Explore The Ridge

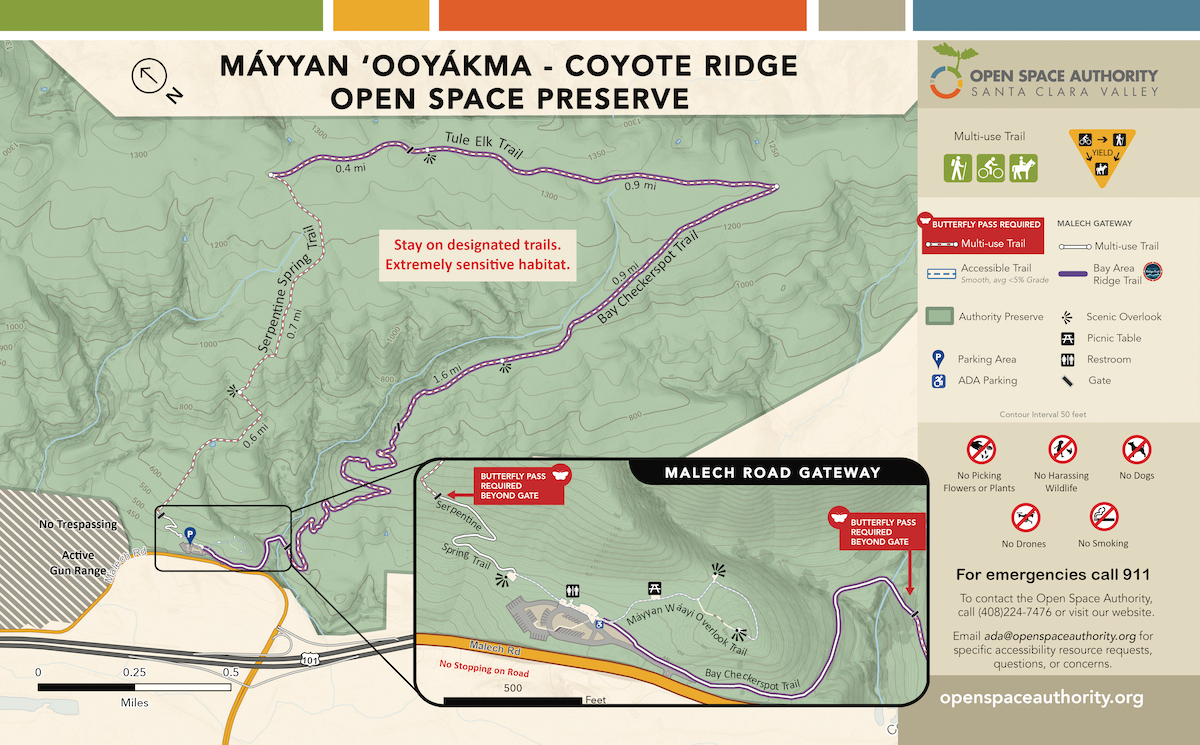

» Getting there: The parking lot, bathroom, trailheads, and interpretive signage are at 9611 Malech Road, just off Highway 101. To access the preserve by bicycle, use the Coyote Creek trail from San José to the north and Morgan Hill to the south, or travel along Santa Teresa/Hale and take Bailey Road to Malech.

» Special hours: Before you visit Coyote Ridge, check the Open Space Authority website’s “Know Before You Go” flyer for current hours, which vary according to butterflies’ and other wildlife’s seasonal needs. Link Here.

» Ancestral lands: Máyyan ‘Ooyákma means Coyote Ridge in Chochenyo, the language of the Muwekma Ohlone. The Open Space Authority collaborated with the Muwekma to create interpretive signs that include Chochenyo translations and explanations about ancestral land use and current tribal conservation and stewardship.

» Trails and Accessibility: Coyote Ridge has a quarter-mile ADA-accessible trail made of decomposed granite starting at the parking lot, with access to views, interpretive signs, and a picnic area.

» Butterfly pass: Read the preserve’s guidelines and agree to follow the rules to get a Butterfly Pass, which you must have with you to access the Habitat Protection Area. You can obtain a pass via QR codes, found throughout the preserve and parking lot, or the Open Space Authority website. Staff and volunteers can assist those on site without access to a computer or smartphone.

» Wildflower tours: During peak wildflower and butterfly breeding season in March, April, and May, visitors are required to make reservations for docent-led wildflower and butterfly tours at the preserve.

At the recently opened Máyyan ‘Ooyákma–Coyote Ridge Open Space Preserve, golden serpentine grasslands, dotted with boulders, plummet over a thousand feet into Coyote Valley. Sweeping views of the Santa Cruz Mountains lie to the west with downtown San José to the north. In spring, the grasslands erupt with wildflowers, including California poppies, lupines, mariposa lilies, goldfields, tidy tips, the rare Mount Hamilton thistle, and more. The federally threatened bay checkerspot butterfly, its wings flecked with orange, white, and black, flits and darts among the flowers.

“This is one of the biodiversity hot spots of the South Bay, a crown jewel,” says Lucas Shellhammer, planning manager for the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority.

Just off Highway 101 and only 10 miles southeast of the heart of San José, the preserve protects the largest continuous serpentine grassland in the southern Bay Area and, in all, is home to 13 threatened and endangered species. There is also a meandering herd of tule elk, deer, coyotes, raptors, mountain lions, and bobcats. A steep, five-mile loop trail traverses the preserve’s more than 1,800 acres, and unique among Diablo foothills preserves, Coyote Ridge will experiment with balancing sensitive ecological conservation with public recreation.

“We’re trying to showcase a preserve where recreation and really sensitive species can coexist in a way that benefits from having them both on that site,” says Derek Neumann, field operations manager for the Open Space Authority.

Coyote Ridge is known as the gateway to the Diablo Range in the east, creating a corridor for wildlife, such as mountain lions and bobcats, traveling between the Santa Cruz Mountains and the other range. That connectivity helps ensure genetic diversity in local populations. “Having this block of open space is really critical to allowing the animals the sense of security they need,” says Neumann.

The ‘mother lode’ for serpentine habitat

The Bay Area’s tectonic shenanigans and diverse geology underlie the biological diversity blooming at the surface, including Coyote Ridge’s dazzling display of rare and endangered serpentine wildflowers. Serpentine rock, known as serpentinite, is seldom seen at the earth’s surface—except along tectonic plate boundaries. Under pressure, as the Pacific plate slipped under the North American plate, serpentine rose up from the earth’s mantle miles below the surface, exposed in outcroppings and boulder fields throughout Northern California.

“That faulting is taking the serpentine that’s deep underground, where the subduction zone was, and lifting it up through the landscape,” says Neumann.

Serpentine soils make up only about one percent of California’s soils. The iconic California state rock—named for its mottled, snakeskin-like greenish blue hue—speckles the steep slopes and windy hilltops of Coyote Ridge as lichen-encrusted boulders. “Coyote Ridge is the mother lode for serpentine habitat,” says Andrea Mackenzie, general manager of the Open Space Authority.

Serpentine grassland is defined by its inhospitable soil chemistry, which drives biodiversity as local species specialize in order to survive. Serpentine soil lacks significant levels of nutrients essential for plant growth, such as nitrogen, potassium, and calcium, and at the same time contains potentially harmful substances such as asbestos (one type of asbestos is itself a fibrous form of serpentine) and high levels of heavy metals, including magnesium, chromium, and nickel.

This double whammy of harsh conditions results in rare, endemic species—species found within a specific habitat and geography and nowhere else on earth. More than 28 species of plants and animals live only in serpentine soils. Nestled in the nooks of serpentine boulders, the endangered Santa Clara Valley dudleya (Dudleya abramsii ssp. setchellii) flourishes. Nearby, the dwarf plantain (Plantago erecta) hosts the bay checkerspot butterfly caterpillar, and the federally listed Metcalf Canyon jewelflower (Streptanthus glandulosus ssp. albidus) basks in the sun.

Saving the serpentine

Highways. Interchanges. Tech campuses. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Santa Clara County was developing rapidly, which spurred U.S. Fish and Wildlife to require a habitat conservation plan for the grasslands surrounding proposed projects. Decades of research by conservation biologist Stuart “Stu” Weiss found that cars traveling along Highways 101 and 85, which converge just northwest of Coyote Ridge’s slopes, cough up nitrogen in their exhaust, impacting the area.

The nitrogen settles on nearby grassland, essentially adding fertilizer to the nutrient-poor landscape and enticing nonnative plants to creep in, crowding out the local serpentine specialists. Of particular concern are plants like the dwarf plantain, which the bay checkerspot depends on. If nitrogen deposits from roads and the nearby Metcalf power plant increased, dwarf plantain and other rare serpentine natives could be overtaken by nitrogen-boosted invasives, and the checkerspots could dwindle.

“This was just an unbelievably important discovery,” says Mackenzie.

Research by Weiss and others helped make a case for preserving serpentine grassland habitat and requiring industries that release nitrogen in the area to take steps to mitigate effects of such development, often by funding conservation efforts. Weiss’s same research eventually also informed the practice of conservation grazing. Cattle are periodically brought out to the grassland, where they prefer to munch on nonnative species, minimizing competition and giving native serpentine species a chance to grow.

From the Cold War to conservation

From 1959 to 2004, residents in Santa Clara Valley were rocked by the occasional sonic boom. For 45 years before becoming a preserve, Coyote Ridge acted as buffer land for a 5,000-acre Cold War–era rocket and missile propulsion testing facility in the next valley over, on the eastern side of Coyote Ridge. There, United Technologies Corporation (UTC) developed rocket and missile propulsion systems.

In 2015, the Open Space Authority acquired Coyote Ridge from UTC in a unique tax arrangement for $8.6 million. The overall design and construction of the preserve cost $4 million, with about 75 percent of the preserve’s funding coming from California State Parks and Proposition 68.

“This site can be characterized as a Cold War to conservation success story,” says Mackenzie.

Working on nature time

Coyote Ridge is not your typical open space preserve. Protecting checkerspot habitat comes first, and inviting the public to enter and recreate on such sensitive habitat while prioritizing endangered species is an experiment. A study conducted near Palo Alto found that the presence of walkers and joggers led to a loss of biodiversity and number of butterflies compared to areas with no recreation. To give checkerspots a chance to roam free before visitors arrive, Coyote Ridge will have limited seasonal hours, opening late in the winter and spring. These extra hours give the butterflies time to warm their wings, allowing them to fly away easily so as not to get trampled or otherwise disturbed by visitors.

“We’re really working on nature time,” says Shellhammer. “We’re trying to make sure that the butterflies have time to wake up, feed, and spread their wings before people come out here.”

Volunteers played a major role in making the preserve accessible to the public. A mile and a half of the Bay Checkerspot trail was painstakingly built by hand to minimize wildlife disturbance and asbestos dust, with a total of 600 hours contributed by more than 66 volunteers. Going forward, volunteer docents and trail masters with the Open Space Authority will continue to be essential in operating the preserve.

“Everybody who comes out here is going to be a part of protecting and respecting this place and all the wildlife here,” says Charlotte Graham, spokesperson for the Open Space Authority.