The term “nature-based solutions” has burst outside of the bubble of ecology and conservation and entered into the mainstream policy-making conversation, it seems. Late last year, the Biden administration unveiled an NBS roadmap with an intent to “unlock the full potential of nature-based solutions to address climate change, nature loss, and inequity.” California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s 30×30 executive order last year committed California to developing more nature-based solutions. And—among other funds—the California Natural Resources Agency has a $101 million Tribal Nature-Based Solutions Program.

But what is a nature-based solution? And what is it solving?

Where did it come from?

Nature-based solutions are ways we can use nature to solve some of our biggest societal challenges—like climate-change-driven disasters, sea-level rise, the biodiversity crisis, drought and extreme heat. The term is replacing others (green infrastructure, ecosystem-based management, nature-based shorelines and systems approaches, to name a few), in part because it manages to encapsulate not just the projects themselves, but the philosophy it represents.

“It represents a fundamental shift in the way we think about the work that we do for climate change and climate resilience,” says Heidi Nutters, climate resilience lead at the San Francisco Estuary Partnership, a collaboration of various agencies and individuals dedicated to restoring and protecting the Bay.

About this project: Bay Nature is reporting on funding for nature in BIL and IRA. Tell us what you think or send us a tip at wildbillions@baynature.org, and read more at our Wild Billions project page.

When societal problems compound each other—such as droughts and wildfires, or groundwater recharge and sea level rise—the solutions, too, need to be comprehensive. Here are some examples:

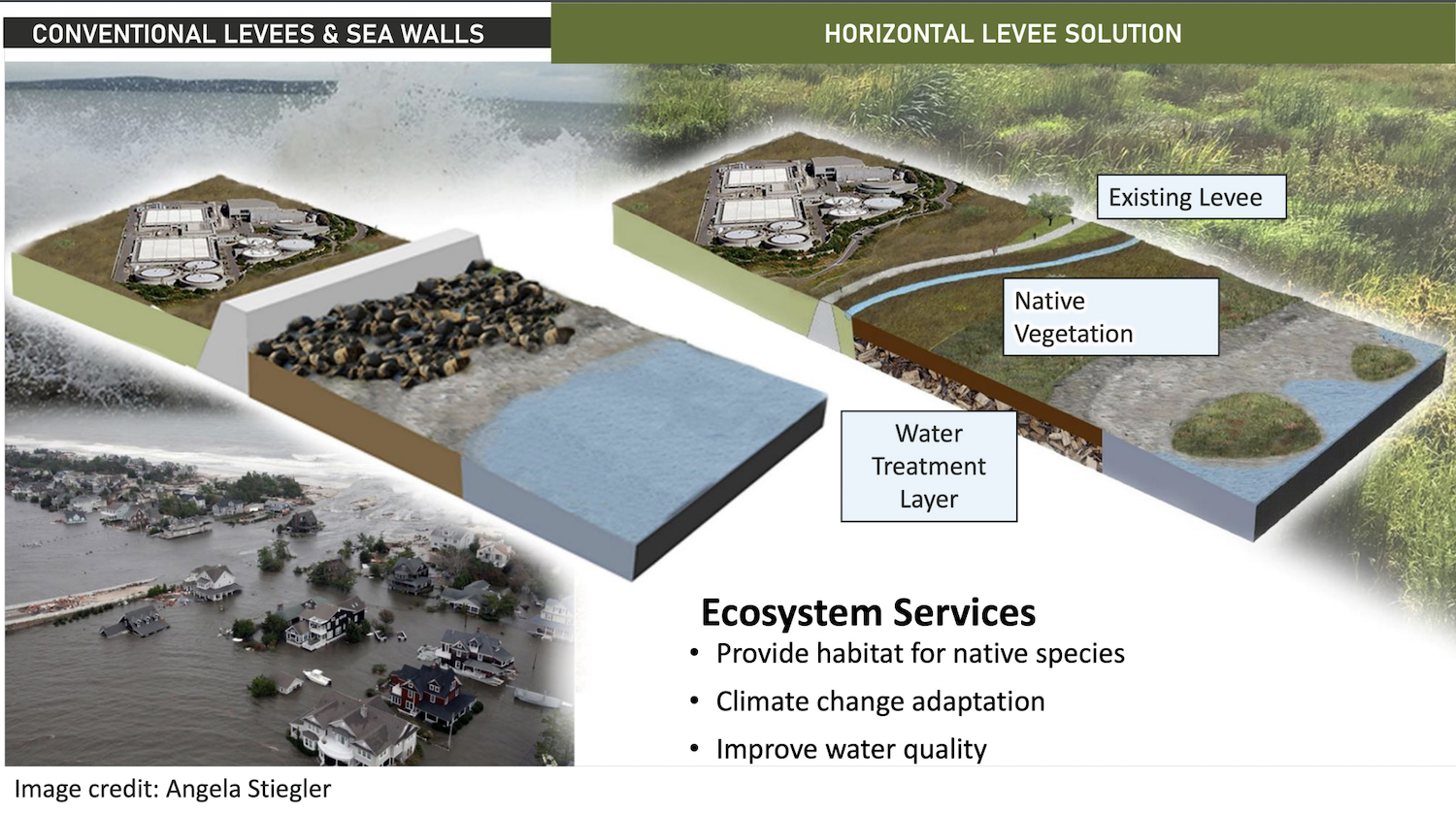

- Horizontal levees—gently sloping stretches of land, gravel and grasses that lead into the water at shorelines—can be built to protect uplands from flooding protection, provide habitat, and perhaps keep pollutants in treated wastewater from reaching waterways. These can supplement, or even replace, seawalls and other traditional stormwater infrastructure.

- Reintroducing fire into forests, to prevent more catastrophic fires and make forests healthier, instead of focusing just on suppressing fires.

- Restoring seagrass and coral to the oceans not only builds marine ecosystems, but naturally sequesters carbon, so we don’t have to rely on carbon reduction strategies.

- Urban forestry is another nature-based solution, ameliorating urban heat while providing habitat for birds and pollinators.

- Permeable pavements and bioretention basins—which are sloped areas where vegetation and gravel work together to naturally filter pollutants out of stormwater runoff—improve groundwater recharge, and can stave off flooding and sea-level rise.

The approach everywhere, it seems, is to remove the problem—that is, us—and introduce more of the solution: nature.

Nutters says so-called “gray infrastructure”—the impermeable concrete pipes, dikes, and drains of irrigation, flood management and wastewater systems of our built environment, for example—are too vulnerable to sea-level rise. Wastewater stations, for one, have pumped treated water directly into the bay, bypassing soil absorption and creating a system vulnerable to overflow. Now, engineers are instead looking to mimic natural resilience through bioretention basins. “It’s self-reflection,” Nutters says. “Taking a step back and being like, ‘Wow, we have a lot to learn from the wisdom of nature.’”

Example: Little fires everywhere

For Valentin Lopez, chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, nature-based solutions are about coexisting with and stewarding the land as it is, to maintain the existing relationships between plants, animals, and their wider ecosystem. And using fire, he says, is one of the oldest ways in which people have harnessed nature to help nature (and ourselves). Burning grassland and forests, he says, helped nurture deep root systems that helped the plants thrive, helped stave off drought, and sequester carbon.

“California’s coastal prairie was developed and maintained by our ancestors. And they used fire to take care of those plants,” he says.

Fire encompasses a lot of what policy-makers say nature-based solutions should be: ecologically restorative, multi-benefit, and contributing to a highly resilient system. Darcie Luce, an environmental planner at SFEP, says using the term “nature-based solutions” is a way of referring to tribal thinking, if it were repackaged for public works agencies—like how cultural burns have become “prescribed fire.”

Why are nature-based solutions getting so much buzz?

In short, it’s because the results are coming in, and these projects appear to work.

Ten years ago, Nutters says, she got involved in a groundbreaking horizontal levee being built at Oro Loma. The idea was to challenge the “default” embankment with a longer stretch of mud, gravel, and grasses to better break waves, grow an ecosystem, and improve water quality. But it really was an experiment. It was only in 2020 that the first scientific study documenting its effectiveness was published in Water Research.

“The science, the design and engineering, the permitting of all those pathways … We’ve been working really hard on it for the last several years,” Nutters says. “It’s only now we’re starting to have results.”

Why aren’t these solutions more popular?

It’s because they are still somewhat experimental. For Luce, we’re right to be risk-averse about infrastructure. “We take it seriously. It’s about protecting communities that are right up against the shoreline,” she says. She gives the example of downtown San Francisco as place where a concrete seawall might be the safest bet but notes, with excitement, that engineers there are experimenting with “living seawalls,” underwater slabs designed for mollusks and other critters to stick to, turning a gray option green—no horizontal levee required.

The policy framework also isn’t quite there yet to unlock the full potential of nature-based solutions. At a recent wetland migration workshop in San Francisco, government officials noted how people working to help Bay Area wetlands move uphill as the sea encroaches have had some run-ins with the federal No Net Loss rule for wetlands (normally invoked for developments destroying wetlands, it requires that they “mitigate” and create some wetlands elsewhere to compensate). “When you’re doing a restoration project, it’s a little hard to wrap your mind around having to mitigate for your restoration project,” state Coastal Conservancy director Amy Hutzel remarked.

Another issue: Sometimes public access and endangered species protection, two common goals of these types of projects, can clash. Restoring wetlands along the shoreline can bring back sensitive species, like salt marsh harvest mice. But public access to the shoreline may then be limited to keep people from disturbing them.

The burden is on the engineers, Luce says. “We have to do both. We have to design smartly, in ways that create space for wildlife and also for people to interact with the shoreline.”

But are nature-based solutions really that new?

Not at all. After all, nature has been here since the beginning. Chairman Lopez says, if anything, it’s gray infrastructure that is untested science, developed with short-term goals of mitigation, and with results that are good only for five or 10 years. By pursuing what is good for nature, he says, we will be thinking of “the next seven generations.”

“Our ancestors, they were all scientists,” he says. “The indigenous knowledge that we’re talking about, that was based on science that was developed over thousands and thousands of years.”

Update, Oct. 24: This story has been updated to refer to the San Francisco Estuary Partnership as a collaborative, not a collective. A description of horizontal levees was clarified to indicate that they provide habitat, and that their wastewater pollution impacts are not yet proved.

MORE READING

Nature-based solutions in the wild

The term’s just gaining steam, but Bay Nature’s been writing about nature-based solutions for a long time. Here’s a deep dive:

- Want to Prevent California’s Katrina? Grow a Marsh These islands in the Delta aren’t really islands anymore.

- Oro Loma: Can Wastewater Save the Bay from Sea Level Rise? Profile of the area’s first horizontal levee.

- Unburying the Creek Beneath It, A School Becomes a Steward A creek daylighting project comes with a host of benefits.

- To Stave off Wildfires, California Residents Learn to Burn California needs to burn a million acres a year. Is that possible?

- Capturing Flood Water in California’s Ancient Riverbeds Paleo valleys could help our drought problems, if we can find them.

- Largest Tidal Restoration Project in California Will Make Way for Wildlife & Mitigate Floods An ambitious restoration at Lookout Slough.