On a hot July day, I sat in the generous shade of an old western sycamore to eat my lunch, and the tree seemed to quietly speak. A warm breeze made a leathery susurrus of leaves against one another and the tree’s branches. The sycamore’s bark was smooth against my skin. I ate leisurely, listening. The air smelled a little sweet, and dry with summer dust. After a time I walked on again, slow in the midday heat, wending my way along the trails in Livermore’s Sycamore Grove Park through golden oak woodland and the now-rare habitat known as sycamore alluvial woodland. Grand old sycamores grew well-spaced amid flat grassland on either side of two stream corridors. I took a detour along the narrow, dusty Olivina Trail to put my feet in the Arroyo del Valle’s cold water. The stones below my sandals were smooth and tawny, the gravel bars shaded here and there by silvery willows and fast-growing mule fat.

Such wide, graveled banks are a classic feature of sycamore alluvial woodland, and they’re integral to the trees’ health and longevity. A distinct and vital ecosystem in California, sycamore alluvial woodland is characterized by summer-dry streambeds that branch and braid out through the sandbars, silt, and gravel beds deposited by winter rains and floods. (My feet cooled in water that fills the arroyo year-round now, managed by the Del Valle Dam for agricultural purposes.) Livermore’s Sycamore Grove Park is among the few preserved alluvial woodlands left in the East Bay, and as such it provides us a window into an older California.

Before heading back to the Arroyo del Valle Regional Trail, I stopped on the Olivina Trail to visit an old sycamore known to park personnel and visitors as “the hobbit tree.” It’s not hard to see why—from the outside, the tree resembles a fantastical teapot with a window, and what’s more, it’s partially hollow, with an arching doorway that opens into the tree’s interior. Someone placed a stump just inside, and I sat there for a long time, looking up into the sycamore’s hollow trunk, into darkness, trying to imagine the life of such a tree, roots down in the alluvial gravel of the old Arroyo del Valle, tall branches clattering in the breeze and home to countless birds, insects, and mammals.

I and the arroyo are one, a single motion of water and wood. I and the arroyo and the kingfisher know the same old words. My roots touch cold underworlds; they sing of ancient winter floods and long summers dancing in full leaf.

BARK

Something about the way sycamores grow, the places in which they thrive, the way the wind moves them, the quality of their shade—all of this has captured the human imagination for millennia. There are 11 officially recognized sycamore species—known more commonly as plane trees, part of the Platanus genus—in the world; the western sycamore (Platanus racemosa) is native to California and Baja California. It is said that in ancient times an image of Dionysus, god of green life among the ancient Greeks, was found inside a fallen sycamore tree beside the Meander River, which was left split in half after a storm. And to Xerxes, the famous Persian king who marched across Asia Minor to conquer mainland Greece in the fourth century BCE, the sycamore’s curving form and substantial canopy inspired an almost feverish devotion. Herodotus was first to tell the story—how Xerxes was waylaid for a day and night by the sight and luxurious shade of a sycamore tree, and that later he had the tree’s likeness cast on a medal of gold, so that he could always carry its form with him.

By all accounts he was ridiculed for this seemingly strange behavior, but perhaps the historians who wrote about him did not consider how welcome the broad shade of a sycamore would be after a long march. Nor indeed the impression a very large specimen can make upon the senses. For there is something hauntingly human about a sycamore’s smooth, skin-like bark, about the voluptuous curves these trees often develop at the waist and roots as they age. Some resemble elephant legs; others remind me of melted candles the size of titans; now and then very old individuals look strikingly like broad-hipped women with two or more pendulous breasts. These seeming breasts are in fact burls, round protuberances whose cause is unknown. In the Barbareño and Ventureño languages spoken by the Chumash from central and southern California, the word for sycamore and the word for wooden bowl—khsho’—are the same, because the trees were so prized for their beautiful round burls, which were carved into lightweight and lovely vessels. Trees are rarely harmed by burls, and they can continue to transport water and nutrients through the twisted skin and onward throughout their trunks and branches. The sycamores in the park are more vulnerable to a fungal disease known as anthracnose, which causes leaf spotting and deformation, cankers, sudden leaf drop or twig dieback.

In Lydia, they say, he saw a large specimen of a plane tree, and stopped for that day without any need. He made the wilderness around the tree his camp, and attached to it expensive ornaments, paying homage to the branches with necklaces and bracelets. He left a caretaker for it, like a guard to provide security, as if it were a woman he loved.

—Aelian, 3rd century AD

In July the shade under the park’s generous-armed sycamores is a relief. Not only is their shade cool and dense and the warm breeze in the leaves a kind of hymn; their bark is cool too. This is because it is quite thin and is constantly exfoliating throughout the year. Scientists and arborists are not quite sure why, but they theorize that thin-barked trees like sycamores exfoliate in order to rid themselves of harmful pests that thicker bark would keep out. Others postulate that the bark beneath freshly shed skin can photosynthesize, even after leaves have dropped. This allows a longer growing season for a tree that is adapted to hot weather and intermittent water.

WIND

Two wild turkey mothers eyed me warily, herding their ungainly poults into the coyote brush with quiet clucks as I walked farther down the Arroyo del Valle Regional Trail, toward an old almond orchard and a loop along the edge of the historic Olivina Winery. All around me, the high summer winds made the sycamores sing across the alluvial plain. To the right, a straight road lined with walnut trees stirred, dark green. It was a hot wind, full-bodied as the wines from nearby vineyards. The smell of dry oat grass and warm stones, California dust, and the faint syrupiness of slow water in the streambed—all of this came on that summer wind and swung the sycamore leaves into words, a tender, round murmur. It was the strong, warm wind of summer afternoons in the Bay Area that builds as the hot inland temperatures along the Central Valley pull the chilled air rising off the vernal Pacific’s cold-water upwelling through the Golden Gate and east. Hot air rises, and as the saying goes, nature abhors a vacuum, so the colder air off the summer ocean is forever rushing inland as the coast cools in the afternoon.

It seems to me that in every season sycamore trees speak differently. In autumn as the powerful summer winds soften, the trees’ leaves fall gently, like great bronze hands across the ground, making a dry hush. As a girl I saw their relatives on the eponymous Sycamore Avenue in Mill Valley as the first sure sign of fall. I loved to leap through the leaf piles; I would pick my route down the street based on where they had fallen, most often in the gutters. I loved the sound of their crackling underfoot. The dry sweet smell of those dead leaves is all tied up in my memory with the first rain and the first cold nights near Halloween. At Sycamore Grove Park, the wild autumn sycamores will surely welcome the coming rains and the hopeful possibility of floods, when their round, softly spiked seedpods will be carried off downstream. Then the brisk winter winds will call forth the harsher clack and rattle of bare twigs and branches, singing a kind of underworld song.

WATER

The body of the western sycamore is an expression of the way water runs over and under the earth, of flood and scour, of deep groundwater and summer drought, of the true nature of old California’s rivers and creeks.

Although once widespread, only 2,000 acres of extant sycamore alluvial woodland have been mapped by biologists in all of California; this is a habitat uniquely adapted to the hydraulic patterns of the Old West, and as such it has suffered significantly over the last 200 years. Sycamores thrive on a good December inundation—the kind of winter rain that comes maybe once every decade. Such flooding replenishes groundwater, helps carry fresh alluvial sediment and silt to new areas along with the sycamore’s own seeds, which often germinate after the ground is cleared by such floods. Sycamores need these winter floods to flourish and to grow healthy seedlings; there’s no other way around it. They need freed rivers, uninhibited streams that swell and recede in their own and ancient manner.

Arroyo del Valle runs through the middle of Sycamore Grove Park, a single-channel stream still rich with willows, red dragonflies, and omnipresent kingfishers whose calls can be heard ringing far through the trees. Once, the Arroyo del Valle was a braided network of smaller creeks that carried water deeper into the sycamore woodland, with more sandbars and gravel beds throughout. But in 1968 the arroyo was redirected into Del Valle Dam, which releases water steadily and without much variation all year round throughout Livermore’s agricultural lands. The arroyo’s management is a microcosm for the control of rivers, streams, and groundwater that has altered California’s landscapes. “Most of [California] is relatively dry, and its rivers are like the fingers of beneficent gods to the farmers living here,” wrote Elna Bakker in her classic An Island Called California. “These streams ensure an underground water supply from artesian wells, and impounded behind dams they become power and water resources without parallel.”

When I imagine the California of old, I see the endless tule channels of the Delta, winter floods so big they turned half the Sacramento Valley to a lake, riparian corridors dense and fecund with summer green and wild with winter rains, unbridled, unmanaged, unpredictable, sometimes flowing in single carved channels, other times meandering in lazy snaking bends. Never wholly fixed. Something like this 1850 description of the sycamore woodlands around the South Bay’s Pajaro River, by author Brayard Taylor:

The meadows were still green, and the belts of stately sycamore had not yet shed a leaf. I hailed the beautiful valley with pleasure, although its soil was more parched and arid than when I passed before, and the wild oats on the mountains rolled no longer in waves of gold. […] As we journeyed down the valley, flocks of wild geese and brandt, cleaving the air with their arrow-shaped lines, descended to their roost in the meadows. On their favorite grounds, near the head of Pajaro River, they congregated to the number of millions […].

But water is gold in California, where summer drought is the norm, and if you control the water, you hold the power. Such plains as those around the Pajaro River have been long since transformed. Wherever you see vast tracts of agriculture—the historic vineyards of Livermore just the other side of the boundary at Sycamore Grove Park, the Central Valley’s endless fields, the historic fruit orchards of Santa Clara—you are looking at the transmutation of old floodlands and rich groundwater into crops.

After Del Valle Dam was built, the health of Livermore’s sycamore woodlands declined significantly. The dramatic flood events that happened once every 10 to 20 years vanished entirely. At capacity, roughly 77,000 acre-feet of water are held behind the dam’s great concrete walls, a boon for modern agricultural irrigation and municipal water distribution, but a death knell for sycamore trees in the old alluvial woodlands. The drought years from 1987 to 1992 further damaged Sycamore Grove’s trees. But it wasn’t just the drought that damaged the trees; for years water was pumped through the highly managed creek beds. Sycamores that adjust to summer water never grow deep roots that reach down to the groundwater. When drought struck, the trees in the park were unable to access the aquifers deep below the gravel beds.

Those growing right along the Arroyo del Valle creek were most heavily damaged, and healthy seedlings have been slow to regenerate naturally. But rangers and scientists are working together to manage water flow from the dam to more closely mimic the ebb and flood that sycamores prefer. Seedlings are being planted as well, protected carefully in little wire cages, and anthracnose-infected leaf litter is routinely cleared.

“We’ve seen almost no young trees come up on their own in the last 20 years,” says Amy Wolitzer, one of Sycamore Grove Park’s most devoted rangers. And then in the 2016-17 winter, thanks to historic rains, Arroyo del Valle underwent massive flooding, the most significant inundation since 1997. “The weeks of water flow washed out a lot of silt and plants that have built up over the last 20 years and returned the streambed to the exposed gravels I remember from when I was a kid,” Wolitzer says. “Hopefully this cleared out the anthracnose and will help our sycamores thrive and maybe allow for new seedlings to germinate.”

MENAGERIE

A thriving expanse of sycamore woodland is truly something to behold, to celebrate, protect, and sustain. Walking through Sycamore Grove Park with a breeze in the treetops and acorn woodpecker families calling from atop snags, you can for an afternoon imagine an older California. Many trees here are more than a hundred years old by now, and they grow in ancestral rings, with small shoots sprouting up from a central old trunk until eventually the “mother” tree hollows and dies and the youngsters each grow into their own sinuous height. Though individuals may fall, the root systems beneath the ground that sustain these sycamore families are thousands of years old, Wolitzer says. Single trees can live as long as 500 years; the oldest sycamore in the park, dating back almost 300 years, was a seedling before the Spanish arrived in 1776. Such aged giants provide home and sustenance for a menagerie of animals. Once, monarch butterflies overwintered in sycamore branches in great numbers, and bat colonies roosted in the caverns. In the 1920s, one naturalist observed 41 great blue heron nests and 28 night heron nests in a single 7-foot-wide sycamore—a veritable village!

Inchworms, wood-boring beetles, lizards, snakes, squirrels, and barn owls will all take refuge in the hollows and heights of an old tree; acorn woodpeckers use dead limbs for nesting and granaries, and just this spring a red-shouldered hawk family raised three chicks in a grand and messy stick nest high up in the sycamore branches that shade the park’s native plant garden. Black-tailed deer happily bed down in the golden grass beneath the sycamore canopy on a hot day; when I visited the park I watched a doe startled from just such a nap by passing walkers. Gray foxes, consummate climbers, may scramble up the smooth cool trunks to snooze in a comfortable crook, leaving behind a telltale scat.

These trees carry worlds in their wildly curving arms, their dark roots and hollows, and voices in their wind-sung leaves. What the western sycamore carries of an older California should not be underestimated, nor forgotten. Walk among them quietly, listening, and you will begin to hear their singular song.

GETTING THERE

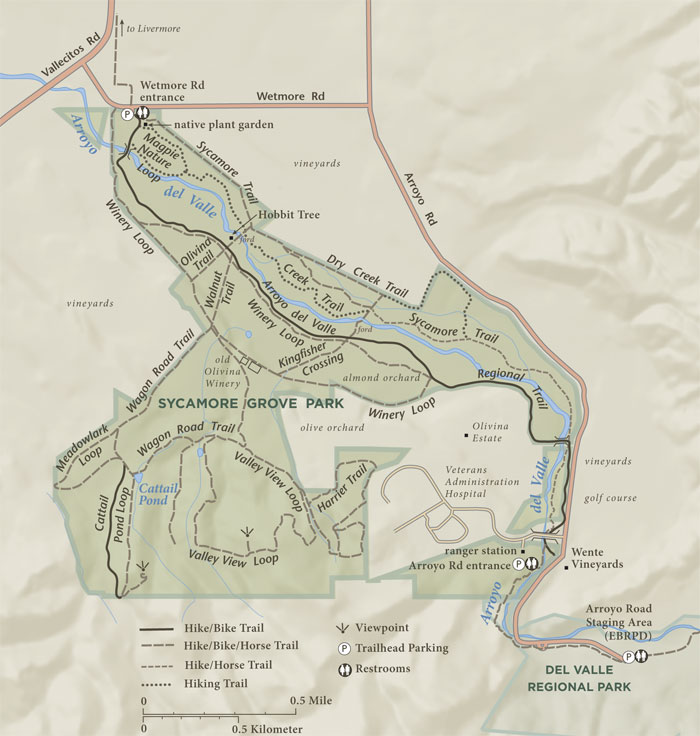

The park is just 5 miles south of downtown Livermore, with entrances at the two ends of the park—Wetmore Road (north) and Arroyo Road (south). There’s a $7 parking fee (you will need exact change) and picnic tables and bathrooms at the entrances. Horses, bikes, and leashed dogs are welcome. Visit the park website for more.

FAVORITE TRAILS

- For a lovely, child-friendly walk, take a left on the Olivina Trail from the Arroyo del Valle Regional Trail and visit the hobbit tree. Just down from the tree you can cross the creek (or play in the water), then wander back along the Creek Trail to the Magpie Trail through open sycamore-dotted grasslands. (Roughly 1 mile round trip.)

- For a more strenuous hike, follow the Winery Trail along the vineyard fence line, past hundred-year-old olive trees from the Olivina Estate, to the Wagon Road Trail and the Valley View Trail, which will take you on a loop up into the hills overlooking the sycamore alluvial plain and greater Livermore. Visit the observation deck by Cattail Pond to look for dragonflies, western pond turtles, and waterbirds. (2 to 4 miles round trip, depending on route.)

BLOOMS & GARDEN

The park supports a rich array of wildflowers, and park volunteer Wally Wood created an extensive digital guide that lists the species, their bloom times, and habitats. There’s also a native plant garden just past the northern entrance with four areas:

- Ohlone Section features plants important to Livermore’s indigenous inhabitants, such as yampah, elderberry, red bud, toyon, wild rose and willow.

- Butterfly Section for native pollinators.

- Grassland Area to help foster iconic perennial grasses, such as purple needlegrass and june grass.

- Sensory Section with sweet, resinous, and tactile plants, such as pearly everlasting, sticky monkeyflower, and black sage.

CONSERVATION & RESEARCH

- Sycamore Grove Park is part of the Livermore Area Recreation and Park District, and is owned by the LARPD Foundation, a community non-profit. Volunteering opportunities in the park are offered through the LARPD, and local Girl Scouts have helped with native plant garden work, trail maintenance, species guides, and more.

- In April 2017, the LARPD partnered with the Volunteers for Outdoor California to begin creating 1.1 miles of new trail in the park. Called the Harrier Trail after the beautiful raptor so often spotted nearby, the trail will connect with the existing Valley View Loop.

- Biologists with the San Francisco Estuary Institute are hard at work running field experiments and collecting data to help protect and restore sycamore alluvial woodlands throughout the greater Bay Area.