sun, they discuss what to do about restoration delays due to this winter’s flooding and the unexpected arrival of nesting tricolored blackbirds, a threatened species in California.

When tricolored blackbird nests are found in farmers’ wheat fields, the area is cordoned off and set aside with no harvesting or disturbances allowed. Butterfield seems concerned by the frenzy of blackbirds swooping in and out of what would have been the first part of Capinero to be prepped for restoration.

“I’m glad they’re here,” says Fernandes, happy to see the blackbirds at Capinero instead of on a farmer’s wheat crop. When asked what is at stake for him and the Tule Trust in Capinero’s success, Fernandes sighs. For him, navigating the contradicting worldviews and assumptions of conservationists and fellow farmers is delicate and exhausting. When a neighbor found out Fernandes himself was planting Capinero’s cover crop, suspicions that he was profiting from environmentalists’ zeal to fallow land led to accusatory phone calls.

“We’re nervous, because we have some of our friends saying, ‘Oh, you’re just siding with the environmentalists, you’re not helping, you’re taking ground out of production,’” says Fernandes. “I’m tired of the phone calls, of speculation. I don’t want to deal with it.”

When asked what is at stake for him and The Nature Conservancy, Butterfield quickly clarifies that the opportunity for conservation groups to restore native grassland on fallow lands should not be compared to what farmers have to lose.

“There’s nothing at stake for me, because I’m not a farmer,” says Butterfield. “Their livelihoods are at stake, their community is at stake, so it’s way more real for them. That’s why it’s inspiring to work with people who are trying to have that forethought of, ‘how can we keep this community farming in a sustainable way?’”

Butterfield ponders how environmental groups can play their role in repurposing fallow land responsibly, in a way that offsets the negative impacts for farmers while still reducing groundwater use under SGMA and creating habitat for wildlife.

“The last thing any of us want to do is be seen as, like Frank [Fernandes] was saying, these liberal environmentalists showing up just to take everything and not think about the impacts,” says Butterfield.

The planting stage of Capinero’s restoration is a long way off, due to native seed shortages and the time needed to grow native shrubs in a nursery. While The Nature Conservancy figures out how to move ahead with those plans, Fernandes and the rest of the Tule Trust will work to get more funding and gather support for the project from their friends and neighbors.

“I don’t know any farmer that hates the environment and wants to destroy it. They don’t,” says Fernandes. “We live here too. We’re part of the ecosystem.”

Thank you to the following generous donors who each gave $250 during our 2023 Local Heroes celebration to help make a feature article in Bay Nature possible: Seth Adams, Catherine Engberg, Robin Grossinger, Blanca Hernández, Maya Hernández, Bill Korbholz, Andrea Mackenzie, Renata Marquez, Perl Perlmutter, Diane Poslosky, Dan Rademacher, Cindy Russell, Ivan Samuels, Susan Shaw, EkOngKar Singh Khalsa, John Steere, Anh Tran, Don Weden.