Mike Westphal pauses at a rise above Highway 1, a mile north of the tiny town of Davenport on the Santa Cruz County coast. “Here we are,” says Westphal, a biologist with the Bureau of Land Management, as he looks out over a muddy pasture enclosed by a barbed-wire fence. Nine circular ponds, each about 20 feet across, are arranged in a triangle, like the footprint of a giant set of bowling pins, over about an acre of land. “Behold,” he says, with a jokey sweep of his arm. “My empire.”

As empires go, Westphal’s is modest. The scene in front of us seems like way less of a candidate for beholding than the one at our backs: the gray ribbon of Highway 1, cliffs falling to Scott Creek Beach, and the Pacific Ocean stretching to the horizon, its surface placid enough to reflect the clouds lingering from the morning’s rainstorm.

It’s the sort of textbook California vista that draws people from around the Bay Area and beyond to this sparsely populated stretch of the coast north of Santa Cruz. But outside of a few state parks—including part of Wilder Ranch and the Skyline-to-the-Sea Trail in Big Basin—there aren’t many recreational opportunities accessible from the inland side of the highway.

Helping the public explore this scenic area is part of what inspired the nonprofit Trust for Public Land (TPL) to purchase a 7,000-acre expanse of beaches, coastal prairie, and forests surrounding Davenport back in 1998. The project’s backers also intended to conserve the plants and animals that call this land home. But balancing these dual motivations—recreation and conservation—has proven an elusive goal: a quarter century after the land was first protected, locals and land managers still haven’t agreed on a plan to open the property to the public for daily use.

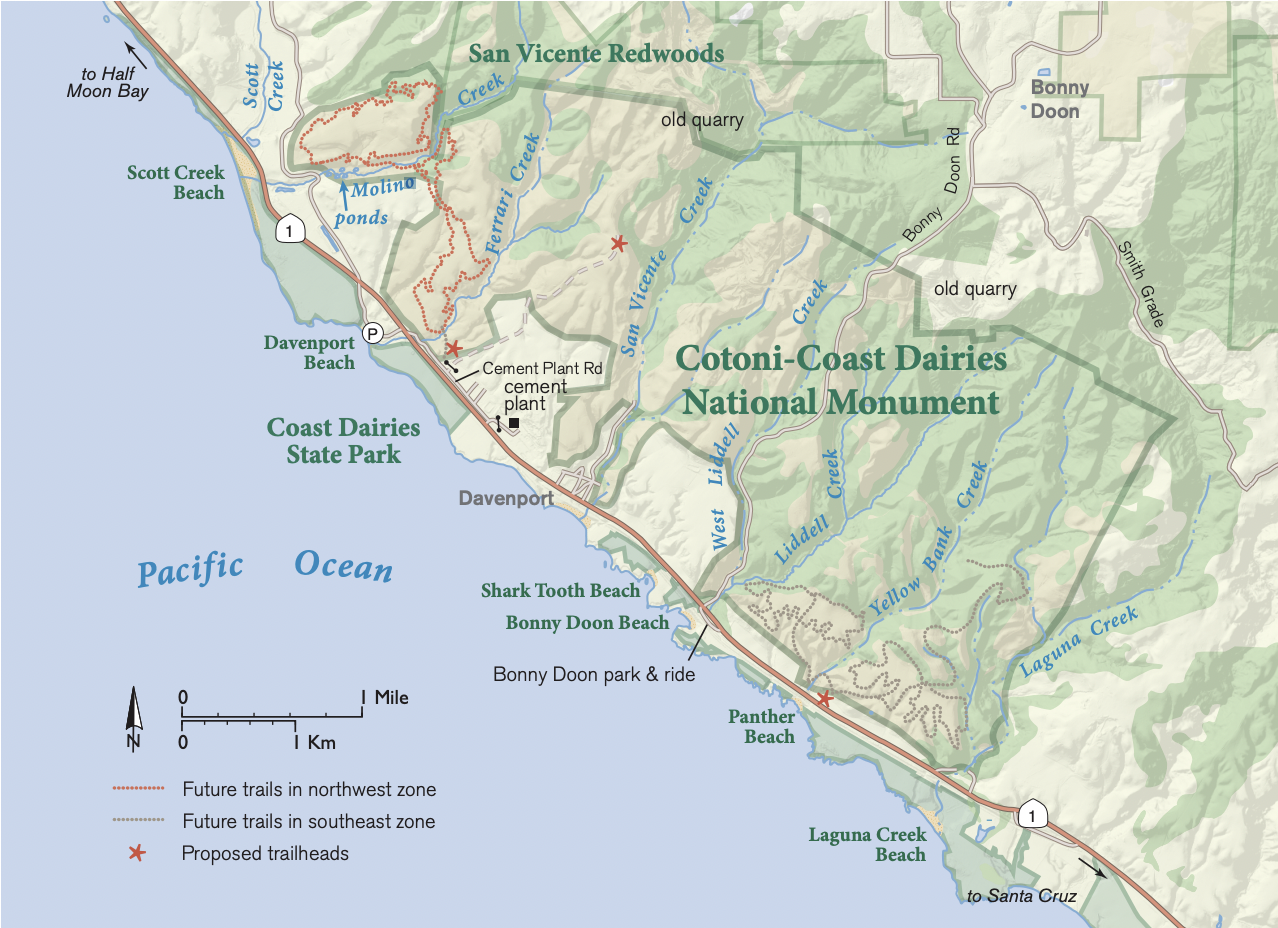

TPL eventually transferred 400 acres west of Highway 1 to California State Parks and nearly 6,000 acres east of the highway to the Bureau of Land Management. President Obama designated the inland share as the Cotoni-Coast Dairies unit of the California Coastal National Monument in 2017. Following a two-year planning process, the monument was slated to open in the fall of 2022. But that deadline has come and gone while the BLM navigates objections to the agency’s plan for public access.

A red-legged frog stronghold

Meanwhile, Westphal and his BLM colleagues are learning about the land’s history and resources. In partnership with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, the BLM is preserving cultural sites created by the Indigenous Cotoni (Cho-toe-nee) people, who lived on and around the present-day monument thousands of years before Spanish colonization in the late 1700s. Managers are using what they learn to begin restoring habitat and conserving archaeological sites across an ecologically diverse landscape that’s seen over a century’s worth of industrial use—and that faces new threats from climate-driven hazards like drought and wildfire.

Westphal says these nine ponds dug into a pasture above Molino Creek could be the start of a more secure future for one species of particular concern, the California red-legged frog. The biggest native frog species found in the western U.S., California red-legged frogs were once common between the Sierra Nevada foothills and the coast and from Mendocino County to Baja California. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the frog as threatened in 1996, finding that it had disappeared from 70 percent of its range owing to habitat loss and competition and predation from nonnative species.

But this cool, foggy stretch of coast has persisted as a “stronghold” for the species, Westphal says. “Until pretty recently, you’d go out to any stock pond or suitable stream between Santa Cruz and Half Moon Bay, and you’d have a pretty good chance of finding red-legged frogs,” he says. And within that stronghold, Cotoni-Coast Dairies, where six creeks reach the ocean along just six miles of coastline, is “really the beating heart of red-legged frogs as a species.”

But even in their innermost sanctum, the frogs might soon be fighting for survival. Drought has caused streams to run low and ponds to evaporate, leaving fewer patches of frog habitat and less time for eggs to hatch and grow into adults. What’s more, decades of ranching, quarrying, water diversion, and road construction have interrupted natural processes that frogs rely on to evade predators.

Throughout the 20th century, for instance, a series of cement companies quarried limestone and shale within the San Vicente and Liddell Creek drainages. The operation wound down in 2010, but its scars remain. Westphal points to the possible traces of one such injury in San Vicente Creek, where runoff from one of the winter’s first big rainstorms drains down a wide, straight streambed. “This looks to me like they just drove a dozer right down the middle of the creek back in the cement plant days.”

Once bulldozed, creeks like this one no longer meander to form oxbows that might eventually turn into red-legged frog ponds. Eventually such oxbow ponds might also attract rough-skinned newts, which are native to the Santa Cruz coast and eat red-legged frog eggs. But newts don’t disperse from their natal ponds as widely as their frog prey, so they’re typically slower to arrive in a new patch of habitat. Biologists hypothesize that frogs only live in a new pond for a few years before it silts up or gets colonized by newts. By then the creek would have created a new pond for the frogs to discover. “If this whole creek could really rip the way it wants to, it would just naturally be forming and re-forming red-legged frog habitat indefinitely,” Westphal says, allowing frogs to perpetually “stay ahead of newt predation.”

Westphal is also working with amphibian experts from Cal Poly Humboldt to design the array of new ponds above Molino Creek. In each of the ponds, he and his colleagues plan to place either red-legged frog eggs (salvaged from nearby ponds that are at risk of drying out), rough-skinned newt eggs, or a mix of both. After a year’s worth of breeding and eating, the newts and frogs that remain will be counted by researchers and the data used to prioritize habitat restoration. “If we see significant frog reproduction in ponds with an absence of newts, it would vindicate this type of pond as the thing we want to do, at least in [the] short term,” Westphal says. As a bonus, the frogs that survive could be relocated to areas where drought or predation has taken a particular toll on the species. “These ponds should pump out a ton of frogs,” he says. “Not to be a total capitalist about it.”

It could be months or years

Much of this research and restoration will proceed out of the public eye, since the BLM’s plan for Cotoni-Coast Dairies bars public access to about half of the land. The agency divides the property into four zones, and all planned trails and parking are contained within two of these zones. Plans for the northernmost zone include a new parking lot and nine miles of hiking and mountain bike trails within the Molino and Agua Puerca Creek watersheds. Farther south, a trailhead near Yellow Bank Creek will lead to ten miles for hikers and equestrians.

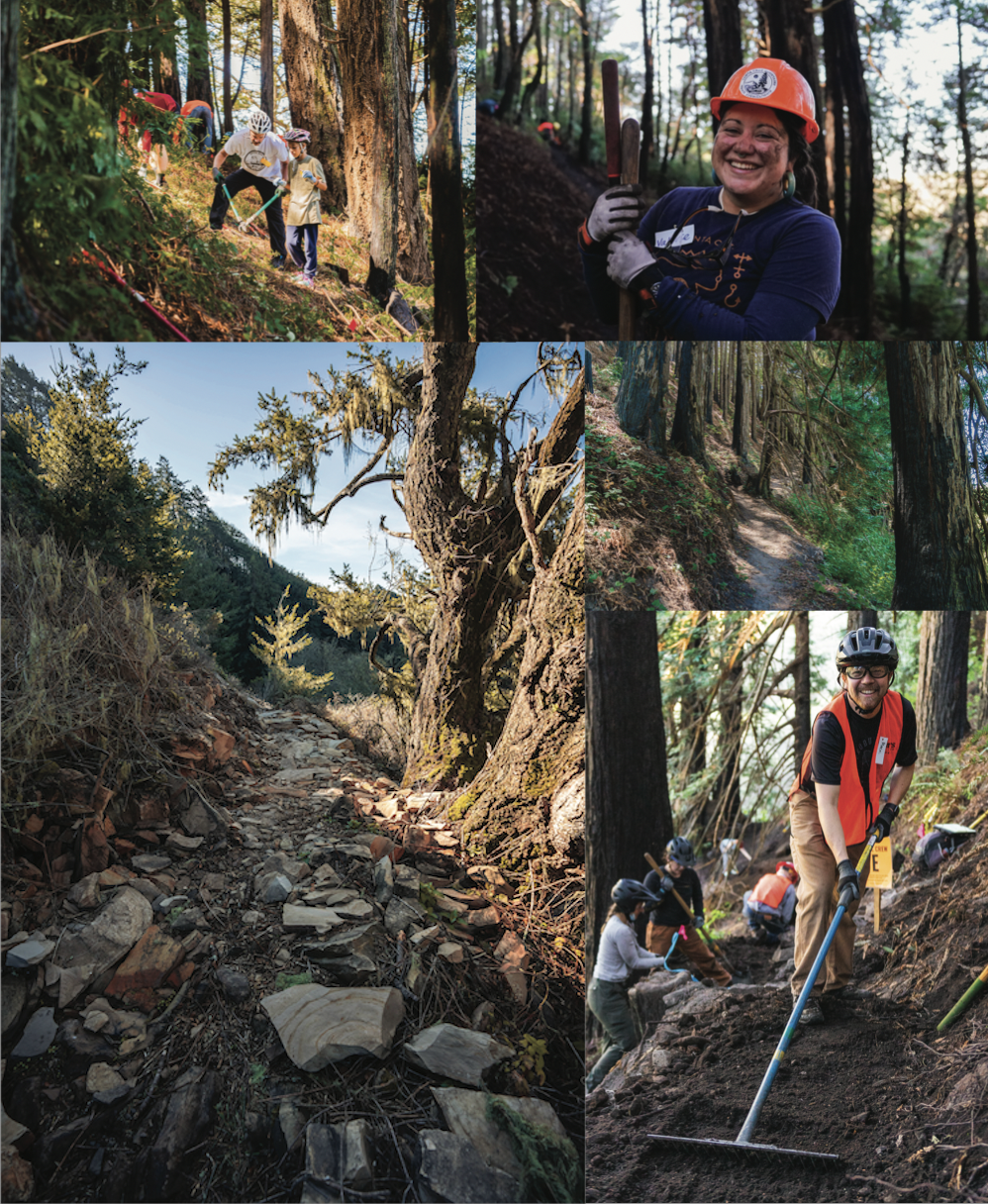

“This project is unique in that we’re starting with a blank slate for a new trail network … A lot of our local trail networks were inherited farm roads or logging roads,” says Matt De Young. He’s executive director of Santa Cruz Mountains Trail Stewardship, a nonprofit that’s raising funds and recruiting volunteers to help build new trails at Cotoni-Coast Dairies. The trail network will offer a range of challenges and vistas, from strolls over coastal terraces with views of the coast to single-track twisting through steep valleys in the monument’s upper reaches.

The public zones encompass areas with more preexisting development and infrastructure, says BLM planner Sky Murphy. The other two zones contain more habitat for sensitive species, archaeological sites, or safety hazards from mining and quarrying. “That’s where management is geared toward restoration and protection of cultural and biological values … We’re basically telling people they can’t enter [those watersheds],” Murphy says.

The steep topography and unusual concentration of perennial streams contribute to the impressive biodiversity of Cotoni-Coast Dairies. Redwood and Douglas fir forests grow on the property’s steep upper slopes, giving way to stands of coast live oak, coastal scrub, and a mix of native and introduced grassland species on the mellow, sunny terraces that step down toward the coast. Red alders and arroyo willows shade the streams, which harbor critical habitat for steelhead trout and coho salmon. Mountain lions, black-tailed mule deer, bobcats, gray foxes, and badgers are among the bigger mammals found on the land. Hermit thrushes and Wilson’s warblers hang out along the streams, and red-tailed hawks, northern harriers, and great horned owls hunt in the forests and grasslands.

At least superficially, locals and the BLM are aligned on the land’s ecological significance. But when it comes to the details of balancing preservation, parking, and traffic, the agency and a host of local groups have struggled to agree.

The watchdog group Friends of the North Coast was “not excited” about the prospect of Cotoni-Coast Dairies becoming a national monument in the first place, says the group’s president, Jonathan Wittwer. They believed that the protections placed on the property when TPL transferred the land to the BLM in 2014—which barred mining, logging, and motor vehicles—were plenty strong. And they were skeptical of promises of federal funding to help local first responders handle any incidents that might ensue from an estimated 300,000 annual monument visitors. Wittwer’s group pushed for conditions written into the monument designation that would guarantee such funding, “but those conditions have never been honored,” he says.

Aside from headaches for residents of Davenport and Bonny Doon, Wittwer worries how the anticipated influx of people could affect wildlife, including the mountain lions that currently roam the land. His concerns on that score are shared by Chris Wilmers, the cougar expert who leads the Santa Cruz Puma Project, a partnership between UCSC and CDFW. The BLM’s plan situated the southern parking lot in an area that Wilmers has pointed out would indirectly interfere with mountain lion habitat. Ultimately the agency had to abandon its plans for the southern entrance when it lost permission to build through a private property adjacent to the lot.

“We will still have trails and visitation on the southern portion of the property, but we’re still navigating this sticking point,” Murphy acknowledges. He says visitor access to the southern part of the monument might not come until 2026 or later.

The fate of the northern parking lot, meanwhile, is pending a second pass at the environmental review process. The U.S. Department of the Interior’s Interior Board of Land Appeals found deficiencies in the BLM’s first review, and neighbors have raised concerns over whether the proposed lot location threatens habitat for monarch butterflies and creates a traffic hazard. A decision might come this summer, but Murphy says it’s unlikely the BLM could build the lot before next winter’s rainstorms shut down construction season. It’s slim odds that any part of Cotoni-Coast Dairies will open before summer 2024.

Wittwer, whose group has filed no small number of appeals, lawsuits, and objections to various proposals for Cotoni-Coast Dairies in the past 25 years, says that he and his allies are not trying to keep the national monument locked up indefinitely. “We have been trying to find a way to open the monument from the get-go and telling the BLM, ‘Here’s how we think you should do it.’”

On our tour of amphibian hot spots around Cotoni-Coast Dairies, Westphal and I drive through a lot of locked gates. He hands me his key ring, and I hop out and scan through a daisy chain of padlocks, each labeled with the initials of a different entity with an interest in and history on the land—utilities, timber companies, farmers, the cement plant—until I find the one labeled “BLM.”

“If there’s one thing you take away from this visit, it’s that this is a pretty complicated place,” Westphal says. “Now it’s our job to wind through the interstices of all these disparate interests and make some conservation happen.”