Illustrations by Jane Kim.

A walk in the rain

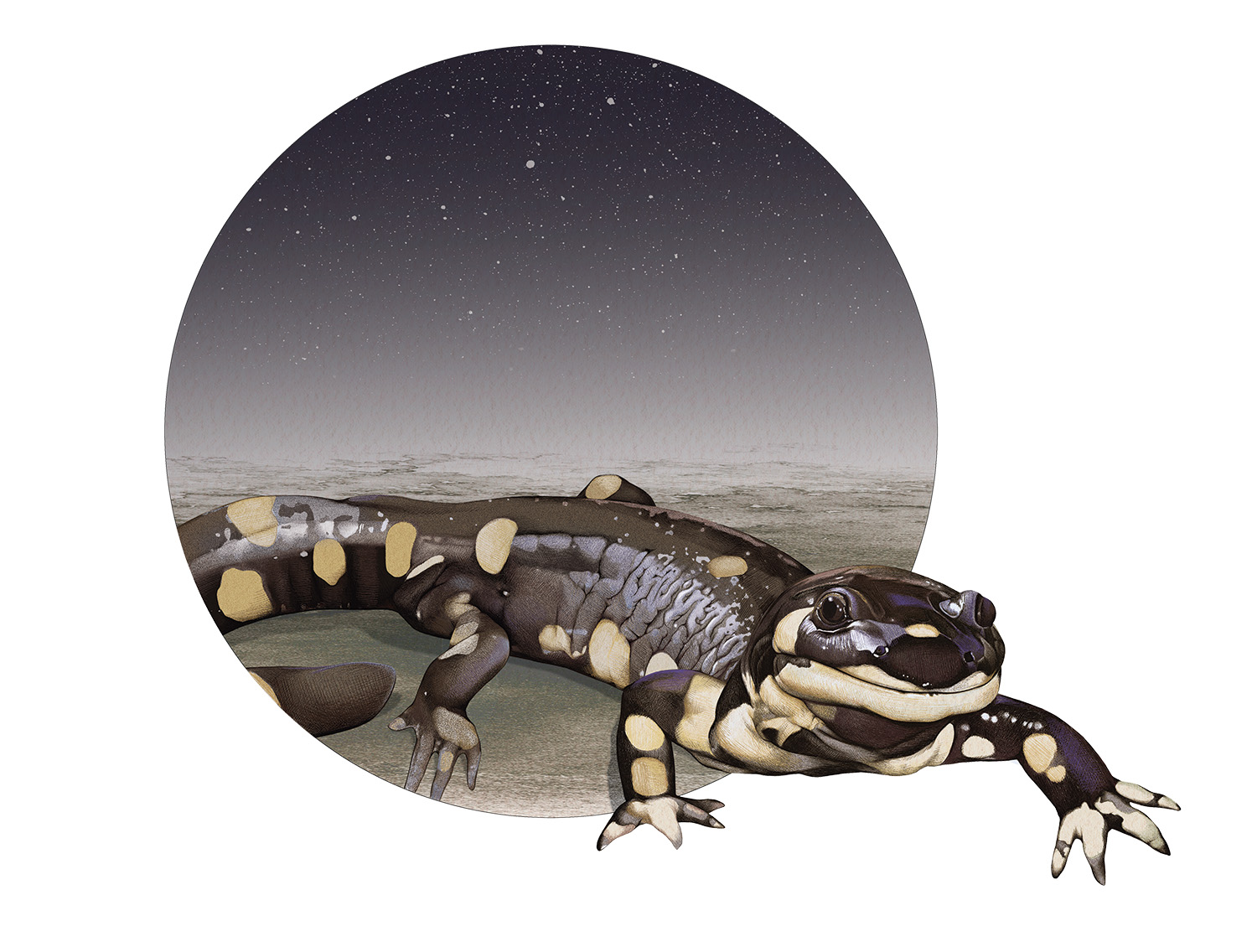

With their cheerful yellow-outlined mouths and stout snouts, California tiger salamanders (Ambystoma californiense) always seem to be smiling. Late fall rain showers awaken these gargantuan amphibians from the California ground squirrel burrows they call home. The rain tells them it’s time to find a nearby pond and spawn. Adult salamanders emerge from their hidey-holes in droves and can journey more than a mile through the night to their breeding ponds. If there are not enough rainy nights to trigger the pilgrimage, few salamanders will embark on the trek. Outside of their brief migration season, they stay tucked away and seldom seen.

Flying spiders

In the kids’ novel Charlotte’s Web, when the spiderlings spin silk parachutes and sail away, they are “ballooning.” It’s a skill used by many spiders—for example, the ground crab spider (Xysticus spp.)—to journey for food (or avoid becoming food themselves), often in the fall and spring. Depending on weather conditions, the spider may stand as if on tiptoes, then lift and shake one leg to test the wind speed, simultaneously releasing long billowing filaments of silk that will lift and carry it on the breeze. These gossamer threads will fall from the sky, leaving silvery traces over autumn.

Fish fatherhood

Starting in October, the male cabezon sculpin (Scorpaenichthys marmoratus) fertilizes and then ferociously defends a sticky mass of eggs deposited by passing females. He strays from the nest only to drive away invaders until the eggs can hatch into larvae. Cabezon larvae drift at sea for three to four months until they grow up into small silvery fish and settle in their own reefs, tidepools, and kelp forests. Camouflaged by their mottled, scaleless skin, the cabezon lurk in the shadows, ready to ambush and gobble up anything that will fit in their gaping, toothy mouths.

Snowberry feast

The common snowberry shrub (Symphoricarpos albus) knits a cozy thicket for birds, and come autumn its lush greenery fades before dropping off. The wiry branches support festive puffs of waxy white berries long into winter. Hermit and Swainson’s thrushes and robins, along with other creatures, feast on them, but the berries contain saponin, a bitter, soapy substance that can be toxic to humans.

Sharing the well

Sap wells: ever heard of them? They’re a little like watering holes, in that these pea-size shallow holes, drilled into tree bark by sapsuckers, are a draw for lots of creatures. When red-breasted sapsuckers (Sphyrapicus ruber) migrate to the Bay Area’s coast in fall, they hammer the wells in neat rows that encircle a conifer or climb it vertically. The sapsucker’s paintbrush-like tongue is adapted to lap up the sap, while invertebrates find the wells and share in the sticky sweet drink.

Hanging solo

If you happen to peer up into the branches of a redwood, fir, or pine tree—or perhaps a bay laurel or oak—and wonder, “What’s that dangling there? It looks like a lumpy pinecone,” it’s possible you’ve spied a hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus). These bats roost alone, but arrive in waves in the Bay Area each fall. No one’s sure why: the bats may be passing through during their migration, seeking a mate, or finding a comfy place to hang that’s not too cold through winter.