I called Joey Santore just as he’d returned from a botanizing trip to South Africa. “I’m stuffing envelopes right now,” he told me from his home in West Oakland. “Mailing out stickers. It’s a big part of how I make my money.”

Santore has hundreds of thousands of followers online, but not for the quality of his beautifully hand-drawn stickers picturing black-and-white flowers, which he sells online. He’s known for Crime Pays But Botany Doesn’t, a self-described lowbrow approach to plant ecology, which takes him everywhere from Oakland rail yards to New Caledonia, ranting about plants, trains, liberals, and conservatives, but mainly plants. His expletive-filled videos and podcast episodes are some of the most popular botany-related shows in the English-speaking world.

Santore is not a botanist by training. He grew up in the Chicago area, then moved to the Bay in 2000. He went to college for two years “for sociology or something,” before dropping out. For most of his adult life he’s worked on freight trains. Before that, he was riding them illegally, which fostered an early love for geology and plants. When he speaks, it’s with a distinctly nonacademic Chicago accent (which he often hams up) that allows him to touch every rung of the social ladder at once.

“I just realized I didn’t know anything, and I just had this desire to learn,” he says about his early years. “I didn’t want to be an ignorant f–k my whole life, taking everything for granted and letting people tell me how the world worked. I wanted to look it up for myself.”

Part of his passion comes from seeing plants in their native habitat, which was one of his main takeaways from his trip to South Africa. “There’s a lot of plants there that I previously had come to hate, just because they’ve been used in California horticulture and so out of context,” he says. “But seeing them in habitat, I gained a totally new appreciation for them, everything from some of the pelargoniums, the weird geraniums, to some of the cool members of Asteraceae that are down there.”

In that spirit, I’d called him not to talk about far-flung regions of the world but about home. What, in the opinion of Joey Santore, is one of the most rewarding plants to witness in habitat in the Bay Area?

Fritillaria falcata

“Because of the way serpentine rock weathers, it crumbles into these cubic, marble- to golf-ball-sized pieces of talus,” he tells me. “You get these mountains that are made of serpentine that have been uplifted, and because of how it weathers, it fractures into the angularity and size of these talus slopes. There’s no soil. There’s just this rock. And then there’s just these cobbles, these serpentine pebbles. And then they kind of break down, and you get something maybe resembling a soil beneath them.”

On those talus slopes grows the talus fritillary, known as Fritillaria falcata. Santore first saw the Coast Ranges endemic in 2018. It virtually never grows on flat ground and lives on serpentine rock, which, with high levels of magnesium and iron and low levels of nitrogen and calcium, makes for notoriously harsh growing conditions. It’s also very small, only 2 to 8 inches tall. “It’s not a plant you’re going to stumble across, really,” he says. He was looking for it specifically. Since then, he’s visited and revisited various populations probably a dozen times, he estimates.

The flower of the talus fritillary resembles that of California’s common checker lily, with mottled rust-red, green, and yellow tepals (essentially petals), but a few morphological differences make it sleeker. Its anthers are a supple red, and the flower itself often stands erect, instead of nodding downward like most fritillaries. Lastly, its leaves, often the only sign of the plant in dry years, are sickle-shaped and a pale blue, waxy hue. “Without serpentine, ultramafic soils, and the uplift that caused them to weather into these talus slopes at the base of these cliffs, you wouldn’t have this plant. So it’s evolved specifically for this habitat; it’s remarkable.”

According to the California Native Plant Society, the talus fritillary has two disjunct populations, one in the hills south of Livermore and one around San Benito Mountain. Santore says there’s a population around Monterey in herbarium collections, but no one to his knowledge has seen it in a long time.

“One of the populations is on private land,” he says. “It’s some guy in eastern Alameda County, and he’s got cattle out there. And we went there and the cattle had walked up the slope. You step on this stuff and it starts to move, starts to roll down. It’s like stepping on a pile of sand, basically. So you can imagine what a 1,500-pound cow would do. That could easily be wiped out just by one guy’s bad decisions. I mean, he doesn’t give a s–t. I’m sure he’s like some Trumper. Maybe he’s even the kind of person that just to spite the libs would go full—I don’t know. Purely hypothetical, but…”

Inarticulate eloquence

The inviting paradox of Joey Santore is his inarticulate eloquence. When he interviews guests on his podcast, his questions are often rambling. He sometimes pauses awkwardly, sometimes talks over his guest. Yet he speaks on a vast range of plant topics, from the selection pressures on a single rare buckwheat species to the geologic rise of flowering plants, with an inspiring tone of awe and authority.

Santore’s vantage from outside academia allows him to approach plant ecology with a mixture of hard evolutionary science and an unhinged form of humor and wonder (you will find it hard not to start calling Italian cypresses “butt plug trees”). That in turn has landed him interviews with botanical giants such as Dr. Peter Raven of Missouri Botanical Garden fame.

“For me it’s always been fun because I don’t have a reputation to lose,” Santore says. “I don’t have academics to please. I don’t have people I’m relying on to give me grants to do my research. I just go out there and I look at plants and I make it fun. I mean, that’s the happiest I ever feel is being out in these places, looking at these life-forms that’ve been there for millions of years.”

To get a traditional academic’s take on Santore, I talked to Chris Pires, dean of the International Plant Science Center and chief science officer at the New York Botanical Garden. Two hundred thousand YouTube subscribers, after all, does not guarantee scientific accuracy. Pires appeared on Santore’s podcast in September 2021 to talk about monocot taxonomy.

“It’s like engaging with an MC Hammer on Twitter, or something,” Pires says. “Of course they’re not an expert with PhD training and specialist knowledge. But if they’re interested in science and bring a new group of people to the table, that to me is exciting. So that’s the spirit that I appreciate in Joey, even if his style is not for some people. That’s fine. There’s other people out there for them.” (Note: Santore is more of a plant expert than nearly all celebrities. No shade on MC Hammer.)

Santore’s influence on a younger generation is palpable. JoeJoe Clark is a park steward assistant aide at Napa County Regional Park & Open Space District and a restoration technician at Sonoma Ecology Center. Clark works every week with state park visitors, trying to translate nature for the urban mindset. “One thing about Joey is that he’s a straight shooter,” Clark says. “He’s just no-filter. If people definitely who are in the role of science kind of have a shell, he breaks it. He doesn’t have any protocol. He’s more of a Family Guy character. I’m more of a Disney character, but we get to the same conclusion.”

For Mitch Van Dyke, a 25-year-old seasonal biological science technician for the US Forest Service’s PacFish/InFish Biological Opinion Monitoring Program in Logan, Utah, Santore’s videos have helped determine a career path. After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in marine biology, he applied for a wide array of water- and plant-related seasonal jobs. Over the winter, as he waited for responses, he discovered Crime Pays, watching Santore’s videos almost every day.

“It made me 200 times more curious,” he says. Santore inspired him to download books from the file-sharing website Library Genesis and to make flash cards to learn plant family characteristics. “I think it helped make me surer that I wanted to move toward plants and more excited to explore it on my own, just wander around and take pictures of everything. And it spurred an obsession with iNaturalist as well, just as a place to collect all my photos.” When application season came to a close, Van Dyke chose his present Forest Service job, which has him roaming around streams in the Intermountain West and identifying plants 40 hours a week.

“A lot of times I’ll watch them [videos] while I’m going to sleep, and he kind of lulls me to sleep. If I can’t fall asleep, then I get to watch kind of an interesting video, I guess. I wouldn’t recommend it if you have sleeping issues. There are a lot more soothing voices.”

Mandela Parkway

The first time I ever met Joey Santore, he asked me to meet him near his home at the time in West Oakland in the spring of 2021. As I stood on Mandela Parkway, it struck me that the landscaping was obscenely intricate for a West Oakland city block. When Santore arrived 15 minutes later, I was absorbed in a festival of forbs, shrubs, and small trees. I noticed he was wearing leather gloves, and after saying hello, he got down and started weeding, traffic whirring by on either side of the median.

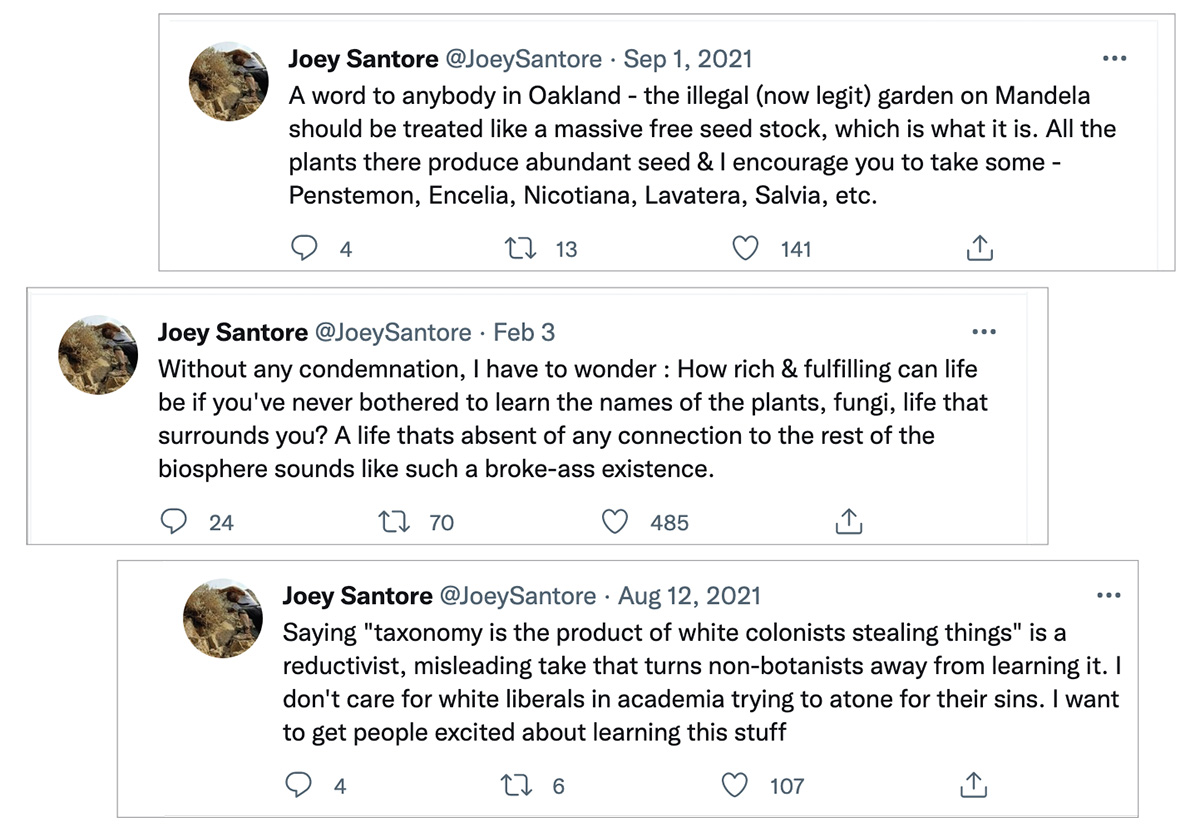

Over the past several years, it turns out, Santore has guerrilla-

planted the parkway. About four city blocks are heavily planted, but his work can be seen all along the mile-long stretch from 12th to 34th Street. The long stretch of median is a mixture of native plants and Mexican cloud forest plants that are able to thrive in the Pacific air of the Bay Area. He’s wanted to try growing Fritillaria falcata, but hasn’t been able to collect seed from it.

“If this was a restoration effort, I’d be planting all native stuff,” he says. “But it’s not. It’s the site of a former double-decker freeway where people still dump used needles and human s–t.”

Santore doesn’t drive freight trains anymore. He makes enough money from Crime Pays But Botany Doesn’t to travel around and look at plants full time. With recent episodes on the island of Hispaniola, and in Shasta County, West Texas, eastern Montana, and the Dakotas, and South Africa, it’s hard to wrap one’s brain around when Santore rests. When I left him, he was still weeding a rhizomatous Peruvian nightshade off his strip on Mandela, about a block from where we started.