Explore a creek

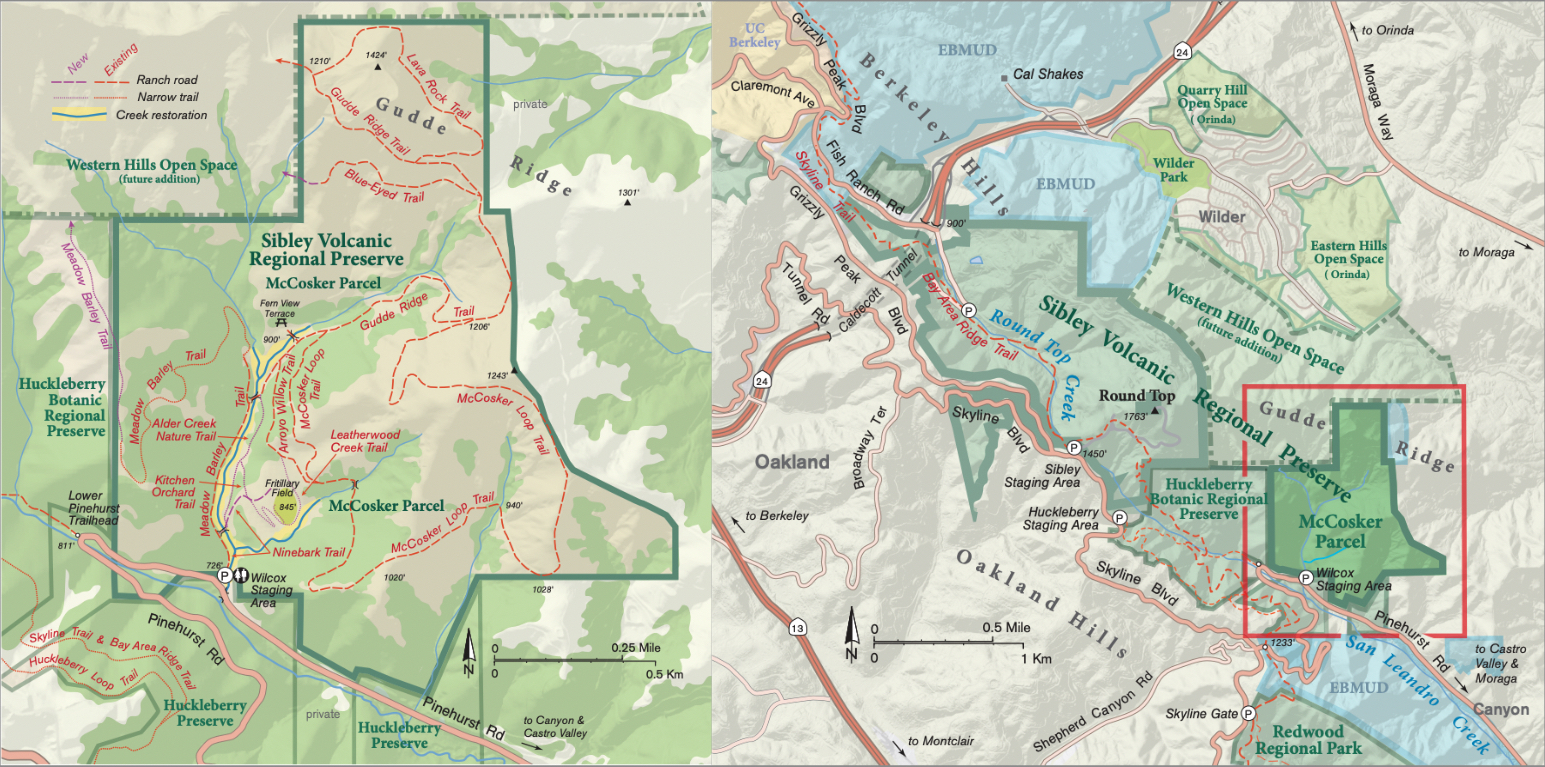

» Access the McCosker property and its five miles of trails that weave around the creeks from the Eastport Staging Area (formerly the Wilcox Staging Area) off Pinehurst Road.

» When the first phase of construction wraps up this year, the staging area will have 11 parking spaces. A future phase of construction will add vault toilets, drinking water, and additional parking elsewhere on the property.

» For more information visit East Bay Parks’ Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve page.

Matt Graul remembers his first visit to the McCosker property. It was 2010, and he and a few colleagues with the East Bay Regional Park District went to scope out this 250-acre parcel that had recently been added to Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve as part of the Gateway Valley land development deal. Graul and his colleagues parked at the property’s gate, then strolled uphill through a dry, narrow meadow, dotted here and there with outbuildings and a few crumbling foundations. Reaching a ridge, they’d paused to look back over the way they’d come when one of Graul’s colleagues raised an interesting question: “So where’s the creek?”

“We just went through this big valley, but we didn’t see a creek,” says Graul, who heads the district’s stewardship department. They dropped back down for a closer look, and that’s when they started spotting the sinkholes studding the meadow, eroding away to reveal buried debris and rusting rings of corrugated aluminum channeling a steady trickle of water. “We realized that there used to be a creek all through this valley,” Graul says, “but it was in a culvert now.” Graul would come to learn that throughout the 20th century the property’s previous owners had laid more than half a mile of culverts to contain the streams that drain into upper San Leandro Creek. Then they buried the culverts and filled in the creek channels with dirt and debris, creating a level, gently sloping field that offered little clue as to the land’s original topography or ecology.

Graul says that first visit sparked what would become the most ambitious stream restoration in the park district’s 90-year history. Following three years of construction, later this year the public will be welcomed back to a landscape transformed. Streams are once again coursing down valley, bordered by nascent willows, alders, oaks, and lupine. The creeks have new names, too: the main stem is Alder Creek, and a steep side drainage is now Leatherwood Creek. More than five miles of new or revamped trails for hikers, bikers, and horseback riders cross the property.

Since 2020, crews have dug up 30,000 cubic yards of fill dirt and debris and pulled out 2,900 linear feet of culverts. The practice of excavating once-buried creeks is known as daylighting, and Graul reckons this is one of the biggest such projects the Bay Area has ever seen. “At least four acres of riparian habitat have been added to this park,” he says. “Just on that scale alone, that makes it extremely exciting, and one of the best projects I’ve ever worked on.”

Tunnel vision

The park district was motivated to restore Alder and Leatherwood Creeks in part to make the place safer, says Carmen Erasmus, a landscape architect with the park district who’s overseen construction. “By the time we got the property, [the culverts] were failing, and some areas had huge subsidence because it wasn’t engineered fill, so it just was collapsing,” she says. Every year, park district staff noticed new or bigger sinkholes and more erosion throughout the valley.

Aside from the safety hazards, culverts cause a cascade of problems for plants, animals, and ecosystems, explains Scott Stoller, a civil engineer with the park district. Water runs through a pipe a lot faster than it does over the mud, rocks, and pools of a natural streambed, so culverts can raise the risk of flash flooding downstream during big storms. They also sever streams from the hydrology of the surrounding landscape: “Sometimes you’ll find that natural creeks get shallow groundwater contributed from the surrounding area, and sometimes creeks are able to recharge the groundwater table,” Stoller says. A culverted creek, by contrast, might run dry earlier in the year, or the surrounding landscape might be deprived of groundwater that feeds seeps and springs.

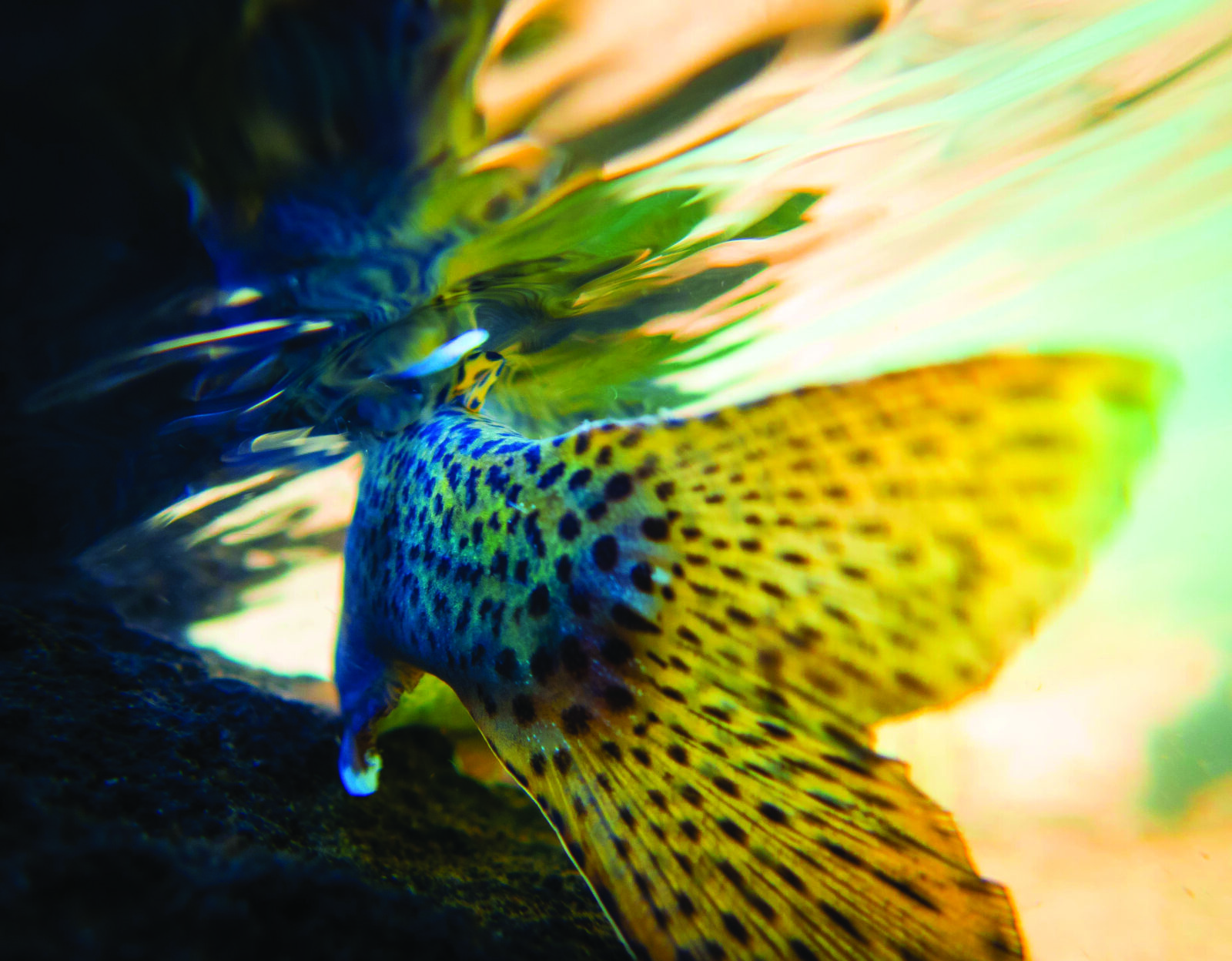

The rocks, gravel, and mud that make up the bed of a free-flowing stream are home to all kinds of bugs, snails, and algae. These tiny critters and plants form the base of the local food web, Stoller says, while abundant streamside vegetation provides habitat for bugs, fish, birds, and mammals. So when creeks disappear into culverts, the consequences for plants and wildlife radiate outward, far beyond the streambed.

“Riparian habitats are just very important to maintain the ecology of the whole region,” Graul says. Of course restoring these creeks creates new terrain for aquatic species like fish and frogs, “but we’re also talking about a lot of habitat for migratory songbirds and native riparian birds … It’s something we’re really proud of, to be able to establish this much habitat in a region that has limited opportunities for this scale of restoration.”

Welcoming rainbow trout

Erasmus shows me around the project in March, on a rare sunny day sandwiched between two of this winter’s big rainstorms. We park outside the locked gate at Eastport Staging Area (formerly known as Wilcox Staging Area) off Pinehurst Road, a mile outside the tiny village of Canyon. (The park district opened the property to the public for a few years once the transfer from private ownership was complete, but it’s been closed since construction began in 2020.) My tour begins just below the property, where Alder Creek flows through a giant culvert under Pinehurst Road and over a rocky waterfall into San Leandro Creek. The rocks are new, Erasmus says: before construction, the culvert’s mouth hung out over a sheer five-foot drop.

Until recently, this culvert was the first hurdle facing rainbow trout that swam up San Leandro Creek each winter, looking for suitable spawning grounds in Alder Creek. Most trout couldn’t clear the jump into the culvert, and if they did, they’d struggle for purchase on the slick metal floor and get flushed right back out. But every winter, Graul says, a few trout somehow managed to run this gauntlet—where they’d promptly get stuck at the mouth of another culvert.

In general, introduced rainbow trout populations are holding steady across the country, where they’re commonly stocked for sportfishing. But San Leandro Creek is part of the species’ “home range,” Graul says—the fish is native to the west coast of North America—and here their populations are perennially squeezed by habitat loss and drought. “We thought, if we just built a stream for them, the trout would come, and they could get up into the upper areas of the watershed for spawning,” Graul says.

Though the culvert under Pinehurst Road is outside the park district’s jurisdiction, its crews made some upgrades here to make it easier for rainbow trout to get up into Alder Creek. They piled up rocks in San Leandro Creek at the culvert’s mouth, giving the trout a sort of ramp to swim up in place of the previous drop-off, and added offset blocks to the culvert’s floor. These “fish baffles” give trout better grip and the chance to take short rests on their trip through the pipe.

Erasmus and I cross Pinehurst Road onto the McCosker parcel and walk up a gravel track along the newly daylighted Alder Creek. Rolls of jute and soil line the banks, studded with leggy oak, willow, and alder saplings. A few hundred feet up from the gate, Leatherwood Creek tumbles down the hillside across from us. This stream was also buried (and officially nameless) when the park district acquired the property. Now it courses over rocks and gravel on its short, steep journey to its confluence with Alder Creek. Erasmus points out a log in the channel, remnant of a tree that crews had to remove to reshape the creek bed, and which they left in the stream to slow the flow and create pools and eddies.

“These are elements that help create channel complexity and help naturalize the channel,” says Stoller of the rocks, gravel, and logs that crews have arranged in the creek bed. “The goal is to create the conditions that help a natural ecosystem recover.” Once construction is complete and the streamside vegetation has had a few years to grow in, this property should provide habitat for 12 special-status wildlife species, including California red-legged frogs, golden eagles, Cooper’s hawks, Alameda whipsnakes, and San Francisco dusky-footed woodrats.

As we walk farther up into the property, the excavated channel grows deeper and wider. I start to appreciate just how much dirt crews had to move to rebuild the valley’s original topography—and relatedly, how drastically the fate, and shape, of the land has changed in the past 150 years.

Times change

In the 1950s, this valley was owned by Alfred McCosker, a descendant of one of the first white families to establish a ranch in Canyon back in the 1860s. The McCoskers were builders; Alfred’s brother John was basically the Forrest Gump of Bay Area infrastructure projects. According to an interview his daughter gave in 2019, John McCosker helped build the Golden Gate Bridge, the Bay Bridge, the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge, and the Benicia Bridge. He also pitched in on the Caldecott Tunnel on Highway 24 between Oakland and Orinda, the Robin Williams Tunnel on Highway 101 in Marin County, the Webster Tunnel connecting Oakland and Alameda, the Berkeley Pier, and the Oakland Coliseum.

In the 1950s, the McCoskers launched a quarry and rock-crushing outfit on their land along Alder Creek to supply material for the postwar building boom that saw freeways and suburbs expand deeper into the East Bay Hills. To make space for their trucks and equipment in the narrow canyon, they laid down a mismatched assortment of culverts and filled in the valley floor with dirt and debris, up to 30 feet deep in places, until they’d fashioned themselves 250 acres of industrially useful space.

The quarry and rock-crushing business shut down in the 1970s. In the 2000s, Alfred’s descendants sold the parcel to a real estate developer as part of a mitigation deal for a planned thousand-acre subdivision and golf course in Orinda’s Gateway Valley. Environmental groups, including the Golden Gate Audubon Society and the residents group Save Open Space–Gateway Valley, objected to the development: the valley, a pocket of streams, wetlands, and oak woodlands extending southeast from the Caldecott Tunnel, provided safe passage for wildlife between the San Pablo Creek Watershed and Tilden Regional Park to the north and the San Leandro Creek Watershed, Redwood Regional Park, and Las Trampas Regional Park to the south. Through decades of negotiations, the development—now known as Wilder—was eventually whittled down to 230 acres, and 1,300 acres between Orinda and Oakland were set aside as open space. The developer donated the McCoskers’ land to EBRPD in 2010, and the park district plans to accept the donation of an adjacent 390-acre parcel known as the Western Hills Open Space in the coming years. Together, the two properties will nearly double the size of Sibley Preserve.

The Alder Creek project cost $16 million. It received $10 million in grants from the Environmental Protection Agency, California State Parks, the Wildlife Conservation Board, the California Department of Transportation, the California Coastal Conservancy, and the California Natural Resources Agency. Private donations added another $500,000. Park district funding, mostly from Measure WW, accounted for $5.5 million.

Construction on the Alder and Leatherwood Creeks restoration is on track to wrap up later this year, but more transformations are slated for the years to come. Between the McCosker and Western Hills additions, the park district plans to add four miles of existing ranch roads and four miles of newly built single-track to Sibley. It’s also planning to add parking spaces, toilets, and water fountains to the McCosker property, along with a picnic area and a group campground.

Alder Creek flows where the former culvert lay. Right: The view from the ridgeline above the restoration. (Photos by Carmen Erasmus (2x)

The first big test

This past winter, with its seemingly endless parade of big rainstorms, has served as a test of the project’s resilience, with promising results. The storms have smashed rainfall records, washed away roads and homes, swamped farm fields, and blown down countless trees throughout the state. But on the day I visited, Alder and Leatherwood Creeks were running high yet mostly clear, and roads and trails around the property were damp but intact. “We were nervous we’d uncover some flaws with the design, but we haven’t seen any excessive bank erosion or any failures of parts of channels we’ve engineered,” Graul says. That’s good news for the area’s plants, animals, and fish and for people who are eager to come check this new place out. And less erosion on Alder and Leatherwood Creeks means cleaner water flowing into San Leandro Creek, which empties into a reservoir that makes up part of the drinking water supply for 1.4 million East Bay Municipal Utility District customers.

The whole landscape has been “behaving beautifully through high flows,” Graul says. “It’s held up and operated like a natural stream system would operate.”