From blockbuster movies to onesie pajamas, great white sharks have become so kitsch that even the word “shark” has become practically a synonym for this one species. Take the Bay’s local hockey team, the generically named “Sharks,” which – as you can see in their stick-crushing logo and arena projection of great whites swimming on ice — has only one species in mind.

Tonight, @ErikKarlsson65 goes swimming with the @SanJoseSharks. 🦈 pic.twitter.com/q04RgpEY8a

— NHL on NBC (@NHLonNBCSports) October 3, 2018

Sure, the infamy of great whites is rooted in one of humanities’ primal fears — being eaten alive. Sure, the fear is not unfounded. As the largest macro-predatory shark in the world (the biggest being planktivores), great whites target prey of comparable size to humans. Nevertheless, human fatalities by great whites, or any shark for that matter, are incredibly rare. Perhaps this infrequency is the reason why the public’s fear of great whites has morphed over time into fascination and heavy anthropomorphizing.

Meanwhile, the great white’s gluttony for the spotlight isn’t entirely fair. October is generally the peak season for a variety of coastal sharks, not only in California, but in Hawaii and the United States East Coast as well. All these places have dubbed the month “Sharktober” and celebrate with social media themed outreach and in-person events. To my surprise these, too, tend to focus on the great white.

There are more than 550 extant species of sharks (and counting), categorized into eight different taxonomic orders. The continual use of one species as the archetype is a little fishy. Ultimately, the narcissism evoked by a name like great white shark becomes even more fitting.

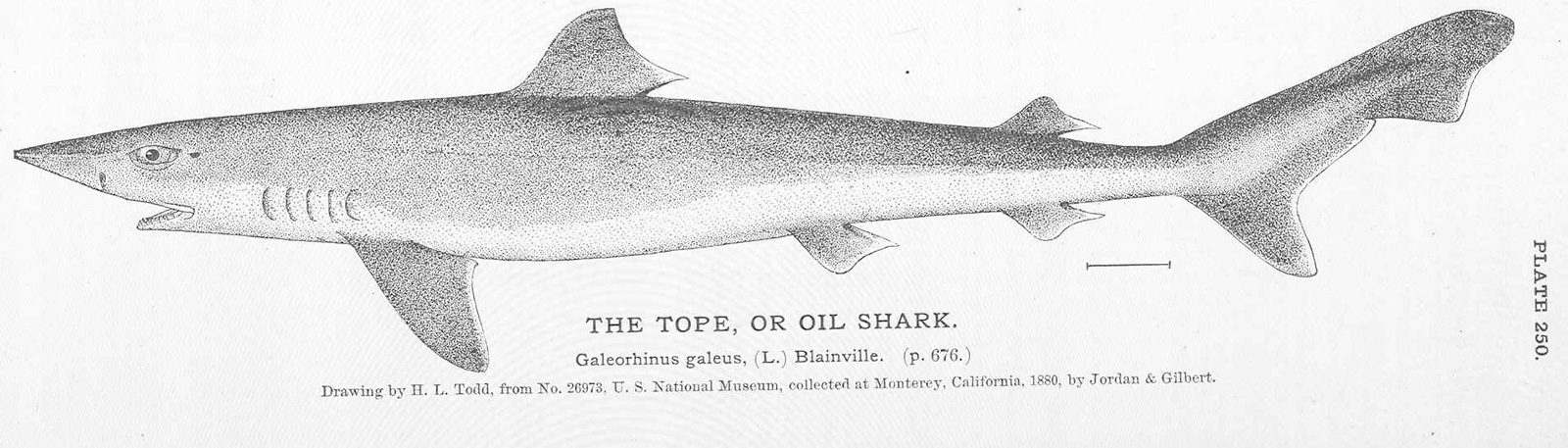

The shark I study most, Galeorhinus galeus, has a few names of its own. Australians know them as school sharks; in Canada they’re topes. In the San Francisco Bay Area we call these medium-sized coastal sharks soupfins. Supposedly, the “soupfin” common name originates with San Francisco’s Chinese settlers, who preferred eating this shark. Globally, the shark fin soup industry has devastated many elasmobranch species (sharks and their relatives). Surprisingly given the name, for soupfins this was not the case. Instead, it was the mid-twentieth century disruption of Europe’s vitamin A industry that pushed the soupfin fishery into unsustainability.

In the 1930s, vitamin A was extracted from the oily livers of cod fish, but the chaos of World War II curtailed European exports. Since the oily livers of sharks take up one-third of their inner body cavity, sharks could serve as a replacement for cod liver. Among shark species, soupfin sharks have one of the oiliest livers, thereby making them the principal target of the vitamin A fishery. During this intense fishing pressure, another common name for the shark was born: the vitamin shark.

A century ago soupfin sharks were the most abundant shark in the San Francisco Bay (and great white sharks were an afterthought). But the market value of soupfin jumped from $50 per ton to an incredible $2,000 per ton in the 1940s. The California Department of Fish & Wildlife (CDFW; at the time called Fish & Game) started to study soupfins and monitor catch rates. By 1944, more than 24 million pounds of soupfin shark had been landed in California in less than a decade. Nearly 40 percent of the landings came from San Francisco Bay. Like a rollercoaster slowly creeping up to the ultimate pinnacle, CDFW was the one person on the ride trying to avoid that unavoidable downhill. Yet before management plans could be created, the fishery simply… stopped. The ride was unceremoniously over. In 1947 the vitamin A industry, like a child abandoning old toys for new ones, lost interest in sharks due to the discovery of synthetic vitamins. With major fishing over, no one ever bothered to assess California’s soupfin fishery or label it a bust, even though circumstantial evidence strongly suggested that it had collapsed.

The soupfins do not seem to have returned. Today the most abundant shark in the Bay is the leopard shark. And despite the long, intertwined history of soupfins and San Francisco Bay, the shark’s story is unknown to many current Bay Area residents.

Perhaps this is also because as the soupfin fishery stopped, right on cue, great white sharks took center stage in California. The 1950s saw 11 unprovoked shark attacks in California, the most attacks on swimmers, waders, and divers in a decade according to 90 years of record-keeping by the University of Florida’s International Shark Attack File. In the heart of San Francisco Bay, rumors flew that a prison break at Alcatraz had ended in the jaws of great whites. By the time the movie Jaws came around in 1975, the face of shark research had changed. It’s often said that science knows little about great whites, and it’s somewhat true, but the truth is we know even less about sharks like soupfins. Research on California’s great white sharks has revealed migration patterns, unique physiological traits, and recently the first known nursery. By contrast, the most current knowledge we have of California’s soupfins was collected nearly 70 years ago and our questions as scientists abound.

For example: the San Francisco Bay was commonly referred to as a nursery for soupfins yet there are no current reports of pups. Was it a nursery in the past but no longer? Landing records show a consistent pattern in which female catches occur in the southern region of the soupfin’s range while males are found in the north. Why? Even more bizarre and equally fascinating, the San Francisco Bay is the only place with reports of both sexes occurring. Is this an error? The global status of soupfin sharks, as assessed by the IUCN, lists them as vulnerable with two sub-populations listed as critically endangered. Surprisingly, the forgotten soupfins of California belong to the only sub-population listed as “Least Concern.” How did this happen?

At the Pacific Shark Research Center (PSRC), where I am a graduate student in the lab of Dr. David Ebert, I want to solve these puzzles. But conducting research on soupfin shark behavior in San Francisco Bay is incredibly challenging. As the largest estuary on the United States West Coast, the size is daunting all on its own. But it’s not the biggest hurdle. Fast tidal currents and near zero visibility make traditional research methods (like the ones conducted in the tropics) ineffective. Without the option to dive or use stationary cameras on the seafloor, our project is using one of the Bay’s biggest assets — the tech industry.

I will be working with Open ROV, a local company that’s trying to overcome the challenges of aquatic exploration with a new device, the Trident, equipped with tiny sensors to collect environmental data and an advanced camera system designed for murky conditions, such as clouded water from plankton blooms or disturbed sediment. The data can be used to better predict where and when soupfins are in the Bay. The greatest challenge, though, is simply finding the sharks.

To expand knowledge of soupfin sharks past their October visits to the Bay, I am also trying to work with water users, including outdoor educators, fisherman, and sailors, so they can make accurate identifications and inform me of any encounters with soupfin sharks. By the end of this work, I not only intend to increase our scientific knowledge of soupfin sharks, but to also reconnect people with one of the authentic mascots of the Bay Area.

-300x221.jpg)