On the southwestern end of Richmond’s Miller/Knox Regional Shoreline, around the corner from throngs of yachts, is a very large problem pier.

“The Ferry Point Pier is in imminent danger of collapse,” wrote Edward Willis, a planner for the East Bay Regional Parks, which has owned the 125-year-old pier since 1991, in 2022. “Any significant weather event could cause a significant collapse and failure of the pier.” Large chunks could fall off, or the structure may collapse entirely, leaving free floating wood pieces in the Bay to clog up routes for commercial shippers and recreational kayakers alike.

Now, thanks to $1.2 million in federal funds from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, officials at East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD) hope to get the old Ferry Point pier out of the water before something terrible happens. Beyond the safety hazard, these old logs were long ago treated with creosote, a preservative that is toxic to aquatic life. So, beginning later this summer or fall, over a thousand 12- to 14-inch timber piles will be removed. In doing so, EBRPD will restore approximately 800 square feet of underwater habitat—a prime location for eelgrass beds and spawning Pacific herring. (A concrete section of the pier, where recreational anglers can fish without a license, will remain.)

About this project: Bay Nature is reporting on funding for nature in BIL and IRA. Tell us what you think or send us a tip at wildbillions@baynature.org, and read more at our Wild Billions project page.

“We’re pivoting this from a navigation hazard to an environmental restoration project,” says Becky Tuden, environmental services manager at EBRPD. The project is expected to take a month or two. It’s been funded as a restoration project by the Environmental Protection Agency’s San Francisco Bay Water Quality Improvement Fund. “It’s pretty exciting to be able to do something for the Bay,” Tuden adds.

The project, first announced in 2022, has been much delayed. And the pier breaking apart is a real danger—it’s already happened twice recently. In January 2021, a worn-down portion of the pier collapsed, requiring the parks district to remove a hundred feet or so under an emergency contract. Six months later, the same thing happened again, with an even larger piece of the pier.

Willis, the EBRPD planner, says the breakages made them see the pier as “an immediate hazard” for nearby channels. “We certainly don’t want to see a shipping accident because of pieces of this pier coming off.”

A history of neglect

The pier was originally built in 1900. Back then, a transcontinental railway operated by Santa Fe Railroad brought passengers and cargo to Richmond, its southwestern terminal at the time. From this pier they would load onto vessels heading to San Francisco and other parts of the Bay.

But bridges were built, and ships were forgotten. Passenger rail ceased in 1933. All freight and barge traffic stopped by 1975. After that, the pier was neglected. The East Bay Regional Park District acquired it in 1991. Today, wild grass has reclaimed wooden tracks that lead to nowhere, and one segment of rail hangs perilously from the gantry, dipping its rusty toes into the water. People walking in the nearby Miller/Knox Shoreline park described it as a popular hangout spot for local residents, along with the public fishing pier. “Not everyone has a backyard or a deck to barbecue,” says Barbara Arkin, a longtime resident. “I think it should have been preserved,” says resident Annie Meyer of the historic old pier. “But it’s too late now. We’ve reached a point of no return.”

That isn’t practical, park officials say. After a half-century of neglect, about 70 percent of the creosote-treated wood is too degraded to repair. For the parts that could be fixed, officials say doing so would cause a $1.2 million project balloon to $5.5 million, and the repaired segments would still only last 20 years anyway. (The historic gantry—a metal framing that was once above a platform for railroad tracks—will be preserved.)

“While it is removing a historic structure, it’s really to improve public and commercial safety,” says Willis. “As well as improve habitat for a variety of species that call San Francisco Bay their home.”

Let there be light (for the eelgrass)

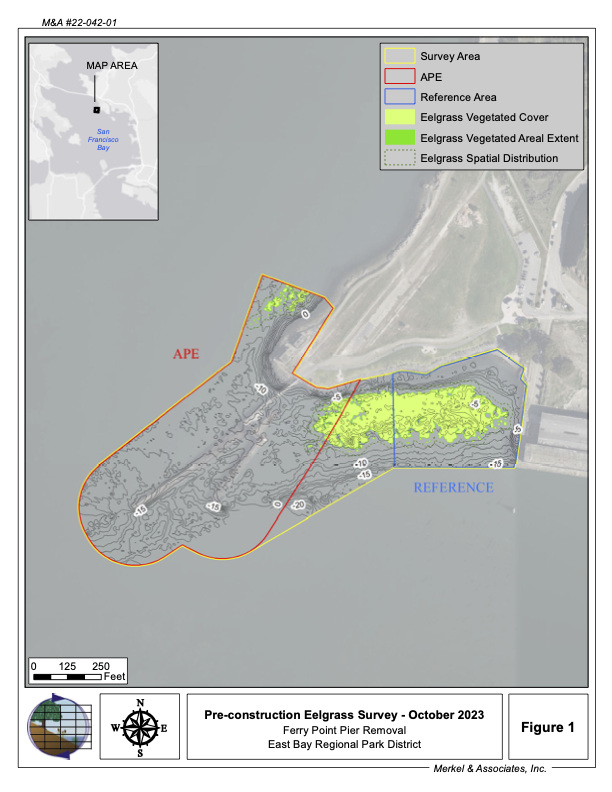

The first thing that will return to the water once the pier is removed is possibly the most important—light itself. About 16,000 square feet of overhead dock will be pulled out of the water, revealing what park officials hope is prime real estate for eelgrass to move in from nearby.

“It’s a foundational habitat,” says Brook Vinnedge, ecological services coordinator at East Bay Regional Parks District. “It sustains life for so many other species.” Eelgrass beds are nurseries and refuges for all sorts of fish and invertebrates. Pacific herring, in particular, use them as spawning beds—and in turn feed many other fish and birds.

Protecting existing eelgrass will be a priority during the demolition, which will be carried out entirely by barge. EBRPD officials plan on using turbidity curtains—long underwater stretches of polyester—to keep debris and dust away from sensitive eelgrass beds.

Funding for the project also covers eelgrass monitoring, which park officials say will go on for at least a year after demolition barges have left the waters.

A long time coming

The removal project has already suffered two major delays. In 2022, while EBRPD was wrestling with the preservation requirements for historic sites, the agency missed the “salmon window”—the golden period between June and November when projects like this can occur without encroaching on the movement of anadromous fish. In 2023, when things seemed lined up and ready for the fall, their contractors discovered a black, resin-like stain on the pier’s surface—asbestos, mixed in with tar.

“It was probably there as a fire retardant,” Willis says. “It’s a big wooden pier and asbestos was used for many, many decades for fire suppression.”

That was an unusual find. But creosote treatment was standard for piers at the time; it kept wood from rotting in the water. Now it’s considered a “forever chemical” that wouldn’t be used to make any modern pier, and removing it is a high priority for EBRPD and other organizations trying to restore our shorelines. In 2020, the Coastal Conservancy awarded over $3.2 million in grants aimed at removing dilapidated piers across the state.

“For all these 100-year-old piers throughout the Bay, these pilings, there’s a significant movement to get those out of the water,” Vinnedge says.