Before visiting Tolay Lake, check details with Sonoma County Regional Parks

A relative told me that when she saw Tom Smith’s charmstone, she was temporarily blinded and felt instantly faint—its power was that overwhelming. The charmstone, an oblong, smoothly carved rock figure, about an inch and a half in length, was loosed from Tom Smith’s “doctoring kit,” which had been stored in a drawer at UC Berkeley’s Lowie Museum for decades following his death in 1934. Grandpa Tom, as he is known in the family—he was my great-great grandfather—reputedly caused the 1906 earthquake in a contest of power with another medicine man. Like other medicine men and women from Central California and beyond, Grandpa Tom, a Coast Miwok, used charmstones when doctoring the sick, for luck in fishing and hunting, and who knows what else—perhaps even causing an earthquake.

Mabel McKay, the late renowned Pomo basket-maker and medicine woman, witnessed a Lake County Indian doctor pulling a tiny rabbit from a sick woman’s chest using a thumb-size quartz amulet; Mabel herself gave a troubled young man a charmstone to keep an evil spirit at bay. Maria Copa, a Coast Miwok born at Nicasio, told ethnographer Isabel Kelly that a charmstone had followed a woman home and that the woman had “to hit it three times” with a stick to kill it. When American rancher William Bihler dynamited the southern end of Tolay Lake in the early 1870s, draining the rather large but shallow lake of water, what the muddy bottom revealed was thousands upon thousands of charmstones—far more than found in any one locale in North America.

Roughly seven miles east of Petaluma, Tolay is the southernmost and largest in a chain of lakes tucked within the Sonoma Mountain range. You might imagine it the pendant at the end of the chain. Standing on the ridges above the lake, you can see the emerald expanse of San Pablo Bay spreading before you, and like a sculpture rising from the water, San Francisco’s Financial District, and then four of the Bay’s major mountains: Mount Saint Helena, Mount Tamalpais, Mount Diablo, and Mount Burdell. All of the lakes in the chain were shallow, even more shallow than Tolay, hardly 20 feet in its deepest spot, but, like Tolay, all of the lakes contained water year round, until after European contact, when the water table in the region dropped 20 to 30 feet in a relatively short period of time.

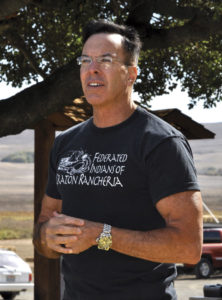

My ancestors occupied the region. Today we are known as the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, descendants of natives identified by early ethnographers as Southern Pomo and Coast Miwok. These are names based on language families: Southern Pomo, a member of the Hokan family; Coast Miwok belonging to the Penutian family. Southern Pomo, with its own various dialects, was spoken from the Santa Rosa plain north, and Coast Miwok southward to and including present-day Sausalito. But until recently, and for purposes of our relationship with the federal government, we never referred to ourselves as Pomo or Coast Miwok. We belonged to one of over a dozen separate nation-states, each composed of 500 to 2,000 individuals, with one or more central villages and clearly defined national boundaries. Most people, regardless of their national affiliation, spoke several languages, some of these languages perhaps quite different from one another—Pomo is as different from Coast Miwok as English is from Urdu.

What we’ve always known is that Tolay Lake was a great place of healing and renewal, that Indian doctors came from near and far to confer with one another and to heal the sick.

Tolay Lake is in the heartland of the Alaguali Nation, whose principal village, Cholequibit, sat southeast of the lake, bordering San Pablo Bay. The Alaguali knew their homeland intimately; typical of Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo Nations, they practiced controlled burning, maintaining grasslands for elk and pronghorn. They cleared waterways for fishing and hunting waterfowl and cultivated sedge beds, growing long, straight roots for basket-making. From the San Pablo marshes, they fished sturgeon and bat rays. Each nation, it seemed, had something unique that was needed by others. A Southern Pomo Nation near Santa Rosa mined obsidian prized for arrow-making. Southern Pomo and Coast Miwok along the Laguna de Santa Rosa grew the finest sedge. The lagoon was full of perch and bass year round. The Petaluma Nation’s vast plains contained the largest herds of elk and deer. The Alaguali had the lake.

It wasn’t only local indigenous nations who cherished the lake. Charmstones discovered in the lake bed came from a multitude of places throughout California, and from as far away as Mexico. Many are over 4,000 years old. Certainly California Indians had extensive trade routes. More, the so-called discovery of these charmstones becomes evidence for the stories that continue to be passed down in our families. What we’ve always known is that Tolay Lake was a great place of healing and renewal, that Indian doctors came from near and far to confer with one another and to heal the sick. Members of a village at the southern end of the lake, not far from Cholequibit, hosted the visitors in several special houses made for fasting and ceremony.

Charmstones vary in length, but most are about 2 to 3 inches long, and most are oblong. Some are simply rounded; the specific shapes of others might suggest a phallic design, prompting some ethnographers and casual observers to think these charmstones were used in fertility rites. Sinkholes bored through some suggest they might’ve been used for fishing, specifically for anchoring nets. Whatever else charmstones may have been used for, they were used by medicine people to extract illness. The charmstone, in a sense, inherited the sickness, and it had to be destroyed. Drowning was the usual method, whether in Tolay Lake or another body of water. Maria Copa’s story reminds us the charmstones were considered living beings—they possessed living spirits like all of the material world. A person could use a charmstone—and the sickness it took from an ill person—to harm another person.

Some of what we know about the Alaguali Nation and area comes from historic records. Father Abella, a Franciscan from Mission Dolores, baptized two elders from the village of Cholequibit in 1811. Randall T. Milliken’s meticulous study of mission records indicates that between 1811 and 1818, 151 Alagualic people were baptized—91 at Mission Dolores and 37 at Mission San Jose. Father Jose Altimira, traveling in 1823 from the Presidio in San Francisco to establish Mission San Francisco Solano in present-day Sonoma, stopped near the lake and noted in his journal that the surrounding hills would provide plenty of grass for cattle grazing and that the lake was named after “the chief of the Indians,” called Tola.

The landscape, already altered, continued to change, in many places beyond recognition for a person living a generation before. The great herds of elk and pronghorn continued to disappear. Flocks of waterfowl, once rising from the waterways so thick as to block the sun, thinned. Native bunchgrasses, like purple needlegrass, were overrun by European oat grass, spread from seeds in the dung of Spanish and Mexican livestock. After the missions were secularized in 1834, the natives worked for General Vallejo on his Rancho Petaluma, which included Tolay Lake, mostly in some form of indentured servitude, tending his cattle and planting crops.

It was no coincidence, although it was sadly ironic, that General Vallejo, defeated by Americans in the Bear Flag Revolt, helped California lawmakers draft, during their first legislative session in 1850, An Act for the Government and Protection of Indians that legalized Indian slavery—and was not repealed in its entirety until 1937. Indians were separated from families but their aboriginal villages persevered, even as our numbers dropped precipitously. We continued to eat many of our native foods, most notably acorn mush, and continued older religious practices. We made herculean efforts to maintain families, even as the aforementioned 1850 act provided loopholes for Americans to steal our children. J. B. Lewis, an American rancher, who in the 1850s owned land north of Tolay Lake, noticed that Indians—he thought from a local tribe—“stayed a day or two [at the lake] and had some kind of powwow.” It was only after William Bihler dynamited the southern end of the lake 20 years later that there were no reports of Indians returning.

At the time of European contact, the combined population of Southern Pomo and Coast Miwok Nations was about 20,000. Some estimates go much higher. Central California, the Bay Area in particular, was home to the densest population of indigenous peoples in North America outside of Mexico City, site of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán. Ethnographers have often wondered how so many people living so close together speaking so many different languages got along with virtually little physical warfare for 10,000 years—yes, we’ve been here that long. From atop the ridges surrounding lake Tolay, we watched the Bay grow as it filled with water from the melting glacial ice caps. Believing that everything in nature was alive—and had power—you had to be careful not to mistreat or insult even the smallest pebble on your path. Likewise, people had power, often secret power. Secret songs, spirit guides, and objects such as charmstones protected a person and could be used against one’s enemies. If you had to physically assault another person, you revealed that you had no secret power. Physical warfare thus was seen as the lowest form of war since it would suggest that you possessed no spiritual power and could be attacked without worry of retribution.

Ethnographers saw the culture as predicated on black magic and fear. Rather, the culture was predicated on profound respect: You had to be mindful of all life, reminded always that you were not the center of the universe but a part of it. Sickness, whether caused by another human being or from a bird or a simple rock, dislocated one from the world, resulting in, if not continuing, imbalance. Medicine men and women drowned the charmstones to put away the sicknesses that were taken from patients. The sickness was put away and the patient—and the natural world of which the patient was a part—was renewed. Knowing the lake was drained of water and the charmstones exposed, did the Indians fear returning?

For the past several years, the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria have held their summer picnic at Tolay Lake. We gather to enjoy food and reconnect with family. Booths offer information on language and basketry classes. At one booth, we can trace our ancestry to one or more of 14 survivors from whom we all descend. Children can visit goats and chickens inside the restored barns. Hayrides take us across the dry lake bed and up onto the mountain ridges. Yet even as I give my welcoming speech as Tribal Chairman extolling the virtue of our gathering again in a sacred place, I’ve often wondered if it is such a good idea for us to be here. The Cardozas gathered charmstones as they planted pumpkins, leaving the lake bed bare—and for a long time displayed the stones in buckets during the Fall Festival. But might not disease and sickness remain in the soil, in the humid air that rises from the lake?

On hayrides, I watch as relatives and friends point from the ridgetops and name ancient villages. “There,” a young woman says, looking south below the lake. “Cholequibit. The priest baptized a man and his wife there and named them Isidro and Isidra. They are my ancestors.” Another young woman looks west and points. “Olompali. My ancestors are from there. [The priest] baptized them Otilio and Otilia.” So many of our people have been lost as a consequence of an ugly history. Too many have lived—often difficult lives—and died with little sense of the homeland, much less of the sacred lake. Seeing these young women and others, some of whom are taking in the views for the first time, I understand something about renewal—about what must have occurred as Indian doctors and their patients left the lake. Didn’t the ridgetop views confirm healing, that one was located in place again? Even if Grandpa Tom didn’t return to the lake after it was drained, might not he have climbed a ridge to remember Petaluma, the birthplace of his mother?

During a lull in this past winter’s endless rain, I went to Tolay. The lake collects water during the winter months, and with the abundant rain, I thought I might see the lake as it once was—or maybe close to what it once was. Archaeologists have noted that the lake’s southern membrane was thin, suggesting that people of Alaguali maintained a dam, no doubt regulating waterflow from the lake. I found the water was high, extending from just below the farms’ barns to the opposite end of the valley below the hills. A lone osprey flew overhead. Mud hens and mallards bobbed on the muddy water. Under a cloudy sky, I stood and tossed a small piece of angelica root into the water to appease the spirits. I figured if the lake’s ridges helped locate my people, then the story of the lake and its charmstones can remind us again of the power within all life. Yes, I thought, imbue reverence.

Then, as I was walking back to my car parked behind the gate above the lake, I began to wonder about my people who might not believe the story. And what of non-Indians who haven’t yet heard it? Might not fooling around the lake be dangerous? Thinking has its clever way of taking me out of the moment, and here I was thinking again, lost. Until I reached my car. The sky opened and silvery sunlight covered the land around me. The four mountains in the distance remained covered in the shadow; they seemed to grow out of the land like huge fingers. The lake was below me, flat and broad. All at once I understood something else, or rather I felt it. In that brief moment before the clouds shielded the sun again, I felt what it was like to be held. I was standing in the earth’s enormous hand.

.jpg)