Snorkeling off a coral reef is nothing like snorkeling in a shallow stream on the backside of Mount Tamalpais, Eric Ettlinger says. His job is to find out how the fish in Lagunitas Creek are faring and it sends him scrambling along banks, peering into pools, bobbing on traps, wading through riffles, and snorkeling in water so shallow he gets a crick in his neck.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Mount Tamalpais: A Mountain of Stories

A Mountain of Stories was produced by Bay Nature magazine with the generous support of the Tamalpais Lands Collaborative for publication in the October-December 2017 issue of the magazine. Read more stories from the mountain:

- Meet Mount Tamalpais, by John Hart

- Nature and Culture Mix in a Theatre Among the Oaks, by Claire Peaslee

- The Nature of the Dipsea Race, by Alisa Opar

- Alice Eastwood and the Plants of Tamalpais, by John Hart

- On the Hunt for Mount Tam’s Two Known Badgers, by Mary Ellen Hannibal

- Snorkel Surveys Reveal the World of Mount Tam’s Creeks, by Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

“In lots of places I’m dragging myself along the streambed with my mask turned sideways, moving upstream so the sediment I stir up flows away behind me,” the earnest biologist says. In other words, if he looked down he’d have a mask full of silt rather than an eyeful of salmon.

Now, you might think salmon are big pink fish in need of deeper water, but the kind Ettlinger tracks are very young and still spending time in the freshwater stream of their birth. Ettlinger works for the Marin Municipal Water District, a partner in the One Tam initiative, monitoring each phase of the life cycle of endangered coho salmon and steelhead trout in their watersheds and experimenting with ways to improve fish habitat.

Over the last century, dam building, logging, and development on Mount Tam’s flanks greatly diminished what was once extensive freshwater stream habitat: creeks, pools, and rapids overhung with willow, alder, and sedges and filled with fish, frogs, and otters. These activities drove the mountain’s five major creeks into deeper and deeper channels, separated them from their natural floodplains, blocked fish migrations and sediment redistribution, and spurred erosion. Today, about 850 acres of riparian woodland and forest remain on Mount Tam, shading and buffering more than 110 miles of streams. Three major streams—Olema, Redwood, and Lagunitas—drain to the Pacific Ocean. Twenty-mile-long Lagunitas Creek has the largest watershed, and it sustains the southernmost population of wild coho salmon in the world.

Ettlinger built his first fish habitat—a pile of logs in the middle of Lagunitas Creek—15 years ago. But when he then dived under it looking for coho, his bright underwater lamp revealed the turquoise bulging eyes of an entirely different species.

When alarmed, threespine sticklebacks lift their spines, locking them in place. With a fish that rarely grows longer than three inches, this may not seem very menacing. But if you’re a big hungry trout and you eat one, you might not do it again. Those spines interfere with easy consumption.

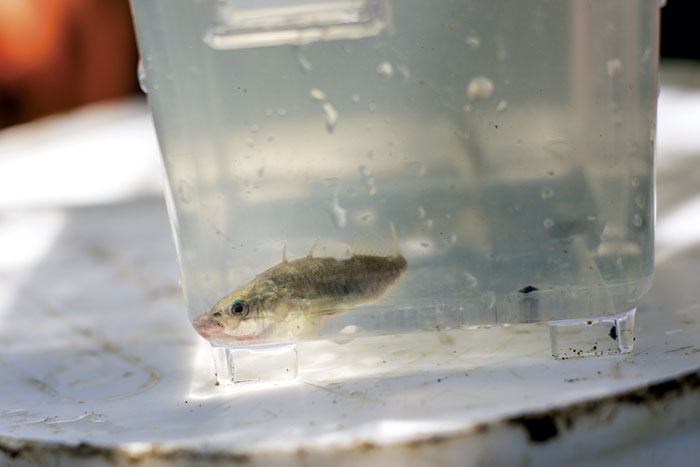

Though Ettlinger spends most of his days chasing the fast disappearing coho and steelhead, he remains fascinated by the more common stickleback. He likens this “twitchy” tiny fish—with its bug eyes, armored plates, and habit of curling into a J shape—to the charismatic sea horse.

“I still remember the first time I allowed myself to watch the sticklebacks instead of the coho. I noticed a school of all different sizes, young and old, all pointing their snouts in the same direction. When the sun hit them the reflection was so strong it was like an array of mirrors,” he recalls.

Sticklebacks are one of the most common native fish in Bay Area streams and can tolerate a wide range of water qualities; if they aren’t in a creek, that may raise an eyebrow of concern about pollution. According to the One Tam report, 22 years of monitoring show the creek’s stickleback population is in good condition while the coho’s continues to be in pretty poor, if not critical, condition. (Indeed, the water district is about to spend $1.5 million to create better habitat for overwintering coho in the lower reaches of Lagunitas.) Current salmon monitoring by Ettlinger and others includes counting redds (gravel nests) in winter, snorkel surveying in summer, electrofishing in fall (in which adding an electric current to a patch of water briefly immobilizes fish so they can be more easily examined), and trapping in spring. Much care is taken to return fish to the water unscathed.

On a spring day, I volunteered to help Ettlinger’s field crew with a phase of their annual fish monitoring cycle that hurts the knees more than the neck. A mile inland from Point Reyes Station, a break in a barbed wire fence next to a field of sweet peas and bell beans was our access point to Lagunitas Creek.

When I first saw the screw trap, bobbing violently in a rush of brown water, I wondered if I was getting too old for this kind of field reporting. The trap is a steel raft holding a spinning drum with a corkscrew funnel that guides fish into a 3- by 3-foot metal tank with a lid. Ettlinger’s field crew checks and empties the trap seven days a week for two months each spring, just as the coho and steelhead get big enough (4-6 inches) to think about heading out into the ocean.

Coho salmon, steelhead trout, and some stickleback are “anadromous” species, born in a freshwater stream or river, maturing out in the ocean, and then returning to their birthplace to spawn. While salmon and trout build redds in gravel hollows on the creek bottom, male stickleback craft their tubular nests with a combo of sand grains, plant bits, and a glue-like protein excreted from their back ends. When the male is ready to mate, his throat reddens, and he coaxes a female into the tunnel-nest where she releases her eggs. He fertilizes them, and then proceeds to court another six or seven likely ladies. He guards the egg hoard, fanning with his fins until they hatch. After that, unlike many stickleback, those in the Bay Area live out their one to two years in freshwater, while the average life cycle of coho can last three years and the steelhead’s two to four.

Stepping onto the steel platform, Ettlinger instructed me in how to use a variety of nets to scoop out branches and leaves, then fish, without squashing them against the bottom and sides. That day we netted 132 coho salmon and 24 steelhead and dumped them into orange buckets full of water and air bubbles, while sorting all other species into white buckets. That day’s selection included three sticklebacks, among others. Ettlinger clubbed a striped bass, a nonnative consumer of the species he’s trying to save.

Back on the bank in a cloud of mosquitoes, the field crew sat on bucket bottoms and measured, weighed, and identified every fish—murmuring terms like “parr” (young) or “smolt” (ready to migrate) as they documented the different life stages. The visuals are a giveaway. Spots, speckles, and pink stripes help these fish blend in with the gravelly, dappled environment of their streams. “The more silvery they get, the farther along they are in the smolting process,” says Ettlinger. The maturing process silvers spots and loosens scales, preparing them for life in the salty deep blue sea.

In all his years of monitoring, Ettlinger has only ever caught one stickleback he thought was coming back from the ocean. This particular one was “huge,” says the biologist, about the size of a bay leaf. Stickleback probably can’t grow that big without gorging on the abundant plankton of the Pacific.

Ettlinger hopes more citizens will get involved with stream monitoring, and he thinks the stickleback—with its oddball looks and spiny charisma—could be a draw. “They’re pretty tiny but easy to see from the stream bank,” he says. “Just look for something twitchy, with a shape like a sea horse, swimming backwards.”