Update August 12, 2017: Hunt for San Francisco Bay Shark Killer Zeroes in on a Suspect

Hundreds of leopard sharks and bat rays have washed up dead or dying on the San Francisco Bay shoreline this spring, the second year in a row of mass elasmobranch death in the Bay and the third major die-off in the last six years. But for the first time since an unusual shark stranding was first reported in the East Bay a half-century ago, scientists say they’re close to an explanation.

“I look at it as a 50-year-old shark murder mystery, and we are hopefully closing in on the killer,” said California Department of Fish and Wildlife senior fish pathologist Mark Okihiro, who has led the stranding investigation.

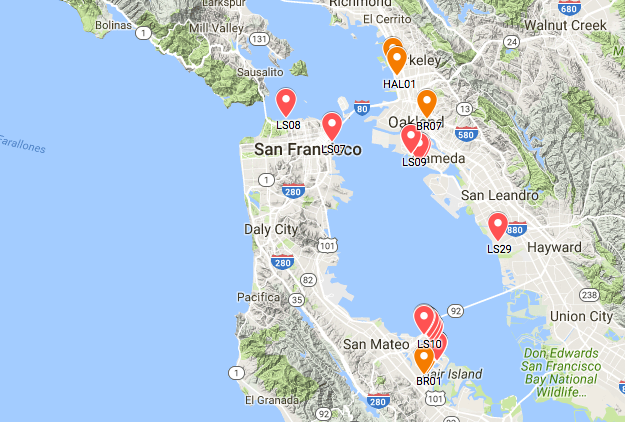

The 2017 die-off started in mid-March and has been concentrated around Foster City and Redwood City, with additional reports from Hayward, Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco. Okihiro, who is based in Southern California, hiked five miles of shoreline around Foster City in the last week of April and found 24 dead or dying leopard sharks and two dead rays. The event is ongoing and appears to be “heating up some,” he wrote in an email this week.

“It’s the dead shark capital of California,” said Sean Van Sommeran, the executive director of the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation (PSRF) in Monterey, which tracks strandings. “It’s major major major.”

Shark die-offs have occurred in the Bay going back to at least 1967, when then-East Bay Regional Park District naturalist Ron Russo reported the deaths of more than 725 sharks and rays on the Alameda shoreline over two summer months. More recently, Van Sommeran says, there were big die-offs reported in the South Bay between 2002-2006. The next major event came in spring 2011, when PSRF tracked several dozen deaths in Foster City, San Mateo, Sausalito and Mill Valley. The timing of the most recent outbreaks offers a clue to the cause, Okihiro said: leopard sharks come together to spawn in shallow water in the spring and early summer, exposing them to more toxins than they’d see in the deeper parts of the Bay where they spend most of the rest of the year.

The problem, though, has been in figuring out exactly where and when the die-offs were happening, the necessary first step to figuring out why they were happening. “No one’s looking at it consistently,” Okihiro said. “It’s not like we could plot out, there were 2,000 leopard sharks that died in 2011 versus 250 in 2012. There is no one with the job of tabulating leopard shark and bat ray death. We’re doing this all on the fly, on a shoestring.”

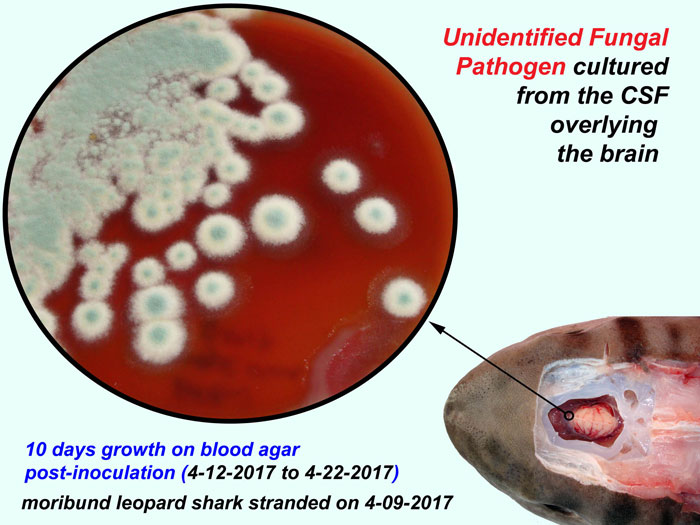

In 2016, Van Sommeran said, a new die-off caught researchers off-guard. This year Van Sommeran’s PSRF team caught wind of the strandings as they started, and so were able to map them as they happened and ship fresh sharks to Okihiro to examine. Okihiro performed necropsies on 26 sharks in April, including what he labeled the “patient zero” for this die-off, a leopard shark recovered from a beach near the San Francisco Airport by a California Fish and Wildlife warden on April 9. That shark, and another one collected a few days later, had signs of a brain infection that had caused them to become disoriented and swim onto shore. So did seven more sharks that Okihiro necropsied after his shoreline walk in late April.

With meningitis established as a cause of death, Okihiro next took samples from tissues and fluid around the sharks’ brains, and isolated a set of still-unidentified fungal pathogens that he thinks infected and killed them.

How the pathogens might have made it into the sharks’ brains in the first place says a lot about the complicated modern Bay. Two centuries of development and fill means that most of the flow of water along the bayshore is controlled — in flood control channels, managed wildlife ponds, and man-made lagoons like the ones surrounding the houses in Foster City. That often stagnant water has become, Okihiro said, like a “giant broth culture” for fungi, and when the water conditions are right the fungal pathogens go nuts and “explode into billions of infective particles in the water column.” Big rain events then push a toxic plume of pathogens out into the wider Bay — just as large groups of the sharks are coming into shallow water to spawn.

The pathogens, Okihiro said, seem to enter through the sharks’ ears or nose, and then travel up a set of ducts into the brain — a pathway recently uncovered by Long Beach State shark biologist Chris Lowe.

Van Sommeran said he thinks the sharks and rays are also harmed by poorly designed tidal gates around the Bay, which were built to control the flow of water around urban areas. Particularly in Redwood Shores and Foster City, he said, tidal gates close in anticipation of rain (to keep tide water out so ponds and canals can absorb runoff rainwater and houses don’t flood) — but in doing so, they can trap sharks and rays in stagnant and increasingly toxic water. “It’s like a tourniquet,” Van Sommeran said. “The pH gets off, dissolved oxygen diminishes, temperature and salinity skyrocket and the sharks begin to die within a day or two. Then when the backwash of urban and suburban runoff fills in, it’s just nasty. The sharks are getting all kinds of infections.”

Jared Underwood, a refuge manager at the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, said in an email the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has installed fish screens on its tidal gates in the refuge to avoid trapping animals, and that the refuge has not received any reports of shark or ray strandings this year.

Leopard sharks are the most common shark in the Bay, and are frequently spotted in shallow coastal waters from Baja to southern Oregon. Like many sharks, they’re long-lived and slow-growing, making mass mortality events particularly concerning for shark researchers. “They’re beautiful sharks, they’re kind of a signature species of California and San Francisco Bay in particular,” Van Sommeran said. “Leopard sharks, in the big picture, are vastly diminished from like the 1950s. They used to be typically 5-6 feet long, and common. It’s hard to find one 4 feet long now.”

Strandings probably represent a fraction of the sharks that have actually died, since sharks that die in open water simply sink. Even those that do wash up onto beaches, though, don’t find their way to wildlife officials. Well-intentioned onlookers often try to push sharks back into the water in an attempt to revive them — assuring, Okihiro said, that the shark swims off to die elsewhere. “Everybody wants to save the sharks,” he said. “But we can say with 99.9 percent certainty that the shark is on the beach because it’s infected and dying. Pushing it out to sea just means we don’t get a chance to examine it. We don’t get a chance to know what killed it.”

Strandings also aren’t always reported, Van Sommeran and Okihiro said, but if they are it’s often to The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, which then forwards the calls to PSRF in Monterey. (A TMMC spokesperson confirmed that it forwards the calls, but doesn’t track how many it gets.) Seven weeks into trying to track this year’s die-off, Van Sommeran said he’s stretched thin every volunteer he has and is running on fumes. “I’m down here in Monterey Bay,” Van Sommeran said. “We were responding daily for the first four weeks of it. I’m driving an ‘85 Nissan sedan, but it’s in the shop now. It’s been a disaster.”

If you see a stranded or dying shark anywhere in California, call or text the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s CalTIP hotline. You can also report strandings to the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation. Or take a picture and upload it to iNaturalist, where it can be added to a project tracking leopard sharks and bat rays around the Bay.