A new tree nursery is sprouting in San Francisco’s SoMa neighborhood. Unexpectedly, it’s under Interstate 80. All around the skinny trees, the highway piers shudder, and the cars thunder by overhead. Reclaiming this little triangle of land to grow trees for San Francisco’s streets has a bit of a David and Goliath feel—as if David were thumbing his nose at the Goliath of the car culture and fossil-fuel industry that have largely driven the climate crisis. It hardly seems like a nurturing place.

Amid the concrete, little trees grow. An artist’s rendering shows plans for San Francisco’s new nursery; a ‘before’ shot shows its barren beginnings. The nursery opened Nov. 9. (Courtesy of San Francisco Public Works)

Yet Jon Swae’s excitement is infectious. “We’re transforming this vacant parcel at the base of an enormous carbon-emitting freeway to grow trees for climate equity,” he says. Swae, a grants manager for San Francisco’s urban forestry bureau, is overseeing the nursery’s launch. The 1,000 trees that will be grown here, including native coast live oak grown from San Bruno Mountain acorns, and California buckeye from Yerba Buena Island nuts, are meant to be mega-multi-taskers. In the years to come, Swae says, “we will have improved the quality of life for more San Francisco residents with mental health benefits [and] spiritual benefits, as well as environmental and climate benefits.”

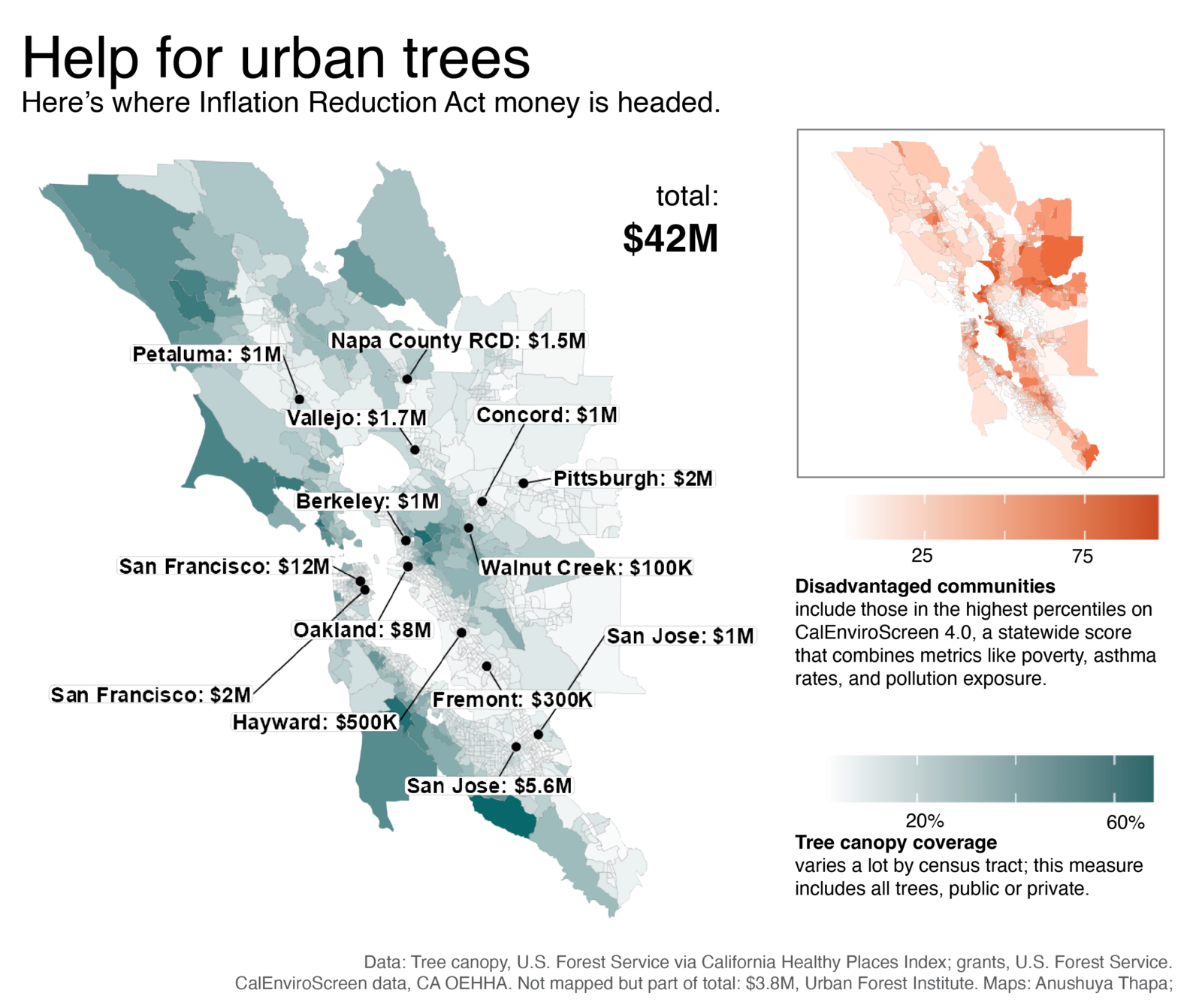

It’s all part of an enormous nationwide push to plant more trees in cities. In the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Congress allocated $1.5 billion for grants via the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service. Thirteen cities or local organizations around the San Francisco Bay are receiving a total of $42 million from the Forest Service’s Urban and Community Forestry Program, out of $104 million granted across California.

The tree need is very, very great

Days before she died in September, U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein said in announcing California’s 43 awards, “Planting trees is one of the best tools we have to fight climate change and protect residents from extreme heat, yet too many of our urban areas lack sufficient tree canopies.”

This “tree equity” or “canopy equity” gap, as it’s known, persists around the Bay—with the thinnest tree coverage in the more industrialized flats close to the shoreline. By and large, these neighborhoods have experienced generations of environmental injustice, much of it stemming from racial discrimination in housing and infrastructure development. Says Sara Davis, San José’s first urban forester: “There’s a lot of history that goes into why certain neighborhoods have green amenities and others don’t, going back to racist redlining housing policies and where interstate highways were established.” Planting trees helps mitigate the negative impacts of these discriminatory policies on the surrounding communities.

This story is part of Wild Billions, a Bay Nature project exploring the impact of big federal money on Bay Area nature.

More on urban trees in this series:

- Oakland’s Urban Tree Dreams Get (Partially) Funded

- Oakland Offers a Plan to Aid Its Troubled, Unequal Tree Canopy

These urban forestry grants, like other IRA programs, are prioritizing environmental justice and climate equity. “These funds give us an opportunity to expand our work on a scale that is exciting and absolutely needed,” says Miranda Hutten, who oversees California’s grants as the USDA’s urban and community forestry manager for the Pacific Southwest region.

But this money won’t solve all the problems. For this round of funding, Hutten says, the program received applications totaling $6 billion, way more than the $1 billion the agency had to give—in part, she suspects, because the agency waived a requirement for matching funds that is a barrier for many disadvantaged communities. Most grantees only got 25 to 30 percent of what they asked for—which means they’ll have to revise their plans to do less.

Still, when IRA was enacted, Hutten says, “with a stroke of a pen, we went from a $30–40 million a year program for the last 30 years to a $1.5 billion program.” With that huge infusion of funds for urban forestry she says, the agency expects it can now engage potential grantees who may not previously have received federal funds.

Right tree, right place, right reason

Urban forestry is not about restoring or conserving historic ecosystems. It’s really about engineering a more habitable urban landscape in the face of climate change, especially as cities heat up. “California is going to be a harsher place to live,” says May Reid-Marr, project manager at the nonprofit Urban Forest Institute, which received a $3.8 million USDA grants.

In San Francisco, trees are a relatively recent addition to the landscape, as Brian Wiedenmeier, Friends of the Urban Forest executive director, points out. “Unlike some U.S. cities, this is not naturally a landscape that was forested or that wants to be forested.” Before Spanish colonization and subsequent urbanization, Bay Area landscapes were dominated by coastal scrub and grasslands, with woodland pockets in the hills. And many of the communities targeted for tree-planting, like the west side of Berkeley and Hayward and the east side of San Francisco, are on land created when the Bay was filled in to create ports, airports, and other industrial and military sites during the 20th century. Here, there is no natural landscape to restore.

The City of Hayward aims to increase its tree canopy, like this shady part of Tennyson Road. (Helen J. Doyle)

But, as foresters often say, you have to put the right tree in the right place. Hutten adds “right reason” to this mantra. “If you’re interested in carbon sequestration, you need trees with thick trunks to hold carbon,” she says. “If you want to clean the air, you need trees with lots of leaves to remove particulate matter from the air. If you want to filter or hold back stormwater, you need trees with established root systems.”

The Urban Forest Institute’s grant is to help with the “right tree” problem. The organization is making tools integrating climate and forestry science to identify which trees are likely to thrive where—so-called “climate-adapted” trees. “Places where it’s hard to grow trees align with low-income communities, which are also vulnerable to the negative health impacts of climate change, extreme heat events, and respiratory impacts,” says Reid-Marr. UFI aims to support the efforts of municipalities and arborists throughout California, particularly areas with limited funding, to select trees and to aggregate statewide data about what trees survive well over time. “We need to plant massive numbers of the right trees by making specific, data-driven choices.”

This is a long game: it’ll take decades before all the trees planted have grown enough to provide all the ecosystem services we need from them—which means it’ll take years to measure the success of this program. In the meantime, though, the USDA is looking at “other metrics of success—such as the relationships built and the communities empowered to take action in response to the climate crisis,” Hutten says.

A roundup of tree grants around the Bay

How do cities know where the biggest tree needs are? Mapping tools like the new federal Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool and CalEnviroScreen help identify communities bearing the greatest economic and environmental impacts of the climate crisis. Nearly always, these are also the low-canopy neighborhoods.

Measures of urban tree canopy count all the trees, not just city ones—street trees, trees in parks, trees on private property. Most of this grant money is focused on sidewalk and street trees, though the San Francisco and San José parks departments also received awards. Maintenance of such “public right of way” trees is often the responsibility of the property owner, a less-than-ideal situation for the tree. In some cases, the awards will allow a city to assess maintenance costs and build support for dedicated funding, as San Francisco achieved in 2016 when voters approved a property tax to pay for street tree maintenance.

Here’s a look at how some cities around the Bay are planning to spend their grant money.

Berkeley

In Berkeley’s flats, few trees are visible from the corner of Ashby and San Pablo avenues. This neighborhood, along with others on the city’s west and south sides, is a priority for planting climate-adapted trees with the city’s $1 million grant. Berkeley has over 35,000 trees, yet there are 10,000 empty potential tree planting sites, estimates Ian Kesterson, Berkeley’s planting program manager. “Tree canopy cover varies from 40 percent in the Berkeley hills to just 10 percent in the flats,” he says. And the mixed residential-industrial areas in the flats rely on the city to plant trees more than the residential hills where private yards provide space for trees to thrive, he says. The city plans to use the grant to fill up the city’s main boulevards and high-traffic bike and walkways. “People always walk on the shadiest side of the block. We’ll let the trees promote the opportunity for people to get trees in their neighborhoods,” Kesterson says.

Fremont

Following its first-ever tree inventory and adoption of a new Community Forest Plan in April, Fremont aims to use its $380,000 grant to start increasing its tree canopy from the current 14–15 percent to 24 percent coverage. Urban Forestry Manager Chris Curry says the city needs to plant thousands of “the right trees in the right places to expand the canopy” and replace those lost through aging and poor management. In addition to the trees, though, he’s excited that this grant will provide “on-the-job green infrastructure workforce training, to ensure we have local young people with experience in sustainable urban forestry.”

Hayward

Todd Rullman, city maintenance services director, and his colleague Rich Nield, landscape division manager, each have decades of experience living and working in Hayward. They know its streets and trees well. But they don’t know all 30,000 trees or all the locations where tree canopy could be increased. Hayward got a $500,000 grant for a software system to integrate tree inventory, carbon sequestration data, and urban tree canopy assessments. It’s intended to improve tree maintenance and identify prime sites for new trees. Like many cities around the Bay, Hayward is criss-crossed by freeways and bridge ramps. Nield points to a now-shady median on Tennyson Road as an example of the greening his group has done with the community and plans to extend through areas of lower income and multi-family homes. A sense of fairness motivates the project. “Just because you didn’t spend a million and half dollars on your house doesn’t mean the median of the road leading to your house should be barren,” Rullman says.

Oakland

Oakland got one of the biggest grants in the area—$8 million. But Oakland also has some very big tree problems. Following the 2008 recession, the Oakland City Council cut all tree-planting and pruning from its budget, and never restored the programs. Now, Oakland loses roughly 6,000 trees every year—and they’re not being replaced. In one 2020 study, a group of scientists found Oakland had the most unequally distributed tree canopy of the 40 U.S. cities they examined. The city hopes to turn that around, and has released a new urban forest plan, which is open for public comment until Dec. 8.

The $8 million award is meant to jump-start the plan, and will pay for planting and maintaining trees in disadvantaged neighborhoods. The city is partnering with two nonprofits, Common Vision, a West Oakland nonprofit that aims to plant fruit tree orchards in low-income schools, and Oakland Parks and Recreation, to carry out this work.

San Francisco

San Francisco has some of the most paltry urban tree coverage in the nation, with less than 14 percent tree cover, according to the city’s 2014 Urban Forest Master Plan. And every year, the city loses more trees to development, poor maintenance, or natural causes than it is planting. The city is getting $12 million to focus “100 percent on ‘priority equity’ neighborhoods such as Chinatown, Tenderloin, SoMa, Bay View, and other southeast communities,” Swae says.

In addition to planting trees, “we also know we need to build support for trees and trust in neighborhoods that may not already be clamoring for trees.” Urban foresters don’t assume everyone would like a tree in front of their home or business. City sidewalks where trees might go are sometimes used for parking or outdoor eating. Some residents are worried they’ll get stuck with tree maintenance, and they may be concerned about “green gentrification,” in which neighborhoods with more nature become more desirable and expensive. As part of its community engagement efforts, San Francisco is also dedicating funds for job training in urban forestry, in collaboration with Friends of the Urban Forest.

San Francisco’s Recreation and Parks Department also received $2 million to expand tree canopy in parks on the city’s southeast side, such as John McLaren Park, Bay View Park, the new India Basin Waterfront Parks, and a myriad of neighborhood playgrounds and mini-parks. According to Daniel Montes, parks department communications manager, this is already the hottest and sunniest area of the city—and will be the most affected by climate change. “We need to plant trees now to have the urban canopy we need to mitigate the effects of the climate crisis in decades to come.” Workforce development is also a significant component. “We want to recruit and cultivate talent from the neighborhoods where we are doing this work.”

San José

San José is a large city at 180 square miles, with tree canopy averaging just 14 percent. Between 2012 and 2018, the city lost nearly 2 percent of its tree cover, the equivalent of losing three square miles of trees, according to its 2022 Community Forestry Management Plan. With San José’s $5.6 million award, city forester Davis hopes to plant 2,800 trees in 78 census tracts that lack trees, survey the city’s existing tree canopy, and evaluate maintenance needs and costs. Davis also notes that trees that are native to our region don’t tend to do well in cities. “We’re looking south for species we can plant now and that will be tolerant of the climate we have in 30 years, adapted to absorbing a lot of reflected heat.”

San José’s Parks, Recreation, and Neighborhood Services department also received $1 million for tree management and community engagement in Alum Rock and Overfelt Gardens parks. In addition to replacing older trees with climate-adapted ones, this project will provide volunteer, education, and job training opportunities for San José residents.

Vallejo

Vallejo received $1.7 million for a waterfront revival that will incorporate native, drought-tolerant trees and water-smart irrigation into multiple city landscaping projects, including a new cultural garden. Sidney Wilson, a city administrative analyst, wrote that the project will transform barren dirt areas along the city’s waterfront into some 20 acres of new green space near the ferry terminal. City officials hope to increase waterfront access and usability, while building habitat that sustains trees, local birds, bees, butterflies, insects, and animals. Ultimately, the project will connect the Bay Trail and Vine Trail, linking public open spaces and encouraging walking, biking, and ferry riding.

More money to come

For those who did not get funded this round, Cal Fire (the state’s Department of Forestry and Fire Protection) will award an additional $30 million from the USDA’s IRA funds to smaller cities, community-based organizations, and tribal agencies. Rachel O’Leary, Cal Fire’s new partnership and equity coordinator, wants “to reduce barriers and make it easier to access these funds” for tribal groups and other disadvantaged communities. She says urban forestry is the simplest and most cost-effective solution to extreme heat from climate change. And she says Cal Fire needs to be responsive and flexible to meet the needs and goals of individual communities.

Hutten, of the USDA, says these projects are about more than just planting trees. Trees take a long time to pay off dividends. “We know we can’t plant ourselves out of this climate challenge,” she says. “If we don’t listen to the community and make sure they are part of the process, these trees won’t be planted, cared for, or valued. I want this to be an ongoing conversation with the communities that are facing the greatest burdens from the climate crisis.”

Lia Keener contributed reporting on the Oakland grant.