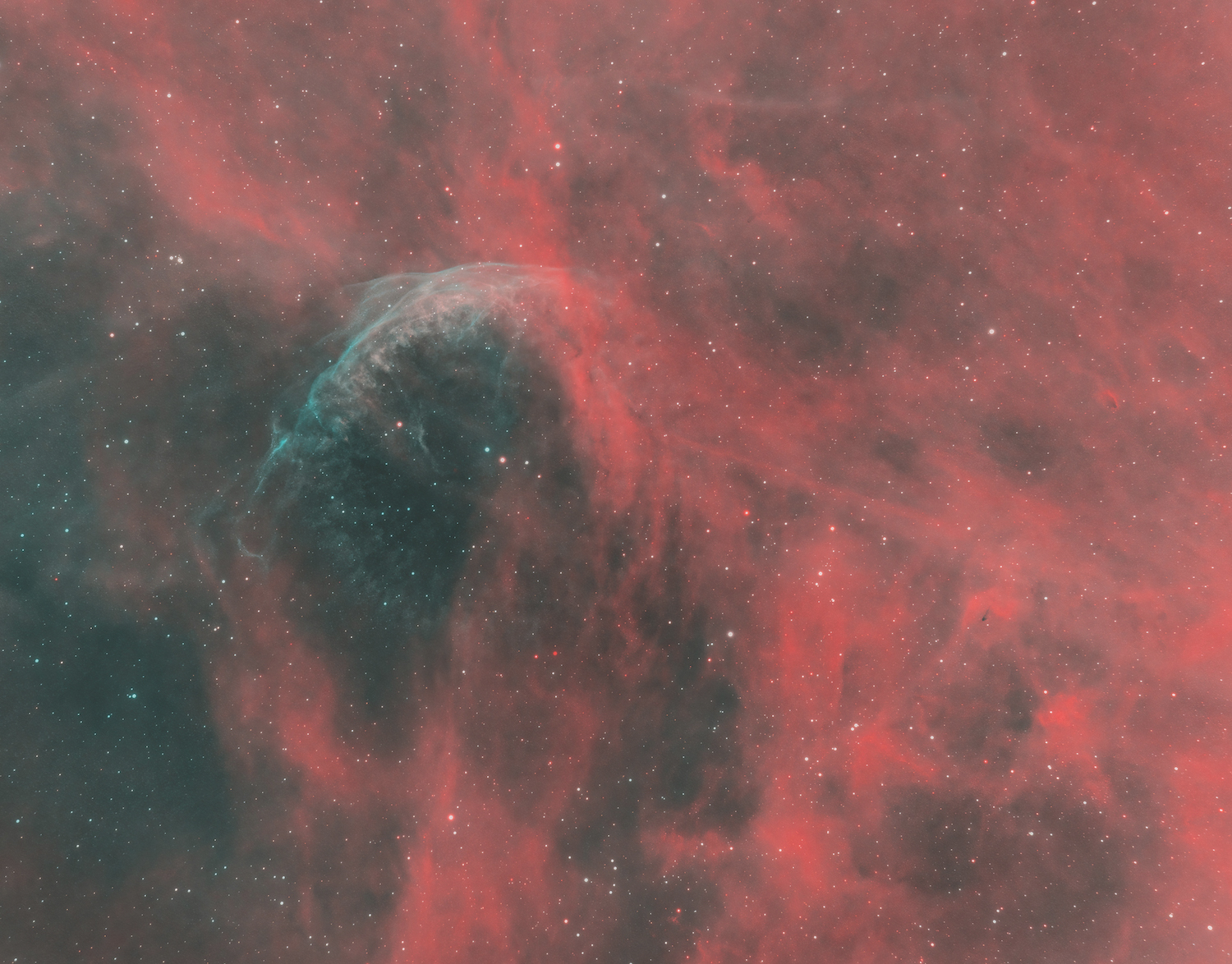

It’s 7 p.m. on a crisp October evening. My telescope is set up in the backyard, aimed at an object more than 6,000 light-years from Earth called WR 134. The abbreviation stands for Wolf-Rayet 134, one among a very strange class of stars that emit massive puffs of gas and dust that often take on strange, otherworldly shapes. To my eye, WR 134 looks a bit like a spinning saw blade or the radiating lines on the shell of a nautilus.

WR 134 is not something you can see with your naked eye. This dim, distant object is best detected through the artificial eye of a digital camera. There is an unparalleled feeling of awe, of majesty even, after pointing your telescope at what appears to be a blank patch of evening sky and then seeing—rendered in vivid detail on your computer screen—a wispy nebula or spiral galaxy surrounded by countless stars.

If you would have asked me 10 years ago if I thought I would be taking detailed pictures of incredibly faint and distant objects like WR 134 from my backyard in the East Bay Hills, I likely would have said no. Not least because until recently, I didn’t even own a telescope.

That’s not to say I wasn’t interested in the cosmos. Whereas most kids’ first scientific infatuation is dinosaurs, mine was space. In the mid-1980s, at the age of seven or eight, I got my first small telescope and quickly learned from my dad and uncle the basic architecture of the evening sky: the paths of the planets, the shapes of the major constellations, and the locations of many of the first-magnitude stars—Sirius, Vega, Rigel, Arcturus, Capella, their names resounding like poetry as I took in their crystalline light through the eyepiece.

But I knew there was more out there, hidden in the light-besmirched night skies above Denver. At night in bed, I marveled at the detailed pictures in my illustrated field guides of wispy nebulae, whirling spiral galaxies, and pointillistic star clusters. When the skies were clear, I could just make out the faintest wisps of the Andromeda Galaxy and the Hercules Cluster through my inexpensive refractor. Even then I understood that only long-exposure photographs could reveal their true structures. At the time, however, amateur astrophotography was virtually unheard of. Unless you had access to an observatory along with some seriously specialized equipment, detailed images of deep space were all but out of reach—particularly for someone not yet in the third grade.

Fast-forward 40 years: Tools once available only to professional astronomers are now within reach of everyday stargazers. Digital sensors have revolutionized the field and put the cosmos within reach of anyone with a digital camera or cell phone. And the results have been nothing short of miraculous. Indeed, the best amateur astrophotography, taken with specialized cameras and large telescopes from dark sky locations, rivals the images produced by observatories and even, dare I say, the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes.

But tonight there’s trouble on the horizon—literally. I live in the East Bay Hills above Richmond, and the fog has begun to creep through the Golden Gate, spilling over the triangular lump of Angel Island. It’s only a matter of time before it slithers up our hill and blots out the stars. The night is a lost cause. Preemptively, I plod into the backyard, dismantle my setup, and haul it back into the basement.

The San Francisco Bay Area is a notoriously difficult place for astronomy. Even on fog-free nights, other challenges loom. Because of our high humidity and cool nighttime temperatures, dew is always an obstacle. When temperatures plunge after sundown, the large lenses and mirrors of telescopes become collecting points for moisture, which, like a fogged-up car windshield, diminishes the view.

The biggest problem, however, is not unique to the Bay Area. Thousands of LED streetlights and outdoor floodlights burn and glimmer in the distance. The ceaseless stream of traffic on Interstate 80 and the glowing dome above San Francisco wash out the sky. But it is my neighbor’s motion-activated floodlight, with its sensor aimed indiscriminately into my backyard, that I most dread. When I step into a certain part of my yard, it blinks to life, as if activated by an invisible trip wire, showering the darkness with an effervescent glow of photons.

Light pollution is not merely an impediment to astronomy. It is a harmful, planet-altering waste—and we are learning that it has serious consequences for all living things on the planet. Light pollution throws animals off their migratory routes and changes their behavior. It also disrupts our circadian rhythms and contributes to myriad health problems. Notably, it suppresses the release of melatonin, which regulates our light-dark cycles. A lack of melatonin, in turn, contributes to increased stress, sleep deprivation, hypertension, even various forms of cancer.

Despite the Bay Area’s radiant (one might say radioactive) nighttime glow, I still love living here. But sometimes I wonder why I embarked on this nocturnal hobby given our atmospheric realities. When despair begins to set in, however, I remember the joy of pulling an object that is thousands, even millions of light-years away from the urban glow.

Which is to say, I’ll be back at it tomorrow night.

escaping light pollution

To escape the urban glow of San Francisco, check out the Bay Area’s many open-space parks and preserves where there’s refuge from the worst ravages of light pollution (though be sure to check local curfew rules). One of the best local dark sky locations is the summit of Mount Hamilton, home to the Mount Lick Observatory. Built in 1888, it was the world’s first mountaintop observatory accessible to researchers and visitors year-round.

Today, the sprawl of the South Bay encroaches on Mount Hamilton’s western slopes, and the night sky is far brighter than it was 135 years ago. Nevertheless, the skies remain dark enough to see dimmer stars. Under good viewing conditions, you can still detect the faint glow of the Milky Way.

Stargazers and telescope enthusiasts will want to set up in Point Reyes National Seashore. When the fog is at bay, Point Reyes offers some of the darkest skies in the region. Better yet, the seashore gives astronomers unparalleled views of the western night sky, which for many in the Bay Area is usually stained with stray light from San Francisco.

Astronomy is a somewhat monastic pursuit. The discoveries you make tend to happen in isolation—as does the technical suffering. But if you look hard enough you will find you are not alone, that there are other sleep-deprived practitioners out there, experiencing the same joys and enduring the same challenges in the rapidly retreating darkness.

A few years ago, I learned that my neighbor, John Alfonso, is an amateur astronomer. Unlike me, however, he doesn’t use cameras; he uses his eyes. Alfonso is not merely a stargazer—he’s a telescope maker. Over the years, he has built several powerful homemade scopes from scratch.

Recently, Alfonso invited me over to his house. Scattered across his kitchen table were faded photographs of the half dozen or so instruments he has constructed by hand over the years. His first foray into telescope-building came in 1958, when he was a freshman in high school. He talked his parents into sending away for a three-inch telescope kit from a company called Edmund Scientific. “They were kind of like Ford or Chevrolet for amateur astronomers,” Alfonso said.

A couple weeks later, a box arrived at their front door. What was inside was far more rudimentary than what he’d imagined. The box held a three-inch mirror, two small lenses for an eyepiece, and a secondary mirror. There was no tube to hold the mirror, nor were there any materials—wood or aluminum—to construct a rudimentary mount. “I couldn’t build it. Our family didn’t have any tools in the house,” he recalled. “So it just sat around.”

When Alfonso was in his 30s, he moved to the Bay Area, where he attended a local astronomy night. There, he met a noted amateur astronomer and comet hunter named Doug Berger, who invited him to a telescope-building workshop at Oakland’s Chabot Observatory, when it was still on Mountain Boulevard. (Berger gained momentary fame in the Bay Area in 1975 after his discovery of a comet.) “I just walked in and said, ‘Doug Berger gave me this flyer,’” Alfonso said. “They welcomed me with open arms.”

Immediately, Alfonso began work on a six-inch reflector. Over the course of several months, he painstakingly shaped the telescope’s mirror, scraping away at a raw piece of glass (known as a blank) with special tools and fine grains of special lens-making sand. “It took forever,” he said, but eventually the flat glass disc morphed into a precisely shaped concave mirror. Satisfied with his work, he decided to test the mirror, setting it into place in the white cardboard tube. Then he plopped in an eyepiece and aimed the scope at Saturn. The mirror hadn’t yet received its final silver coating and Alfonso wasn’t expecting to see much more than a bright, fuzzy blob. But when he peered through the eyepiece he was stunned. “The rings were clear as day,” he said. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is a real telescope.’” (It was so well made, in fact, that it won an award at a space convention in San Francisco.)

He was hooked and set out to build a larger, more powerful telescope—a Dobsonian reflector. The “Dob,” as it is commonly referred to, is named for the amateur astronomer John Dobson. A roving eccentric and former Vedanta monk, Dobson was a tireless promoter of science and a true Bay Area original. In the late 1960s, he and a few telescope enthusiasts founded a group in the Presidio called the San Francisco Sidewalk Astronomers. Their mission was to teach people to see the wonders of the universe through cheap but powerful homemade telescopes.

The group still exists and carries out what they call “urban guerilla astronomy,” giving public astronomy demonstrations on street corners and in front of movie theaters and shopping malls to carry on Dobson’s lifelong mission: to show that through the lens of a powerful telescope the wonders of the cosmos are still within reach of city dwellers.

A Dobsonian reflector is not what most people expect when they think of a telescope. The homemade versions, like Alfonso’s, are built of wood and rough metal and other odds and ends that can be found at any local hardware store. Instead of a conventional tripod, the scope rests on a plywood box. In its current form, the telescope has no tube. Rather, its mirrors are supported by a half dozen or so pieces of aluminum pipe.

Alfonso adjusts his Dobsonian telescope in his garage in Richmond. The telescope was built by hand in the 1980s. (Jeremy Miller)

But on a cloudless summer night during the pandemic, Alfonso showed just what his ungainly-looking scope is capable of. Our neighbors queued up, masked, glasses of wine in hand, as he trained the scope on a bright dot suspended in the clear night sky. The bright dot was Saturn. With a few deft nudges, he brought the object into view. “There we go,” he said as he gently twisted the focus knob. One of my neighbors, a lanky professor of ancient language studies at the University of California, was the first to hunch down and peer through the lens.

“My god,” he said. “It looks like you could touch it.”

When I finally had my turn at the eyepiece, I could hardly believe what I saw. Like a small jewel, the planet hung in the dark void of space, quivering ever so slightly due to atmospheric turbulence. This was far from my first glimpse of Saturn, but through Alfonso’s homemade scope, it was as if I were seeing the planet anew.

The delicate, pastel bands of the planet’s atmosphere were bright and pronounced, as were the rings, which looked almost three-dimensional. Several bright spheres along with many precise pinpricks of light glimmered around the planet. These were but a handful of Saturn’s 146 known moons. Most impressive of all was the so-called Cassini Division, a large black gap separating Saturn’s inner and outer rings. (This structure is named for the Italian-born astronomer Giovanni Cassini, who documented it in the late 17th century.) The division was so well defined through Alfonso’s scope that it looked as if it had been sketched in with a Sharpie.

I pulled my eye away from the lens and looked in awe at the homemade Dob on its humble plywood pedestal. With its large magnification and massive light-collecting capabilities, the telescope gives much clearer views than my own store-bought scopes can produce.

Back at his kitchen table, I asked Alfonso to describe the allure of visual astronomy. “If you’re under a dark sky and look at the Orion Nebula, you can just start to see some greens and reds,” he said. “That’s pretty exciting.”

But Alfonso doesn’t set up the scope much anymore. He’s less keen these days on hauling out his Dob, which weighs around 90 pounds, to dark sky locations around the Bay Area. And the light pollution in the neighborhood has made it mostly not worth the effort of setting up his scope in his driveway. “The sky is getting worse,” he said.

I ask Alfonso if he’s considered a more compact setup like mine, with sensitive camera sensors and filters that can help counteract urban light pollution. He replies that he thinks the advances in astrophotography are incredible, but it’s not what thrills him. “I would rather just see what I can,” he said. “I don’t mind that I see less. The fact that those photons that have been traveling, let’s say, from the Andromeda Galaxy, two and a half million light-years away, and those photons are hitting me right in the eye—that’s the draw.”

It’s late October and I’m in the backyard again. My scope is set up and the clouds have lifted. The forecast is promising for the next few days—clear with low humidity. I will need every hour I can get.

I quickly orient the mount to the North Star, or Polaris, around which the night sky spins like a top. On my computer, I give a command to move to the Wolf-Rayet star WR 134. As the telescope whirls into place, a barn owl on its nightly round issues its eerie, shrieking call. This call-response is common. Though I can’t be sure, I have come to believe that the owl thinks my telescope mount, with its shrill metallic whine, is one of its own.

Now comes the moment of truth: I set the camera to take a single eight-minute exposure. Suddenly, wispy waves of interstellar gas appear on the computer screen. I’m elated as the images accumulate and the unmistakable nautilus-shell-like structure of WR 134 comes into view.

The final composite photo, made up of more than 100 individual images, reveals a scene that no human eye could perceive.

But is it more real?

As I tinker with the final image’s color and contrast, John Alfonso’s words ring in my mind. I think about the fact that the ancient photons did not strike my eye directly but accumulated on the silicon retina of the camera. Every image has been mediated through a microprocessor, turned to ones and zeros before being spat out as digital photons on my computer screen. There is also a particular irony in the fact that the blue light emitted from my monitor is a potent melatonin suppressor. Which is to say, my digital astronomy produces its own kind of light pollution.

As much as I love my telescope and camera gear—consumer-grade cousins of the Hubble and James Webb Telescopes—I am starting to think that the technology has also made me somewhat passive. My light pollution filters and software are indeed amazing scientific tools, but they are also a means of coping with rather than confronting the situation at hand.

This, I think, is the deeper meaning of Dobson’s and Alfonso’s pursuit. Visual astronomy forces you to look, to confront reality with your own eyes. So, when I next head out to my backyard, I will take a different approach. I will remove the digital camera and replace it with an eyepiece. As in my early days, I will use only my eyes. I will peer through the orange glare of San Francisco in search of ancient light. I will see what I can see.

LEARN MORE

The basics of astrophotography

Astrophotography can seem a daunting, expensive hobby, but there are a few basic pieces of equipment that will get you started quickly and without the need to spend thousands of dollars. You may be surprised to learn that a telescope is not a requisite piece of gear. A DSLR camera and lens can be the foundation of an effective astrophotography setup. (Some outstanding images have been produced with relatively inexpensive digital cameras and lenses.)

A good way to learn the basics of astrophotography is to join an outing with a local astronomy group. There are several in the Bay Area, including the Eastbay Astronomical Society, the San Francisco Amateur Astronomers, and the San Jose Astronomical Association. Attend a star party or astronomy event and learn from local astronomers who have jumped headfirst into this difficult but most rewarding hobby.